The fallout from the diesel emissions test scandals at Volkswagen and Mitsubishi may soon find something of a resolution – at least officially, when a fix is agreed with the US government, for example. Winning the trust of customers will be another issue. And the furore could have an even longer lasting impact on how emissions regulations are devised and enforced.

There are already signs of this happening: in mid-June, for example, EU regulators tabled proposals for stricter checks on fuel consumption and CO² emissions to plug perceived loopholes in the vehicle test process.

Much of the media attention over the scandals has focused on the potential for legal action, as well as on emissions testing and its relation to the real world, but there may also be broader implications for the logistics sector.

Volkswagen Group company Porsche, for instance, recently encountered problems in getting its new Macan models certified for sale in some US states because of a stricter insistence on compliance with the regulations laid down by the California Air Resources Board (CARB), leading to a brief period during which the cars were grounded at ports in the US. Although the cars were cleared fairly quickly without a huge bottleneck, the stricter certification was a direct fallout from the scandal at VW that raises questions about how far such restrictions will go in the wake of growing mistrust over official OEM claims, whether that might disrupt trade flows, and how cars are cleared.

‘Moving targets’Some, like Julia Poliscanova, manager of clean vehicles and air quality at the sustainable transport campaign group Transport & Environment, suggest that the biggest outcome of the debacle so far has been the damage done to EU regulation.

“Until now, EU car regulations, such as standards for CO² and air pollution, have been copied in many places around the world, making it easier for European industry to enter other markets. But this will change. Following the VW scandal, Beijing has opted for the US CARB system for its new air pollution standard, JING 6. In the past, the Chinese tended to copy EU regulations,” she told Automotive Logistics.

Christoph Stürmer, global lead analyst at PwC’s influential Autofacts division, said that since the testing scandal, the European emissions regulations had in effect become “moving targets”, resulting in ongoing increases in controls. “Especially with the upcoming RDE [Real Driving Emissions] testing, in-operation fleets are increasingly coming under scrutiny and will be subject to more intense surveillance and testing,” he said.

Rest of world to follow?Poliscanova said it was important to distinguish between climate change policy, including measures stemming from the Paris agreement, and air quality policy, including cutting NOx emissions, which has come to the fore since the VW scandal – not least since the two types of emissions have been regulated separately.

“In Europe, we already have good NOx and CO² standards – the problem is that they exist only on paper, with carmakers manipulating and cheating the tests while [vehicles are] emitting much more on the road,” she said.

Poliscanova predicted there would be “new and more representative tests” in Europe and a tightening of the testing system – a trend opposed by carmakers and vehicle-producing countries, such as Germany and Italy. Ultimately, she said, without such testing reform, new standards on either NOx or CO² “won’t bring many benefits”.

Whatever the benefits, a number of new EU and global emissions regulations are expected to emerge over the next few years – including the further development and improvement of the new RDE test and Type Approval reform, as well as post-2020 CO² standards and Euro 7 pollution standards for cars and trucks.

"In Europe, we already have good NOx and CO2 standards – the problem is that they exist only on paper, with carmakers manipulating and cheating the tests while [vehicles are] emitting much more on the road." - Julia Poliscanova, Transport & Environment

Stürmer agreed that regulations were “on the move to get stricter” but stressed this was nothing new. He said what the emission test scandals and the Paris agreements were most likely to do was “weaken the counter-arguments of the defenders of the automotive and logistics sectors, rather than fuel the ardour of politicians”.

“The truck sector has been well protected by its lobby groups but regulations requiring similar CO² emission reductions as the car sector will come,” he said. “I also expect logistics companies to become subject to the CO² emissions trading scheme.”

Dealing with truck emissions It is uncertain if the heavy truck sector, which is responsible for running the commercial vehicles that carry out most logistics movements, will face more stringent emissions regulations just yet. While European, US and Chinese authorities have all set emissions targets, much of the focus to date has been on passenger cars, though truck operators are still concerned about the potential long-term costs.

One strategy the sector has adopted is to call on the regulatory authorities to introduce a more transparent CO² testing regime. Last year, a number of haulier associations – including the IRU, CLECAT, the European Transport Board, the Nordic Logistics Association, Leaseurope, the European Express Association, and Green Freight Europe – sent a joint letter to the European Commission calling on it to propose a truck and bus CO² test (known as VECTO) that is “transparent, cost-effective and easy to use for third parties, with simulated results that can be verified through a form of testing for real-world compliance”.

Several companies have also sought to improve the emissions performance of their trucks via improved technology. US operator Cummins Westport, for example, launched a natural gas engine last year. According to the company, the model is the first mid-range engine in North America to receive emission certifications from both the EPA and CARB. The exhaust emissions from the new engine will be 90% lower than the current EPA NOx limit.

But automotive logistics may also face administrative hurdles. One major issue is the fear that the problems Porsche had with securing certification for the sale of its Macan model in some US states could be repeated more widely, potentially extending the time it takes for European and diesel cars to get clearance certification.

Poliscanova said there would “definitely be more suspicion and rigour” in certifying new diesel vehicles in the US in future. Not everyone agrees though. Stürmer suggested that once technical approvals had been issued, the clearance process would not be any more difficult than before. “It may require even more detailed documentation, possibly even with individual test certificates of individual cars, but that is more a problem for the OEM and an opportunity for the LSP,” he suggested.

In terms of cost, meanwhile, Stürmer said the ultimate impact on new vehicle prices would not be too great and claimed a number of factors, including production competition, would help push new technologies into the market “at almost zero increment”.

If predictions of tighter emissions controls in cities come to pass, smaller or cleaner vehicles may have to be used for delivery within their boundaries

If predictions of tighter emissions controls in cities come to pass, smaller or cleaner vehicles may have to be used for delivery within their boundariesThe long-term impact on operating costs, meanwhile, is another debatable point. Stürmer thinks the effects of more stringent CO² surveillance could be favourable to fleet operators as more emphasis will be given to “real fuel economy” instead of just one-off certification results. That said, he conceded tighter controls might force fleet operators to use more fuel additives, or oblige more of them to install replaceable soot filters that would increase operating costs.

Tighter controls could also affect the number and type of vehicles allowed to operate in given areas, including truck restrictions. “Cities will become increasingly picky about the vehicles they allow to operate in inner city areas, so heavy loads may have to be increasingly re-packed at the city gates [into smaller or otherwise cleaner vehicles] which may give rise to innovative ‘milkrun’ distribution services,” he said. “In addition to that, limits on which emission class of trucks may operate in which country may be introduced.”

Maximising efficiencyGiven the political and regulatory pressure to reduce emissions, the best strategy for manufacturers initially is to stop manipulating tests and focus on meeting the standards in normal driving conditions, said Poliscanova.

“All the technology to meet CO² and NOx limits exists and has been applied for years. What’s lacking is industry’s will to use that technology appropriately and calibrate engines in line with best available technology,” she said.

Looking further ahead, Stürmer suggested the most important change would be to minimise the amount of transport actually required by maximising the efficiency and speed of the entire logistics network, not just that of a single operator or handler.

“Shifting from single operator models to multi-operator platforms will require a lot of new thinking and technical controls, but with enough intelligence in the transported goods – whether it be the car, the component, or the packaging – new business models could arise to minimise global and local emission footprints,” he said.

"In short-haul transport, I think radical concepts such as electric trucks with swappable batteries, or robotised distribution systems – possibly even leveraging existing public transport infrastructure – will become a real alternative" - Christoph Stürmer, PwC

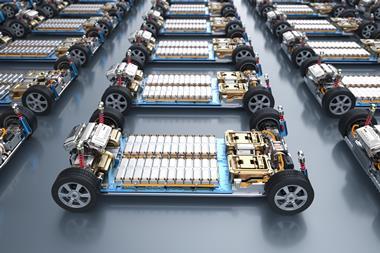

Future innovation should also be focused on allowing more seamless transitions between different modes of transport, he added. “In short-haul transport, I think radical concepts such as electric trucks with swappable batteries, or robotised distribution systems – possibly even leveraging existing public transport infrastructure – will become a real alternative,” he stated.

Poliscanova said that as the technology to meet the current and emerging emissions standards already existed, she was hopeful the industry would witness greater uptake of suitable alternatives in coming years, in particular urea-based SCR (selective catalytic reduction) engines.

“The problem with trucks, and often cars, is not so much that there is a lack of innovation or technology update at the design stage, but rather that a lot of this technology is either switched off or reduced in effectiveness during operation,” she said.

“For example, there are reports that drivers disable SCR on many commercial trucks for a variety of reasons, including not having to bother to replenish urea and to improve their driving characteristics. So what’s needed is more rigorous surveillance – through periodic technical inspections – of trucks that are already in use, to make sure they continue to meet the standards and use the technology fitted on them throughout their lifetime.”