Kuehne + Nagel is supporting its automotive customers’ transition to an electrified future with the provision of battery chain services. At an event the company held in December, mobility and materials experts discussed the challenges facing the industry. Marcus Williams reports

The automotive industry’s transition from a producer of vehicles powered by combustible hydrocarbons to a cleaner one driven by electric batteries is perhaps the biggest upheaval in its history.

In certain regions of the world – China and Europe to name two – government initiatives are dictating that vehicles driven purely by internal combustion engines (ICE) will be gone by the end of the next decade. Many carmakers are already offering electric versions of their products, with Chinese and European manufacturers again front and centre.

However, the penetration rate is going to be dictated by the supply of lithium-ion battery and the global prevalence of the plants that make them.

It takes between five and seven years to fund, build and ramp a lithium mine if all goes well, according to Simon Moores, managing director of Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, who was speaking at Kuehne + Nagel’s Automotive and New Mobility Digital Conference, held on December 10. Added to that, it can take 18-24 months to build a battery making plant, while the average development cycle to bring an electric vehicle (EV) to market can also be around seven years. Mines and battery plants are being built, and carmakers old and new are bringing EVs to market but there are regional disparities in the development and supply of materials.

Those regional disparities in supply are frustrating the efficient development of a new energy vehicle supply chain and making it unlikely the industry will be ready in a decade. It is a problem further hampered by the impact of economic stagnation and Covid disruption on the investment plans of major OEMs and EV start-ups alike.

Complexity breeds opportunity

That is where logistics providers, such as Kuehne + Nagel, are seeing a demand for new services and are responding. According to Detlef Trefzger, CEO of Kuehne + Nagel, managing uncertainty and responding with agility to changes in the automotive industry to provide better visibility are essential parts of the company’s business model.

“Applying technology and connectivity, interfacing with our customers and understanding their needs…is what drives the business model globally, and this is key to the journey we are taking to bridge troubled waters,” said Trefzger (Kuehne + Nagel named its conference after the Simon and Garfunkel song).

While the number of parts in an EV are significantly lower than a traditional one driven by a combustion engine there is still a complexity to the parts required in a car that is electric and more digitalised. That makes new demands on transport and logistics.

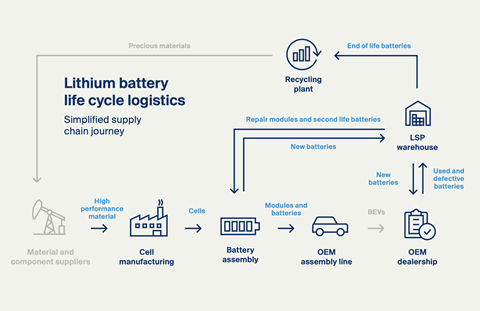

The most essential part of an EV is the lithium-ion battery, which comes with a range of new demands for storage, inbound transport and recycling. That is why Kuehne + Nagel has developed a solution called KN BatteryChain to provide customised transport and storage services for automotive customers.

“While there will be fewer parts the complexity and integration into the manufacturing process increases and that offers opportunities for a company like Kuehne + Nagel,” said Trefzger. “There will be new consumer demand leading to new service requirements around mobility and this offers new opportunities for us as a transport and logistics company.”

Supply shortfall

There is plenty of opportunity at the moment as there is also currently nowhere near the capacity for lithium battery supply in Europe required to meet the level of EV production if 2030 targets for alternative propulsion are to be met.

According to intelligence from Ultima Media’s Automotive business intelligence unit, the market share of new vehicles with hybrid or electric powertrains will rise dramatically from around 8% today, to 55% by 2030. Pure petrol and especially diesel-based powertrains will see double-digit declines over the decade.

However, the rate of regional adoption will vary according to regulatory differences, purchase subsidies, charging infrastructure and consumer preferences. In both Europe and China, sales of fully electric powertrains are forecast to increase nearly sevenfold by 2030.

The difference between those two regions, however, is that the majority of battery gigafactories are in China. According to Moores, of the 174 gigafactories that are either already active (114) or in the pipeline for production, 87 of them are in China. Four of the active plants are in Europe and four are active in the US.

Europe has been working harder to redress the balance, with plants either open or planned to open in the next year in Germany, Hungary, Poland and Sweden. CATL’s plant in Germany is due to open in Erfurt in 2022, supplying BMW, Daimler, Volvo and VW. BMW and VW are also to benefit from supply in Sweden when Northvolt Ett opens its plant there next year, with additional plans to build a joint venture plant in Salzgitter in 2021. Samsung SDI already has a plant in Göd, Hungary and is opening another 2021, while SK Innovation opened one in Komarom this year.

Raw materials

The most critical element in the success of a battery gigafactory however, is the volume supply of raw material from the ground.

“That is challenge number one because you now have an unprecedented scale hitting the industry and the demand is getting bigger,” said Moores.

Localising supply of components and materials is one of the main challenges in establishing a battery gigafactory in Europe, according to Philippe Chain, co-founder and chief customer officer, Verkor. His company is looking to build just such a factory in France, with the support of EIT InnoEnergy Schneider Electric and Groupe Idec and an initial investment of €1.6 billion ($1.91 billion).

According to Chain, the list of materials and components to localise is long and includes battery and battery cell components, including separators, electrolytes, chemical compounds and mechanical parts, but also the active and raw materials.

“That is going to be the challenge: to actually to build a European battery manufacturing ecosystem,” he said.

That ecosystem needs to be more sustainable and ethical that it is currently, said Moores. Properly converting the raw materials into the specialty chemicals that need to go into a battery is crucial because there are specifications that need to be met for the battery maker.

“Whether it is lithium, cobalt, graphite, nickel or manganese – the chemicals that go into the cathodes and anodes have to be specially made for the customer and high spec,” said Moores. “The automaker has to balance all five of these and ensure they have a steady, consistent supply at a reasonable price so they can keep pushing the cost of the battery down.

Coverting those materials into chemicals causes waste than needs to be properly managed. Waste-water disposal is a big issue in China as is the disposal of the acids used in purification of materials used in lithium batteries.

At the same time, human rights abuses in the Democratic Republic of Congo, one of the main sources for cobalt extraction (though not the only one) are well documented.

There is also the question of whether the energy used to mine and supply the materials is itself carbon intensive. Building batteries takes a significant amount of energy, observed Chain: “If we have access to low-carbon energy, which is the case in some European countries, that is going to be a huge advantage in lowering the carbon footprint of battery manufacturing.”

There are five stages in getting raw materials out of the ground and into a lithium-ion battery and each of them have ethical questions attached. According to Moores, the key to building a responsible and transparent supply chain in the 21st century is getting as much control over the supply chain as possible and localising supply.

Disrupting the energy sector

The process is as complex as the more general issue facing the automotive industry at the moment, namely the undoing the production supply based on combustion and what the new energy vehicle revolution means for the petrochemicals industry supporting it.

According to Graeme Edge, entrepreneur and co-founder of Energy Disruptors, and event that promotes collaboration to bridge new and existing energy providers, European companies such as Shell, BP, Equinor and others, have announced ambitious new energy business strategies in the last couple of years.

“A lot of them are not yet being rewarded for that in terms of how that is being received by shareholders and stakeholders but they have certainly announced a clear ambition to be part of energy transition, and lot of that has been driven by the changes happening in the new mobility space,” he said.

However, those companies are still trying to identify where participate in the value chain while playing to their existing core strength. Running an electricity business heavily reliant on renewables is very different to mining oil and gas, observed Edge. As a result, many are talking about spinning their new energy businesses into separate entities.

Edge was more critical of US companies that were “laggards who wanted to stick to their core business and not participate in new energy” and said Canadian energy companies were caught somewhere in the middle between the US and Europe.

To be fair, there are regional differences in the US based on how carmakers see a way of making money from the transition to both EVs and the new mobility patterns of use in the customer base.

