Despite negligible EV sales at home, South Africa is looking to become an exporter of their components and is putting an incentives scheme into place. But can it succeed?

South Africa has developed the only automotive industry among its regional peers, but now it wants to go one step further: adding electric vehicles (EV) to its export portfolio. On the surface, this may seem like something of a stretch for a market in which the electrification concept has yet to take hold with either consumers or manufacturers.

Looking at the South African market as a whole, around 365,000 passenger cars and 290,000 trucks and buses were sold in 2018, while 334,000 vehicles were exported. Altogether, the local automotive industry, including vehicle components, brought 164.9 billion rand ($8.9 billion) into the country during this period, which represented almost 14% of total South African exports.

The statistics for EVs are startling: last year, only 66 EVs were purchased in South Africa and no EV sales at all were recorded in the rest of the continent, according to Andrew Kirby, president and CEO of Toyota South Africa. Toyota is the largest vehicle-maker in South Africa, where it manufactures five models: the Hilux, Fortuner, Corolla, Corolla Quest and Quantum.

“I think the South African public is quite progressive, and it would not take too long to move towards alternative drivetrains if they were available at affordable prices, and with the necessary infrastructure” – Andrew Kirby, Toyota South Africa

Few EVs are included in the Toyota lineup, but the occasional imported Prius and Yaris hybrid does appear in the Japanese OEM’s South African showrooms. In Kirby’s opinion, what is lacking is an incentive structure similar to those made available to many other markets around the world.

“I think the South African public is quite progressive, and it would not take too long to move towards alternative drivetrains if they were available at affordable prices, and with the necessary infrastructure,” he said at Toyota’s annual state-of-the-industry address in Johannesburg in February.

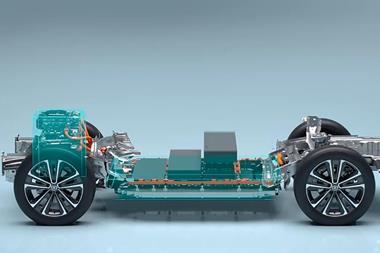

Now, for the first time, the government and local industry are indeed considering incentives, aimed at helping manufacturers to produce the critical components used in EVs: batteries, electric motors and related components.

A helping hand

That South Africa’s current automotive industry exists is largely due to an incentive scheme, the Automotive Production and Development Programme (APDP), which allows carmakers to import models in their overall lineup with reduced duties, provided that an equivalent value of vehicles and components is exported.

As a result, manufacturers have set up streamlined plants in the country to focus on specific models destined for their global customers. At the same time, they are able to import a broad range of models to suit local customer needs.

For instance, BMW South Africa uses its plant in Roslyn, Pretoria to manufacture its X3 SUV, which it exports worldwide – including to Germany. At the same time, the OEM sells nearly 50 different models in South Africa which it imports from its international plants.

“The automotive sector contributes 7.7% of the GDP of this country,” said Tim Abbott, CEO of BMW South Africa at a press briefing in February. He added that half a million jobs in the country rely on the automotive industry.

The APDP has resulted in some of the largest vehicle-makers from the US, Europe and Japan maintaining a presence in the country. In addition to BMW and Toyota, Volkswagen (VW), Nissan, Ford and Mercedes also have production operations in the country. Recently, a Chinese OEM also entered the fray; at the beginning of August last year, China’s fifth-largest vehicle manufacturer, BAIC, opened a plant in Port Elizabeth, on the east coast.

”We want to encourage automakers to trade in intermediate products such as powertrains. This is the direction we are headed” – Rob Davies, South African minister for trade and industry

It is generally agreed that without the APDP and government backing, South Africa’s automotive industry would not survive in the fiercely competitive global environment. As pointed out by BMW’s Abbott, the fate of Australia’s car industry is an illustration of what can happen when government pulls the plug.

“The government in Australia chose not to support the automotive industry six years ago, and it took just five years for the industry to leave the country completely,” he noted.

The South African government is well aware of this, and so the APDP which expires in 2020 will be replaced by a revised version. Apart from modifications that aim to close gaps in the current programme, the new version will also include a subsection on tariff relief for companies that export electric powertrains.

Focusing on components

Realistically, South Africa has little hope of competing directly in the global EV market through exporting fully built cars, which is why the government plans to focus on specific components instead.

Speaking on the sidelines of a mining investment conference in February, Rob Davies, minister for trade and industry, said the country could bypass exporting completed vehicles and instead earn credits for critical systems. “We want to encourage automakers to trade in intermediate products such as powertrains. This is the direction we are headed.”

Currently, a tariff of 25% is in place for electric cars, while electric buses and trucks carry a duty of 20%. These are likely to stay, but export credits similar to those for completed vehicles will now be offered to makers of critical parts for EVs.

Davies noted that South Africa’s automotive manufacturers are logistically well positioned to export high-value components; OEMs and tier suppliers are clustered around the coastal cities of Port Elizabeth and East London, which gives them ready access to global trade routes.

Those which are located inland – especially around Pretoria, such as Ford and BMW – benefit from a good road network as well as a freight rail service linking them to the east coast.

Meanwhile, South Africa’s busiest port, Durban, is also supported by a good rail link and road network that leads into Gauteng province 600km inland, which is also the country’s industrial heartland.

EVs and FCEVs in tandem

Electric drivetrains are not only used in EV manufacture; they form the basis of another alternative to internal combustion engines which is also being backed by the South African government: fuel-cell electric vehicles (FCEV).

