Magna is putting an emphasis on global coordination, standards and best practice for both logistics and packaging, with technology and training crucial to the tier one’s future success

Magna is putting an emphasis on global coordination, standards and best practice for both logistics and packaging, with technology and training crucial to the tier one’s future success

A defining characteristic of large tier one suppliers is often decentralisation. At Canada-based Magna – North America’s largest tier supplier and among the biggest globally – operating units such as powertrain, seating, exterior or the body and chassis group are largely responsible for their respective businesses and hence their logistics and supply chain processes. That has historically meant nimble, flexible operations, but fewer possibilities to take advantage of the company’s scale in areas like logistics and purchasing.

In this story...

However, as this magazine has reported, in recent years Magna has made moves to align standards and sourcing decisions, particularly in Europe, where since 2005 the Graz, Austria-based Magna Logistics Europe – now renamed Magna Logistics – has been rolling out common procedures and systems in logistics tenders, packaging, contracting and planning (see Automotive Logistics January-March 2015). Klaus Iffland, vice-president of purchasing and logistics at Magna International Europe, points to a standardised sourcing process for logistics services that Magna Logistics introduced to reduce costs, but also to improve the company’s ability to make ‘total cost of ownership’ decisions about parts purchasing and manufacturing decisions.

“This has been highly appreciated across Europe, and is something that we want to strengthen and roll out further,” says Iffland, who oversees common purchasing of all parts, equipment and logistics in the region, responsibilities that Magna combined in Europe in 2011.

There is, however, still considerable power concentrated across Magna’s divisions and operations in Europe. Larger sites, such as the Magna Steyr vehicle contract manufacturing plant in Graz, or larger Magna Powertrain facilities, usually control direct supplier deliveries and in-plant handling, for example. Nevertheless, a trend continues towards Magna Logistics coordinating more tenders centrally across European operations and divisions, especially for common and international freight, while it has also been expanding its focus in planning, from packaging through to line feeding.

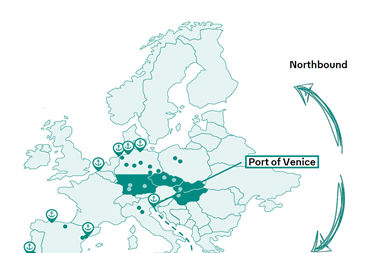

In some cases, Magna Logistics has sourced and implemented door-to-door supply chains across divisions, such as for parts out of Mexico into Russia (which are combined at a Magna Logistics-selected consolidation centre in Veracruz) or for material moving into Russia from Europe, albeit in very close interaction with the Magna divisions.

Over the past year, efforts to share common processes have begun to go global across Magna’s major regional organisations, with the establishment of global functions in logistics as well as in packaging. Magna Logistics’ director, Jörg Blechinger, has taken the lead for logistics, while Bridget Grewal, Magna’s packaging continuous improvement manager, based in Troy, Michigan, is leading packaging.

This coordination should not be mistaken for an overarching centralisation, as Magna’s operating groups and regions remain independent. However, these groups are coming together in something resembling a federation, with the focus on sharing relevant standards and best practices. Region-wide steering committees are being formed across divisions for logistics and packaging, as well as global steering committees in these areas.

“The objective is to have a global standardisation of commodities for both logistics as well as packaging, and a global lead link to find synergies and best practice,” says Blechinger. “In Europe we have already consolidated a lot of material and now have much more transparency. We now have an opportunity to do the same together with North America and Asia Pacific.”

Blechinger hopes to further develop regional organisations similar to Magna Logistics in Europe. In North America, for example, such a team would act as a common resource for tendering and planning across more than 150 Magna plants in the US, Canada and Mexico. Blechinger says he is already working with senior logistics leadership across Magna’s North American divisions, including John Begg, director of logistics and trade compliance for Magna Powertrain.

“John is working with me, together with representatives in South America and Asia Pacific, in a global steering committee for regular communication and strategy development,” says Blechinger. “We are also talking about rolling out Magna Logistics processes and standards in all Magna regions.”

There is already an effort to bundle sea freight tenders for European and North American plants, for example.

“This is the global link we are working on at the moment. The intention is to completely standardise the tariff structure for sea freight, so that we have the same terms and conditions, and the same contracts behind it,” says Blechinger. “We won’t do that all at once because it is too much, but we will roll it out in sequence.”

With this global approach, Magna will be able to consolidate more freight across regions, adds Blechinger. “In a global sea freight RFQ, we can look at getting parts out of Germany and consolidating them for dispatch to specific regions, like Brazil,” he says.

An effort to define global logistics and packaging standards mirrors earlier developments for Magna’s wider purchasing organisation, which has benefitted from centralised standards, processes, commodity groupings and leadership. “We started in Europe about ten years ago, and have since implemented a similar structure in purchasing in North America and Asia where we group volume by synergies, commodity codes, and do cross-group purchasing wherever it makes sense,” says Klaus Iffland.

Although the main focus is on processes, these approaches are having physical impacts across Magna’s supply chain, and are likely to increase in future. The purchasing alignment has influenced Magna’s global supply base for material and components. Next, Iffland sees opportunities for global indirect sourcing and non-production purchases, such as mobile phones or gas and energy, for example. He also believes there can be more common buying for plant and logistics equipment like forklifts, robots, cranes, or other machinery and equipment.

“In a decentralised world you risk to buy such equipment in small volumes, but it is up to us to find clever ways to get economies of scale,” he says. “For machinery, for example, much of the equipment is specific to what we are building in each plant, but since there are only a handful of players in the world for equipment like robots, you can still go to them and offer a combined business.

“It is a more powerful approach if you are buying five units, versus a few hundred across the company,” adds Iffland.

Blechinger and his team have pursued optimisations across the supply chain. Earlier this year, for example, Magna Logistics redesigned Magna’s material flow for Russia, moving from a consolidation centre in Chemnitz, in eastern Germany, that combined mostly German suppliers bound for Russia, to a centre in Liberec, in the northern Czech Republic, which brings together German as well as more central European suppliers, including from the Czech Republic.

Further logistics adjustments seem likely given some of the recent changes across Magna’s companies. For example, earlier this year the company finalised the sale of its interiors business (excluding seating) to Grupo Antolin; in the meantime, it is acquiring transmission supplier Getrag, as well as UK-based body pressings manufacturer, Stadco.

In 2016, Magna Logistics’ planning IT tool will be rolled out to include in-plant logistics and material handling, incorporating cost references and scenario planning for things like kitting, sequencing and kanban

In 2016, Magna Logistics’ planning IT tool will be rolled out to include in-plant logistics and material handling, incorporating cost references and scenario planning for things like kitting, sequencing and kanbanAt Magna Steyr, meanwhile, the plant will soon see several important model changes: Mercedes-Benz G-Class production has been extended, while BMW will end Mini assembly but add another model; Jaguar Land Rover will also start building vehicles at the plant in the near future.

Such changes will be integrated quickly into sourcing and planning procedures, with likely impacts for the supply base and logistics. “The integration of new companies always leads to opportunities created by higher volumes,” Iffland says. “And with supply and model changes, we foresee opportunities.”

Planning from external to internal supply chains

An important way in which Magna has been able to adapt to supply chain changes quickly in Europe has been through a planning IT tool that Magna Logistics introduced several years ago. The tool simulates logistics costs across dozens of variables and cost references, including transport mode, truck utilisation, time-window planning and freight rates.

Since this was introduced, its main focus has been on external logistics costs, such as inbound logistics transport. However, Magna is currently integrating in-plant logistics and material handling applications to support planning for the entire supply chain, from the production line back to suppliers, including layered planning and material flow like kitting, sequencing and kanban. This planning is being added to the software and will be rolled out in 2016.

Blechinger believes such total logistics cost modelling gives Magna a competitive advantage, as it can quickly demonstrate the logistics and handling implications of different supply decisions. While he and Iffland acknowledge that carmakers often direct tier suppliers’ sourcing decisions, Magna can present optimal alternatives.

“Although material purchasing is still the leading function, supply chain costs are becoming more important, with logistics playing a key role in sourcing decisions,” says Blechinger. “We are doing everything we can to get to a stage where we can provide fast information for the purchasing department. That is not easy if you have a bill of material for 1,000 parts, but our logistics planning tool helps us to calculate the difference that it makes from one supplier to another, and now will also incorporate the impacts in the plant,” he says. “We will be able to show carmakers a variety of alternatives down the tier supply chain.”

Iffland stresses that such planning is essential to making sure transport, packaging and inventory are properly considered in sourcing, along with a part’s piece price. “These considerations can often tip the balance in sourcing decisions between different locations,” he says.

Looking to risk as opportunity

As European production and sales rise steadily, Blechinger and Iffland are optimistic about Magna’s supply chain. However, they stress the need to adapt to new technologies and to train employees in line with the industry’s evolving needs. At Magna Steyr, for example, some forklift trucks are now being guided in plants by smart tablets. The company is also starting to use simulation software to plan and design production and material flow at the plant in Graz. Blechinger adds that Magna will start to use such systems to design and build warehouses. “This is only the beginning. In the future, logistics will not be able to survive without IT,” he says.

Such technological shifts are partly why Blechinger believes strongly in partnership with universities and academies to train employees across the supply chain. For example, at its recent Magna Logistics Days held in Austria, Magna Logistics ran an innovation workshop with its own managers and various logistics providers on topics related to sustainability across the environment, the workplace and in economics. The output of the workshop is being shared with partner universities to help inform their coursework.

“This is hopefully helping to train logistics managers and staff to be ready for future challenges,” he says.