Six months after Chery JLR’s Rui Zhu and Alex Holland gave an exclusive preview of their logistics plan to Christopher Ludwig, they invited him back into the plant shortly after launch to reveal the latest innovations for its complex material flows

Six months after Chery JLR’s Rui Zhu and Alex Holland gave an exclusive preview of their logistics plan to Christopher Ludwig, they invited him back into the plant shortly after launch to reveal the latest innovations for its complex material flows

A few weeks before visiting Chery Jaguar Land Rover’s new plant in China in late November, I happened to be at JLR’s flagship plant and headquarters for global material planning and logistics (MP&L) in Solihull, outside Birmingham in the UK. The plant has been at the centre of the carmaker’s huge growth in recent years and an impressive transformation had taken place in the two years since my last visit, including new halls for manufacturing and aluminium bodies, an expanded area for upcoming Jaguar assembly, and a brand new customer centre.

These days, the parallels usually drawn between industrial growth in China and Britain are in comparing China’s rise over the past three decades to Britain’s emergence as a manufacturing power during the industrial revolution in the first half of the 19th century. JLR’s global growth, however, is an Anglo-Sino success story, fuelling expansion in both countries. The Tata Motors-owned company has launched its first major overseas plant at the same time that it is investing in expanding production in the UK (not to mention other global locations), including a new engine plant in Wolverhampton that started operations this past autumn

- Logistics strategy preview – dawn of a new era

- Plant launches

- UK engine plant launches

- Logistics outsourcing – evocative logistics

See also

See also

- Importing parts to China

- Tier ones look to reusable packaging

There are, of course, differences to the shape of the growth in both places. While Solihull has removed some older buildings to make way for new, glistening silver halls, the new structures rise up amidst dark-coloured brick buildings – some of them ‘shadow’ factories that built munitions during the Second World War – which suggest an older, albeit still proud era in the country’s history.

Between the new and the old and in limited space, JLR’s manufacturing and logistics team perform near miracles to ensure the plant can meet its three-shift production schedule. To boot, the Solihull plant is landlocked, leaving even less room to expand. Logistics areas, for example, have increasingly been based at off-site warehouses.

On the other side of the world, the investment and expansion is also huge, if not seemingly limitless. In November, the 50:50 joint venture between Chery and JLR started production of a local version of the Range Rover Evoque (called the Aurora in China) with plans to add another Land Rover SUV and a Jaguar sedan by 2016, when the plant will reach its 130,000-unit annual capacity. The factory is at the cutting edge, from the design and layout of buildings to its capabilities. The bodyshop, more than 85% automated, will be able to build multiple different platforms, while its 700-metre conveyor to the assembly area is the longest in China, says Rui Zhu, director of MP&L at CJLR.

Perhaps just as impressive is the potential of the open space around the factory in the industrial zone of Changshu, 80km from Shanghai. The joint venture is already expanding with the construction of an engine plant on the site, due for completion in 2017. A new aluminium body shop, the first in China, is also under construction to support the introduction of new Jaguar products.

Planning material flow right from the start

The inbound and outbound logistics setup for the factory is diverse and unique in many ways for China (see box below), but it is within the factory that perhaps its most significant advances for material flow and handling are to be found. There are many best practices drawn from JLR, but like many manufacturers expanding in China, CJLR has had the advantage of a greenfield site without the UK’s space and building limits. This has allowed the joint venture to define processes that are relatively new for JLR’s logistics, such as a high level of kitting and the use of automated guided vehicles (AGVs) along a dolly line.

“Normally, everybody else in a plant wants to limit or take away the space for logistics activities, especially if they could be used by manufacturing,” he says, “but we have worked together to determine how much space we should really have for storage and to create a really effective material flow. We’ve done that upfront rather than to try to fit it in afterwards and it’s been a big advantage.”

An example of this design is the plant’s supermarket in the trim and assembly area, which is large enough to accommodate a range of kitting, sequencing and replenishment methods. In its logistics planning, the company has thus taken something of a different balance for line-feeding processes compared to other JLR plants, says Rui. Whereas in the UK a manual push-button kanban system is “fundamental” for triggering the delivery of parts to the line, for CJLR the main process for most small parts will be a scanning system that automatically sends a signal to the supermarket.

“While we use a number of methods, fundamental for us is auto-replenishment with auto-backflush,” says Rui. “More traditional kanban is used, for example, for big parts such as windows coming in one box, but that is more of a last resort.”

"While we use a number of methods, fundamental for us is auto-replenishment with auto-backflush. More traditional kanban is used, for example, for big parts such as windows coming in one box, but that is more of a last resort."

"While we use a number of methods, fundamental for us is auto-replenishment with auto-backflush. More traditional kanban is used, for example, for big parts such as windows coming in one box, but that is more of a last resort."- Rui Zhu, Chery JLR

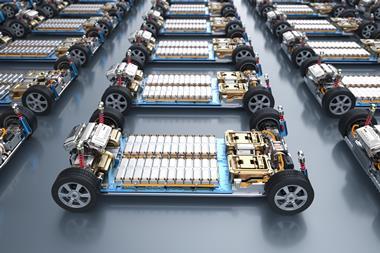

Similar to other plants, just-in-sequence deliveries are moved by conveyor systems for modules such as seats, wheels and tyres. However, another difference to JLR is a higher level of kitting and the dolly AGVs in place for the door line, and two trim lines. The AGVs follow a route marked along the floor, which also recharges them. Engines and transmissions will also eventually be moved to the line by AGV.

The plant currently builds four trim levels of the Evoque/Aurora, according to Holland. While the door line has a lot of parts and is thus effective for kitting, he also points out that it is less complex and constrained than production in the UK (the Evoque is built at the company’s plant in Halewood, near Liverpool), since CJLR is only producing vehicles for the Chinese market. “In the UK we export to 130 different countries, including right-hand and left-hand drives, and many different specifications,” he says. “You can easily have 250 different left-hand mirrors.”

The plant is nonetheless well equipped to manage the part and option complexity for the premium vehicles it will be building. In the supermarket, Anji-Ceva, which is responsible for in-plant logistics, will put together the kitting carts in sequence to the assembly line with a buffer of 30 minutes. In a first for Chinese plants, CJLR has a screen above the kitting area that closely monitors the assembly times against the kitting progress to make sure that the activities remain synchronised, a process known as ‘supply-in-line sequence’ (SILS). A pick-to-light system is also in place to guide workers to the right part.

The MP&L department has been responsible for developing a number of visual-aid innovations designed to better manage material flow and react to supply chain issues. One is the screen above the kitting area, which monitors the assembly flow in relation to kitting and helps maintain the SILS flow.

Another new approach is an airport-style arrival screen to manage deliveries from the warehouse to the plant’s ten gates. At many plants this might simply be a hand-drawn board displaying the scheduled time window for each truck. For CJLR, each gate is digitally displayed with the truck number and its scheduled arrival window, with a real-time status update on whether it is on time or delayed. “CJLR is the first carmaker in China to set out to manage dock operations in the same way as airport terminals are managed,” says Rui.

“Whenever a truck arrives to one of our gates, the screen shows which dock it will go into,” he explains. “We can then check whether it is free or still occupied; if it is occupied, we can prevent the truck from coming and waiting at the plant gate, and if it is free it can simply arrive and make the drop off.

“It also balances our manpower, space and workload,” Rui adds. The company has won an innovation award in China for this system.

CJLR also has a screen visualisation that displays the progress of outbound truck deliveries. Since all of CJLR’s carriers are set to have GPS monitoring, the outbound logistics team uses six, 60-inch (150cm) television screens that display the location of each truck over a map of China, including an estimate of whether they are moving ahead of or behind schedule. A smaller screen will also track quality and operational KPIs along the route. Trucks that are severely late or delayed will have a red line, indicating that an alternative method is needed.

Such approaches are simple, but effective methods of managing voluminous and complex logistics flow. Rui is proud of their development as they are unique to CJLR. “We are operationally focused here and don’t just manage operations at our desks,” he says. “We should be keeping a constant view of our activities, and be ready to respond.”

Improving global links

According to Rui, the company hopes to increase the amount of material moved to the line by AGVs. Doing that effectively, however, depends largely on the accuracy of the bill of materials (BOM), since the parts from containers and trucks have to match the local production schedule if the kitting and sequencing are to be effective.

At the moment, pinning down such BOM accuracy across an international supply chain can be tricky, whether it is over managing engineering changes or exchanging data. According to Holland, CJLR needs to “bed in” such processes and further prove the data accuracy across a variety of systems and supply chain steps to ensure stability, with a longer term view of increasing the use of kitting and AGVs in the factory.

Of course, CJLR does not have to reinvent the wheel of car production or logistics, no more than China had to start a new industrial revolution where Britain and the rest of the world left off. AGVs may be rare in JLR production, for example, but they are more common in new Chinese plants with increases in automation. Supply in-line sequence and kitting are also not new – the Qoros factory across the road from CJLR kits almost all of its parts – but the company has looked to simple, innovative improvements, such as the time window display screen.

These developments are significant as JLR looks to expand globally, whether in already announced plants in Brazil and India or elsewhere. While the scale of growth in China and the speed at which development and construction is possible may be tough to match, planning an effective internal material flow well in advance is a lesson that the company is likely to export from Changshu.

Unlike other joint-venture carmakers in China, in which an incumbent provider owned by the Chinese OEM tends to have principal responsibility for logistics, CJLR has contracted directly with domestic Chinese, joint venture and foreign providers.

As previously reported in the July-September issue of Automotive Logistics, CJLR has divided its inbound supply chain between two lead logistics providers. Rui Zhu reveals that China-bound material from Europe is handled by Chinese freight forwarder Sinotrans, while Anji-Ceva, a joint venture between SAIC Motor’s Anji and Ceva Logistics, is responsible for domestic supplier deliveries, warehousing and in-plant logistics.

Much of the supply chain for the Evoque, whose mother plant is in Halewood, UK, is rooted in Europe. For this leg of the chain, DHL Supply Chain, under contract with JLR, collects and consolidates European and UK material, delivering it to an Export Sales Centre in Hams Hall, near Birmingham. Logistics provider syncreon runs this centre, with responsibility for packing and consolidating the material into sea and air freight shipments (syncreon has also recently started as JLR’s in-plant logistics provider at its new engine plant in Wolverhampton). Material is then handed over to Sinotrans for onward transport to China, says CJLR’s Alex Holland.

The material moves from the port of Felixstowe to the port of Shanghai, where Sinotrans transfers containers for temporary storage and the onward journey of some 80km along the Yangtze River by barge to the inland port of Changshu – a transit time of about a day – before trucking them to the plant.

Sinotrans hands over material at a deconsolidation centre over the road from the plant, where Anji-Ceva takes over responsibility. The centre includes three warehouses for imported material, domestic inbound and spare parts; there is also space dedicated to empty returnable packaging for domestic suppliers. Anji-Ceva manages the warehouses along with the domestic milkruns and empty returns for local suppliers.

Rui expects the deconsolidation centre to receive around 105 trucks each day as production starts in earnest in 2015, rising to 130 the next year. Once material is unpacked and sorted for plant docks, Anji-Ceva is expected to move around 150 trucks per day from the centre over the road to the plant gates, growing to 180 trucks in 2016.

While imported material is high, at least in the initial production phase for models in Changshu, supplies such as seats, windows and wire harnesses have already been localised. Most of the domestic material will arrive by milkrun, which will run at “full scale”, according to Rui. Direct deliveries to the plant are mainly for just-in-sequence material moved to the line by conveyors, such as seats, bumpers, tailgates, wheels and tyres.

CJLR has opted to use the same LLP for inbound deliveries and in-plant logistics operations, so Anji-Ceva is also the on-site supplier for the plant docks, its large supermarket and kitting area, and line-side material feed.

According to Rui, a next step would be to open export channels that can move material directly to China rather than being consolidated in the UK. Together with JLR, the company is establishing an export centre in Germany, from which material from mainland-European suppliers can be shipped.

“In this way, the joint venture takes on more responsibility, can avoid double handling and reduce lead times,” Rui says.

Insisting on outbound quality

CJLR’s outbound logistics setup also uses multiple providers. Changjiu Logistics, a privately owned company, will manage operations at the plant’s 2,000-vehicle capacity yard, which should be finalised in early 2015.

Changjiu is responsible for about 75% of vehicle distribution, while NYK Automotive Logistics China will handle the rest. “We chose Changjiu, the second largest player in outbound after Anji in China. NYK is also very famous in this area,” says Rui.

"As the first international factory for JLR, we have to make sure that the delivered quality is every bit as good as that from the UK. We are not going to compromise our brands by using illegal and dangerous trucks." - Alex Holland, Chery JLR

Outbound logistics in China can be messy, especially with the use of oversized and non-standard trucks carrying as many as 25-30 vehicles. For CJLR, however, there can be no question of sanctioning the use of illegal trailers.

“We are insisting on legal trucks for both inbound and outbound logistics,” says Holland. “As the first international factory for JLR, we have to make sure that the delivered quality is every bit as good as that from the UK. We are not going to compromise our brands by using illegal and dangerous trucks.”

According to Rui, CJLR worked with JLR’s UK management to audit and bid for providers, train the local team and adopt global standards, including protection products. CJLR’s technical requirements allow standard, covered trucks to carry no more than 8-10 cars and Rui expects providers to comply. CJLR vehicles can be combined with imported JLR vehicles (NYK is a provider for both), but not with other brands. “The quotations providers made were based on our technical requirement, so there should be no reason to deviate from them,” Rui says. “The carriers have signed contracts and are expected to deliver at that quality level. Anything else would be in violation of our agreement.”