Boris von Bormann, founder and managing partner of Renu Ventures (and a former CEO of Mercedes-Benz Energy), said one only had to compare the proliferation of Uber EVs in California and the personal ownership of pick-up trucks in Texas, where customers are simply not served by new mobility and don’t have an adequate charging structure to cover such a large state.

“We have seen Chrysler, Ford and GM struggling with new technology and EVs, and new mobility. You see significant M&A activity for these companies to catch up, but it is very difficult for the incumbents no matter where you are to stay on par with the transition,” said von Bormann.

Edge added that companies that were trying to make the shift would be rewarded but the path was fraught with challenge and danger. A lot of the companies and the regions in which they operate rely heavily on hydrocarbon revenues.

“It will likely take decades to decarbonise global energy, and oil and gas still has a role to play, [but] the industry should be looking to the future for opportunities around energy transition,” said Edge. “These are massive, complicated challenges and what we need is collaboration rather than antagonistic viewpoints between different parts of the energy sector.”

Urgent need for change

What is also needed is a sense of urgency, according to Angelika Berger-Sodion, executive vice-president, People & Brand, at MOV Automotive, which advises on lowering carbon output in transport. That urgency is needed because most western companies underestimate the need for change to a more sustainable industry, compared with those in China, she said.

“The key lesson learned for me is that China has this unique combination of a very ambitious and very articulated ambition on the one hand, but also on the other the ability to make changes on the go – what I would call dynamic execution,” she said. “That is what has made them strong over recent years – they had a clear strategy that was clearly communicated but they maintained agility and flexibility on the go.”

The development of the battery supply chain, including the proliferation of gigafactories, has also been helped by government incentives for EV purchases over a number of years and the fact that vehicle makers there are not hampered by legacy issues stretching back to the beginning of the car industry – domestic passenger car production in China only really got going to scale in the 1990s (though imports started to grow from the mid-80s). Since then however, production in China, initially through joint ventures, has proliferated.

According to Bill Russo, founder and CEO, Automobility and chairman of the Automotive Committee at AmCham Shanghai, that longer legacy of western carmakers is now hampering their ability to adapt to change.

“When you deal with an industry with a 100-plus year history of incumbent technology you have a schizophrenic capital plan,” said Russo. “First you have to wake up to the reality of discontinuous change. We have to be clear. Disruption is when a fundamental business model has shifted to something other than what you have historically been accustomed.”

Carmakers based on volume-based planning are trapped in a capital-intensive industry and one that requires a massive amount of capital to just keep the engine turning, said Russo.

International cooperation

China has freedom and support to develop an EV industry, as seen in the number of EV start-ups in the country.

“They can start on a clean sheet of paper and don’t have to restructure their businesses,” said Berger-Sodian. “[Start-ups] can focus straight on user experience.

That said they are not guaranteed success and the further challenge is in how to go international because while they are strong in China they have not started to develop international expansion plans.

That is beginning to be an incentive for more strategic discussions between companies, though this is anything but consistent at the moment.

“There are examples of cross-cultural ideas and investments, and new strategic partnerships emerging. There is quite a lot going on,” said Berger-Sodian. “What am I also seeing and what encourages respect is for the legacy companies who are transforming themselves from inside out and totally changing their business models.”

Those companies have to respond to a confluence of forces transforming the industry, including the energy, the propulsion technology, the materials (and access to them) that power the vehicle. There is also a geopolitical angle to where the supply chains are located, and where companies can buy their batteries.

“All these are decisions you have to make as a business,” said Russo. “How do you plant your flag in the right location so you can build where demand is and you can get materials in from where you need to get them.”

One of the others is in having the right logistics provider to support the delivery of those materials and it seems the right logistics provider is also one that can transform themselves to meet the demands of a new energy future. That is a capability that Kuehne + Nagel’s CEO thinks the company has.

“[Change in the automotive industry] has accelerated over the last year and it’s also true that we face transformation in transport and logistics,” said Trefzger. “At K+N we want to be a leading partner for the transformation of our customers in the different industries. We have invested in digitalisation, technology [and] connectivity, as well as innovation to anticipate and drive changes that are happening in the automotive industry

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet