One of the most popular songs about the US state of Alabama, ‘Sweet Home Alabama’, opens with the line “Big wheels keep on turning” – and indeed the number doing so is set to grow after the January announcement that a $1.6 billion Toyota-Mazda joint-venture manufacturing plant is scheduled to open in Huntsville in 2021.

One of the most popular songs about the US state of Alabama, ‘Sweet Home Alabama’, opens with the line “Big wheels keep on turning” – and indeed the number doing so is set to grow after the January announcement that a $1.6 billion Toyota-Mazda joint-venture manufacturing plant is scheduled to open in Huntsville in 2021.

Since 1997, when the first M-Class car rolled off the Mercedes-Benz production line in Tuscaloosa, the wheel – along with all the other components found in a modern vehicle – has helped Alabama to reinvent itself as an epicentre of the automotive industrial revolution that has taken place across the south-eastern US.

While the state’s borders may not have expanded in nearly 200 years, the map of Alabama, which now possesses enviable global market links, has been strategically redrawn over the past 20 years with the arrival of four automotive manufacturing plants and a tier supplier network in excess of 170 companies. According to state officials, Alabama has manufactured more than 10m cars and light trucks since 1997 – making it the fifth-largest car and truck producer inthe country.

State and local planners have been both persistent and mindful of the big picture in encouraging and locating vehicle manufacturing plants and tier supplier locations there. In addition to the Mercedes-Benz US International (MBUSI) facility in Tuscaloosa, Honda operates a plant in Lincoln, Hyundai works out of Montgomery and Toyota manufactures engines in Huntsville.

“I think there was an awakening as a result of that first automotive assembly project coming to the state,” observes Greg Canfield, secretary of commerce for the state of Alabama since 2011. “It was an awareness coming to Alabama that we could be a state that had – and offered – more. We were a state in the south-east that no longer had to base its economy on basic manufacturing, agriculture and timber. We could go beyond that to advanced manufacturing, technology and things like that. It’s been a 20-year awakening for the state.”

Jason Hoff, who oversees the Tuscaloosa operation as president and CEO of MBUSI, has a special perspective on the growth and evolution of the Alabama automotive industry. Although Hoff took up his current duties in 2013, he was previously part of the initial team responsible for launching the Tuscaloosa plant in the 1990s.

“I would say that 20-plus years ago, we knew we had picked the right area to come to. We were really confident about the conditions here – from the workforce, to the infrastructure, to the general support of the region,” he says. “Could I have envisioned what the state has become today? That probably would have been a little far-fetched, but it’s not a surprise to me now that other companies [OEMs] have followed suit. It’s a good place to do business down here. With this most recent announcement, I hope we can capitalise on the fact that this is an automotive mecca. Hopefully, that will attract more people to consider relocating here.”

Supply chain strengthThe Toyota-Mazda location decision ended up being between Huntsville and a site outside Greensboro, North Carolina. In the end, it was swung by the strength of the working model Alabama had built in collaboration with the automotive sector, which provided advantages and synergies other bids could not match. According to a North Carolina media outlet, records released by that state’s Commerce Department revealed some serious competition at the time in the form of a bid by the state and local entities worth as much as $1.8 billion in incentives. But Alabama still won out.

A spokesperson for Toyota confirms that the presence of other OEMs, the state’s existing supplier network and the general infrastructure Alabama has developed over the last two decades or so all contributed to the final decision.

Toyota and Mazda officials say they are only in the early stages in many areas of bringing the Huntsville operation to life and are not prepared to share further details yet. The office of Huntsville Mayor Tommy Battle, however, has confirmed that a supplier park will be included as part of the overall project site. Once production at the plant begins, Toyota will manufacture the Corolla there, while Mazda will use the facility to launch a new crossover model in the North American market.

Despite the strength of the North Carolina bid, Canfield says he is not surprised that the logistical advantages of Alabama led to the decision to make Huntsville the home of the joint venture plant. Along with the supplier network and the state’s history of success with automotive plants, Alabama, he points out, has six interstate highways providing both north-south and east-west access; five class one rail lines; a deep-water port; and automotive industry operations within close proximity in the neighbouring states of Mississippi, Georgia and Tennessee.

“Incentives are important – but they are certainly not what drives the decision on a deal. They [Toyota-Mazda] knew that they could easily access an existing supply chain and look to grow their supply chain as needed,” says Canfield. “In my opinion, that made that cost-benefit equation relative to any difference in the incentives offered by North Carolina versus the incentives offered by Alabama immaterial.”

“Incentives are important – but they are certainly not what drives the decision on a deal. They [Toyota-Mazda] knew that they could easily access an existing supply chain and look to grow their supply chain as needed,” says Canfield. “In my opinion, that made that cost-benefit equation relative to any difference in the incentives offered by North Carolina versus the incentives offered by Alabama immaterial.”

The influence of the south-eastern automotive supply chain on trade within the Nafta region cannot be overstated. It has become a valued resource for a number of Mexican automotive concerns. And in addition to shipments coming across the border to southern-based OEMs, a growing number of south-eastern tier suppliers now ship components back to Mexico.

The influence of the south-eastern automotive supply chain on trade within the Nafta region cannot be overstated. It has become a valued resource for a number of Mexican automotive concerns. And in addition to shipments coming across the border to southern-based OEMs, a growing number of south-eastern tier suppliers now ship components back to Mexico.

According to Ryder’s Dave Walby, the network built across Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee is one that can benefit transport providers beyond the ability to book consistent freight.

“If I have someone building a part and he’s building a million of them now, with 500,000 going into Mexico and 500,000 going into the south-east, it can run on that corridor between Laredo and you hug the Gulf Coast up through Mississippi, Alabama and Arkansas,” says Walby. “We’ve now got a couple of great relay systems in place, and it helps with driver recruiting. Drivers can go back and forth, be home every night, and the product never stops. The wheels are moving 24/7.”

“Quite a few years ago, there were a few tier suppliers down there that would support the big three – GM, Chrysler and Ford. Now the south-east has become a manufacturing region and that expands the opportunities, and what needs to be done,” says Walby. “While suppliers have changed over the years, you still have suppliers from the Midwest supporting those plants down there. The plants still get 5-8% [of inventory] from their original countries. Mexico has also gotten big [as a supplier]. So, you have the north-south corridor from the Rust Belt, and now you have the south-east corridor – with some of it [the parts flow] coming from Mexico. It’s added challenges and complexity in so many ways.”

In Walby’s experience, the new landscape in automotive manufacturing includes plants that have been reduced in size from 2m sq.ft, including onsite warehousing, to facilities with 600,000-800,000 sq.ft. Additionally, more OEMs are producing multiple lines of vehicles – and frequently adjusting the vehicles produced during any given week based on metrics they collect from an abundance of available data.

“If you looked ten years ago at some of these plants, you couldn’t get near the line because the inventory was all over the place. Now you go there and you see literally what they need to build that day – even for two to four hours. That’s the change in some of the philosophies,” says Walby.

That’s made it ever more important to have a tighter network of suppliers and well-planned logistics support based on the wealth of information, he adds. “OEMs can now be very aggressive in the amount of safety stock that they have to keep. Instead of having eight to ten days, they can now go down to, say, three days. If you wanted to, you could even go down to one day. It’s changed how they have managed their inventory going into the plant.”

The bid process for a new OEM plant has also undergone some evolution over the past decade, according to Walby. In the past, an OEM might typically issue the initial bid a year to six months out from pre-production. As the processes have improved in mining all the data related to total landed cost for each vehicle, however, OEMs have begun to study their options for transport providers long before plant construction nears completion. By using all the available information, the design of both the supplier and transport networks allows OEMs to better control total landed cost.

“The further out you can start to design and begin working with your network and logistics, the more efficient it becomes for your supply chain,” notes Walby. “Any [plant] start-up is a bit difficult but, when you are starting out with a lot better information and visibility, you are able to take that risk out of the start-up. You know how your plan is going to run.”

The process Ryder employs when looking at serving a new OEM facility involves a series of tests against various scenarios. And with many customers now planning up to three to five years ahead, Ryder has applied a similar forecasting approach with its automotive customers at existing plants.

[mpu_ad]Among the questions addressed during this process, says Walby, are:

• Should the OEM source from Mexico?• Should it produce the components in the US? If so, which ones?• Should it use a global source?• How much inventory must be carried?• How are the shipments going to be handled?• What types of transport are needed? Will shuttles be necessary?• How are the shipments going to be presented?• What will need to be sequenced?• What is the total landed cost?

“You have to start looking at your supply chain from [the lineside] and then all the way back to the original tier supplier,” says Walby. “If you look at everything involved, that process allows you to take your plans forward to when the plant is going to reach maximum production.”

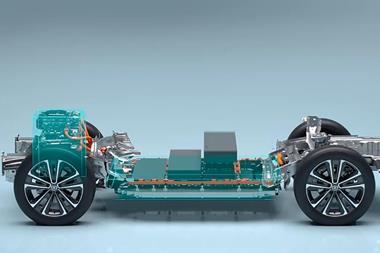

Continuous evolutionAs the experience of Mercedes-Benz with its Tuscaloosa plant shows, facilities are continually evolving – even after 20 years. One of the modifications that MBUSI made to its supply chain component flow was the development of an onsite logistics centre in 2014. Once MBUSI begins production of electric vehicles alongside traditional internal combustion models in Tuscaloosa, the logistics centre will unquestionably become even more valuable. Currently, it helps MBUSI in managing its two main classifications of inventory – components coming from Europe and those from the Nafta-based supply chain.

The logistics centre at MBUSI’s Tuscaloosa plant will play an integral role in its production of electric vehicles alongside combustion models

The logistics centre at MBUSI’s Tuscaloosa plant will play an integral role in its production of electric vehicles alongside combustion models“When we started 20 years ago – and I was here in the late 1990s – I can remember visiting a lot of our supplier operations and those operations were just for us,” notes MBUSI’s Hoff. “When you go into those operations today, you don’t see that any more. Rarely do you see a plant that is solely dedicated to just one OEM. With some of the new suppliers that we are taking on for our next generation of vehicles, they have a larger logistics service provider next to the plant or near the plant. They can also store a little more inventory or have a bit of a buffer, and they can still meet the logistics requirements that we have placed on them.”

Looking ahead, the obvious question is whether Alabama has the capacity for a sixth OEM plant.

“Our strategy has been to locate automotive OEMs regionally in different areas of the state such that there is very little to no overlap in terms of their labour share draw, and I think that we have done a good job of that,” says Secretary Canfield. “We have one area in the southern part of the state remaining. And we’ll see.”

The level of influence an existing tier supplier network can have on decisions by other OEMs to locate in any given area is amply demonstrated by Volkswagen’s Chattanooga plant, set up in 2011 around 110 miles north-east of Huntsville in Tennessee. VW launched the Chattanooga plant with the Passat and most recently added the Atlas mid-sized SUV to the production line.

The level of influence an existing tier supplier network can have on decisions by other OEMs to locate in any given area is amply demonstrated by Volkswagen’s Chattanooga plant, set up in 2011 around 110 miles north-east of Huntsville in Tennessee. VW launched the Chattanooga plant with the Passat and most recently added the Atlas mid-sized SUV to the production line.

“When you are talking in general about setting up a new plant, and in our [particular] experience, you use previously installed supply chains, which are usually from other OEMs where you have common suppliers. You also have strategic suppliers for big volume, which happened here, and those come in around the facility,” comments Paulo Monteiro, senior manager of supply chain logistics at the Chattanooga plant.

“Moving forward, if you have projects large enough to attract the big volume suppliers, then they will locate around the facility. Also, as new models are coming in, more volume will allow you to attract more suppliers.”

Despite over a decade elapsing since VW’s decision, Huntsville Mayor Tommy Battle says he can still vividly recall the moment he believes it lost out to Chattanooga as the location for the new VW plant. It happened during a helicopter ride with VW officials to get an aerial view of Huntsville’s proposed location.

“We were looking at land we thought would be great, and then they looked to their left. They asked: ‘What about that land? Is that land available?’. Unfortunately, it wasn’t [at the time]. Today, that’s our mega-site,” says Battle, of the spot that will now be home to the new Toyota-Mazda plant.

Although in a neighbouring state, VW’s Chattanooga site still demonstrates the drawing power of the automotive production infrastructure that has taken root in Alabama and right across the south-east. It placed VW in close proximity to Alabama’s well-developed automotive network as well as plants and suppliers in Tennessee, Georgia and the Carolinas.

“You had a big pocket of suppliers in the Michigan and Ohio area, but, as plants have opened up, you have a much larger supply base going through South Carolina, Tennessee, Alabama, North Carolina and Georgia,” remarks Eric Reilly, manager of pre-series logistics at the VW Chattanooga plant. “You want to start with a mature supply base when you launch. Then, as you build, you look at where you can optimise.”

Broadening the base, but locallyAlong with initial use of the traditional Midwest supplier network that was already familiar with the company’s intricate processes, VW accessed the supplier networks working with BMW in South Carolina and Mercedes-Benz in Alabama. As production moved forward, following the plant’s launch in 2011, the OEM continually broadened its supplier base to include providers within Alabama’s I-65 corridor. In addition to leveraging established networks, VW’s focus on maximising efficiencies served as a primary driving force in the development and continuing evolution of the supplier park supporting the Chattanooga plant.

Gestamp, supplier of chassis and other large components, is a prime example of the VW supplier park strategy and the networking that takes place across the south-east. An anchor resident of the Chattanooga park, Gestamp also supplies a sub-frame for BMW’s operation in South Carolina. As the Atlas has joined the Passat on the production line in Chattanooga, VW officials say, the company has been able to reduce purchasing costs by attracting more suppliers into the Chattanooga area.

“In our ideal logistics concept, we want to have a certain quantity of big, complicated parts within a radius of five miles. These are components that are normally delivered just-in-sequence. Typically, it’s bumpers and seats – things that you cannot have in stock,” observes Roberto Eggeling, vice-president of logistics and production control at VW’s Chattanooga plant. “The next step is to say: would it be possible to have all the other suppliers within a radius of 200 miles. That would be our dream. We look at logistics as part of production and to bring in parts outside of that 200-mile radius has a greater cost.”

Part of VW’s evolving logistics strategy at the Chattanooga plant has been to lessen its reliance on national fleet resources, placing more of its transport needs on local and regional providers. Tranco Logistics, a Chattanooga-based warehousing and transport company with a fleet of 175 trucks, was introduced to VW through a 3PL. Tranco, which had the honour of making the first parts delivery to the Chattanooga plant, has continually built upon that early relationship with VW, learning its processes.

"I understand why Volkswagen prefers to work local. We can react faster, especially in Chattanooga. Our goal is to respond, respond, respond – be proactive to prevent issues and be reactive to issues that come up." - Bruce Trantham, Tranco

"I understand why Volkswagen prefers to work local. We can react faster, especially in Chattanooga. Our goal is to respond, respond, respond – be proactive to prevent issues and be reactive to issues that come up." - Bruce Trantham, Tranco

“One of the initiatives we’ve had in Chattanooga over the past few years is to develop local companies, and Tranco does a fantastic job for us,” explains Monteiro. “They started working with us on our bodyshop routes. We worked with them to understand our processes and the specific systems that we have, and that effort paid off because we found that we have more reliability from our local partners.”

VW, as part of its local production strategy, has also leveraged Tranco’s warehousing capacity. Tranco holds stock for three VW vendors, encompassing wheel and tyre, fuel tank and mirror assembly, and even carries out mirror assembly at its main Chattanooga warehouse.

“I understand why Volkswagen prefers to work local. We can react faster, especially in Chattanooga. Our goal is to respond, respond, respond – be proactive to prevent issues and be reactive to issues that come up,” notes Bruce Trantham, co-founder of Tranco, which was established in 1995. “We’re down in Birmingham 18 times a day. We’re in South Carolina. We make runs to the port of Savannah. Volkswagen has been very good for us, especially in [terms of] the pace at which we have been able to grow with them. We’ve learned so much about the automotive industry, and we’ve had other companies from automotive call on us. It’s amazing how it’s worked out.”

“The idea is to have one owner for the whole process. It’s about seeing the pros and cons,” says Eggeling about VW’s desire to build strong working relationships and a supporting network within close proximity of the plant. “It’s about putting things together and finding solutions that are better. While cost is always important, it’s most important to make sure that we are mitigating risks and not heading into a potential problem just to save some pennies.”

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)