Industries rise and fall, but logistics tends to remain.

Back towards the port, the road approaches a railway overpass painted in a familiar, although fading blue. On it is the logo of General Motors dotted with graffiti, and a yellow emblem marking the United Auto Workers union branch, local 239, that once represented the workers of a GM van plant that shut its doors after 70 years in 2005 (the union still represents retirees, as well as several component plants nearby).

Near the underpass, on the site where the plant once covered a long stretch of road, a low, gleaming white building, nearly as long as it is wide, is rising. The shape of a massive warehouse is already visible, its many loading bays already cut out; most are empty of trailers, but their iron curtains stare out, expectant and ready.

By next spring, Amazon will operate a ‘fulfilment centre’ here, which will receive thousands of trucks from manufacturers – including cargo off containerships – to be repacked and dispatched to customers in Baltimore and the northeast. There are also rumours that the online retailer will take over adjacent land to build another warehouse for its online grocery business. [sam_ad id=6 codes='true']

In the story of the West’s economic decline and change, large manufacturing plants and their supply chains are razed to make way for retailers, e-commerce and their supporting box centres and warehouses. It’s a cycle that has played out across this community as it has elsewhere. Only a few miles away, across a stretch of the harbour, sits the remains of what was once the world’s largest steel plant, at Sparrows Point, a site whose future will be decided between the state-owned port and developers. As the story goes, jobs barely above the minimum wage, and often on temporary contracts, replace those that paid decent wages and benefits. Amazon, known for a ruthless focus on productivity and high numbers of temporary staff, can certainly play the part of the villain.

The reality, as ever, is more complex. On one hand, Amazon executives (or at least its public relations team) are aware of Dundalk’s collective memory: the company has stressed that it will hire more than a 1,000 full-time positions with better pay than retail workers, including a variety of pension benefits and education tuition support.

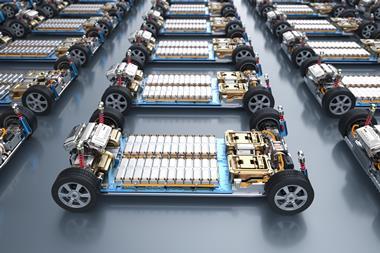

Neither does the warehouse tell the full story of automotive’s rise or fall in Baltimore or in the wider US. The port’s vehicle terminals now handle more cars and rolling equipment each year than any port in the country. Vehicle processing centres thrive here as extensions of plants, carrying out inspections, repair work, accessory and option installations. WWL’s processing centre for Subaru, for example, is running on two shifts. Meanwhile, carmakers including Toyota, Honda and Detroit OEMs are increasing exports from the port.

Some things come back

None of this is to pretend that such jobs are equal in number (or worth) to the assembly plants now gone. In the 1970s, the GM plant in Dundalk employed around 7,000 people, albeit just 1,100 when it closed. Still, many do not see the Amazon warehouse as another drop in the low-wage ocean. The port’s processors and carmakers are worried that it will deplete an already limited labour pool, as companies struggle to find the resources they need today. Such a shortage does not imply a booming, high wage community – Amazon learned much about its warehouse productivity from the automotive industry, after all – but it shows how sophisticated logistics services remain in high demand.

Despite rising vehicle assembly in the US, direct employment at plants is unlikely to approach former highs. Still, the expansion is evident in logistics and plenty of examples invert the Amazon takeover in Baltimore. Right in Dundalk, BMW is expanding its processing operations after changing facilities and providers. The port itself is also adding land used for automotive, some of it reclaimed from dredging the otherwise drowned soil of the Chesapeake Bay.

To see more, you have to get off the Broening Highway. Cross over the harbour on the Francis Scott Key Bridge and travel 2,500 miles to southern California, where close to the port of Long Beach, Mercedes-Benz is taking part in its own form of industrial renewal. On the site of a former Boeing factory, the carmaker is opening a west coast campus with corporate offices and a sprawling centre for parts and vehicle preparation. Logistics, it would seem, adapts to that which rises, flies, comes back to earth and changes all over again.