Audi’s inbound logistics depends on tight planning and delivery adherence, while the carmaker is also exploring more consolidation within the Volkswagen Group

Audi’s highly complex in-plant strategies have direct impacts on its inbound material transport. “We have more variety, which brings higher frequency to the workplace,” says Dieter Braun. “If you go via the in-house logistics to the inbound logistics, it is the same idea; we have to increase the frequency of transport in a cost-effective manner.”

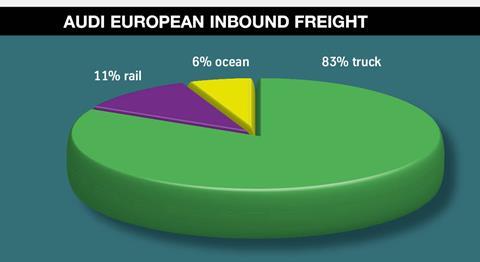

Flexibility is a major requirement of this approach, so Audi’s inbound network is geared toward truck transport. In Europe, around 83% of freight moves by road, 11% by rail and 6% by ocean containers. The rail deliveries come from a number of bulk suppliers, but are dominated by inter-plant movements, such as engines from Gyr and gearboxes from Kassel, as well as other components and bodies in and out of Ingolstadt (where a huge rail station divides the plant). Despite the importance of truck, Hauf notes that inbound rail deliveries have increased in recent years.

The different logistics infrastructures at the plants influence inbound deliveries. For example, Ingolstadt receives some 650 inbound trucks per day and a further 25-30 rail wagon loads of material. About 200 of the trucks check in at the GVZ for the packaging warehouses or supplier sequencing, while the rest deliver directly to the plant gates or trailer yard.

Neckarsulm receives about 480 trucks per day and around 27 train wagons of material. About 160 trucks go through the Heilbronn logistics centre each day, as plant-based automated warehouses allow more direct deliveries to the docks. There are more JIS deliveries from nearby estates and further afield, according to Braun.

Excluding JIS deliveries, direct truckloads from single suppliers make up around 70-80% of inbound logistics for Neckarsulm, as compared to material moved through regional supplier consolidation centres or milkruns, of which there are relatively few. Both plants tend towards direct deliveries because of their product variation, but especially Neckarsulm. “We have very few milkruns because there is a big dynamic in the model mix and it wouldn’t be effective to coordinate two or three suppliers to organise the milkrun,” says Braun.

Audi’s plant logistics teams keep close control on the direct deliveries for each supplier, adjusting frequencies every week based on production demand. According to Braun, delivery frequencies range from once a week to three times per day and are constantly adjusted. “We set out a weekly plan each quarter for direct deliveries, but every week we check if we need to adjust daily shipments,” Braun says.

All incoming trucks are monitored across fixed unloading and loading windows, as well as fixed drop shipment times for suppliers. The current results are good, according to Michael Hauf, with drop shipments in Europe having a truck utilisation of 92%; for the whole network it is 85%. In Neckarsulm, direct deliveries are 91% utilised with a 92% adherence to time windows.

Keeping long distance suppliers on track

Logistics performance for the Neckarsulm plant ranks near the top of the Volkswagen Group’s quality and process standards. One area in which it has taken a particular lead has been in long-distance JIS items, a process known as the ‘pearl chain’. These shipments are based on a six-day, frozen production schedule that helps Audi to programme a stable supply of goods even at long distances.

Neckarsulm started this project in 2002 with the A8, successfully implementing it across the plant by 2010 with 96-97% delivery accuracy. According to Braun, the use of this process has lowered logistics costs and conserved space by eliminating sequencing areas. “For the current A6 and A7, for example, the wiring harness is produced directly in sequence in Romania, more than 1,300km away,” he says. “The sequence is fixed six days before, then the truck delivers it to Neckarsulm, remaining in the trailer yard just one shift before it is unloaded from the truck already in sequence.”

According to Braun, one of the biggest challenges for establishing such deliveries is to change the mindset of those in logistics, particularly for material follow up and disposition logistics. Such managers might be used to checking the status of incoming material and blocking production should supply seem uncertain, but in the pearl chain, the sequence depends on absolutely zero deviation, since the supplies were loaded into trucks in an established sequence. Braun says there should be no doubt that the material will be consumed in the predicted sequence, so the “absolute priority” is to make sure that the needed material will be there at the right time.

The responsible logistics manager can thus rely on the scheduled sequence and concentrate his efforts on the logistics and material flow. “You have to coach him that he can rely 100% on the delivery sequence that has been set in advance, but he has to fight to get the parts needed for today’s sequence,” says Braun. “That is a big change and it takes time.”

Such strengths in one factory can be used to the benefit of the entire network, says Hauf. Experts from Neckarsulm are now training workers for the new factory in San José Chiapa, Mexico, which will adapt features of the pearl chain.

Ingolstadt is also following suit, with a project to stabilise its programming and supplier deliveries. The initiative, known as ‘IN-SPUR’ (which means ‘on track’ in German), aims to increase compliance with scheduled production programmes and adherence to delivery dates. According to Johannes Marschall, the real effort comes in better integrating logistics with Audi’s sales, production and purchasing teams.

“In close cooperation with production, we at Ingolstadt plant logistics are already on a very good course,” Marschall says. “However, in the next stage we will integrate the procurement and sales divisions into the project. All three parts are important to ‘IN-SPUR’.”

Audi special report: Vorsprung durch Logistik

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

Currently reading

Currently readingAudi special report: A fast, flexible network

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9