FCEVs, which rely on a catalytic reaction to generate electricity from hydrogen, are vying with EVs in the worldwide race to supplant petrol and diesel technology with new forms of mobility. Globally, there is some debate over which represents the best option. CEO of Tesla, Elon Musk – who, incidentally, hails from South Africa – has been widely quoted as branding the rival technology as ‘fool cells’ – one of his less colourful descriptions of them.

Musk has occasionally hinted at making the cheapest car in the Tesla range, the Model 3, available in his native country. Last December he responded to a query on when Teslas would be seen in South Africa, by saying: ‘Probably the end of next year.’

Although they have their own drawbacks and have lagged behind batteries as a cheap, easy way to power vehicles, they do offer the advantage of a long range and a short refuelling time. One important point for South Africa is that they also use platinum in their systems, and since the country produces 70% of platinum supplies worldwide, the government and local industry have been eager to encourage their development.

The government recognises that batteries as well as fuel cells can work in tandem, however. Davies said: “Fuel cells can be fitted to a battery-electric drivetrain and act as a range extender.”

He pointed out that EVs and FCEVs share many components, as all are ultimately electric vehicles; only the energy source itself is different. Whichever technology comes out on top, the need for certain critical components will still need to be met.

“We’re no longer betting on one or the other technology – we’re neutral on both,” he stated.

Charging up

Looking at a number of recent developments, efforts to put South Africans behind the wheel of EVs are gaining momentum. In February, Anglo-Dutch energy company Shell said that it would commence building a nationwide network of charging stations in the country.

“This is part of our roadmap to 2025,” Dineo Pooe, spokesperson for Shell South Africa, told Automotive Logistics. “We will start small in 2019 and ramp up as demand increases. Shell, together with its strategic partners, will make this investment.”

EVs could also help South Africa with another logistical squeeze on its economy: the burden of fuel imports. South Africa is dependent on crude oil imports, which are processed in old refineries on the east coast.

Last year the country spent 54 billion rand on foreign oil, about 12% of its total import bill. Due to the age of its refineries, the fuel produced lags behind international emissions and efficiency standards. Last year, energy minister Jeff Radebe told parliament that this meant that petrol or diesel vehicles destined for South African roads could not use the latest-generation engines.

“The current refineries are not equipped to produce the latest fuels required by modern vehicle engines to reduce vehicle emissions and improve efficiency,” he said.

Besides Shell, several other national fuel service chains are also considering introducing fast chargers to their forecourts as South African support for EVs grows. More vehicle retailers are coming on board as well.

Jaguar Land Rover, the UK carmaker, introduced its all-electric I-Pace to the South African market in March. It too will set up a chain of chargers along main routes, which it calls ‘Powerway’. These will be 60kWh fast chargers which can deliver 100km of range in around 20 minutes, or just over an hour to go from zero to 80%.

“It’s an inevitable technology, and Jaguar Land Rover is adopting it early,” said Brian Hastie, the company’s network director and electrification project lead, at a press briefing in Cape Town in March. “As we become more electric-vehicle savvy, this will become an everyday technology that the consumer will adopt very willingly.”

VW, too, has started seeing the potential of EVs in South Africa. Earlier this year it brought motoring journalists to Cape Town to see an as-yet-unnamed demonstration model put through its paces.

Power problems

However, if South Africa is going to gain a foothold in EV manufacture and sales, it will have to do something about the self-inflicted electricity crisis the country is currently experiencing. The state-run power utility has recently imposed electricity rationing, cutting off power to factories and homes for hours every day.

Eskom is burdened with debt and a fleet of ageing coal stations prone to breakdowns, while poor engineering and workmanship have also reduced the availability of the new stations meant to replace those headed to retirement. At this point it is unclear whether the government has figured a way out of the problem.

“The truth is, Eskom coal generator units operate intermittently, and when on, they often do not deliver full output,” Chris Yelland, an energy analyst based in Johannesburg, told Automotive Logistics. “The Eskom coal fleet requires back-up from flexible generators, like pumped energy storage schemes, hydro power and open-cycle gas turbines.”

A wave of power outages of eight hours a day in late March proved extremely disruptive, and it now seems likely that the government may at last begin licensing independent power providers, especially those which supply renewable solutions, such as solar and wind generation.

The country is blessed with strong sunshine and wind and an existing fleet of renewable energy plants has been productive. If South Africa can get its energy policy right, and sort out its power crisis, the country could have a role to play in future green automotive technology.

Green buses a non-starter

In the last few years, the city of Cape Town has taken tentative steps towards electric public transport, announcing in 2016 that it would pursue a pilot project to test battery-powered buses. This was to be done in conjunction with BYD, the Chinese manufacturer which claims number-one spot in global EV production. Under the plan, BYD would provide a test fleet and build a local assembly plant.

In August last year, however, local newspaper The Sunday Times reported that the fleet of 11 pilot buses was having difficulty navigating the steeper routes which snake around Cape Town’s mountainous geography.

At the same time, Cape Town had also initiated a forensic audit into BYD, looking into allegations that senior city officials had steered the contract towards the Chinese company after unauthorised meetings. Reports suggested that Cape Town wanted to recoup the 130m rand it had paid BYD, and bring the project to a halt.

Contacted by Automotive Logistics for comment on the project, Cape Town spokesperson Luthando Tyhalibongo declined to provide details on the status of its electric bus project. “The City of Cape Town is unfortunately unable to comment at this stage as we have not implemented electric buses as part of our MyCiTi bus service fleet as yet,” he said.

Patricia de Lille has since resigned as mayor, in part because of the troubled bus project.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet