In recent years, Russia has put considerable resources into encouraging recovery in its domestic automotive industry. Last year, the federal budget included 62.3 billion roubles ($1 billion) in state aid for carmakers. Such sums have been spent primarily on boosting demand in the domestic market, which has been under pressure since 2014 due to a mix of factors, including international sanctions, the fall in global oil prices and structural problems in the national economy.

But a new development strategy for the Russian automotive industry, adopted by the government in May this year and covering the period to 2025, has apparently abandoned this policy, setting no targets on domestic demand. Instead, it places a new focus on exports, which the government wants to see nearly tripled in the next seven years, from last year’s figure of 83,400 units to 240,000 units in 2025.

The move is not unexpected. Speaking in late 2017, industry and trade minister Denis Manturov confirmed that Russia was going to cut direct funding for industries in which solid growth was evident, and that several national programmes aimed at supporting demand for light passenger vehicles in the domestic market would be scrapped this year.

Instead, Manturov said, the government would issue 100 billion roubles between 2018 and 2021 to support non-oil and gas exports. This sum was to be allocated to export projects in the aviation, special machinery and automotive sectors.

The total number of roubles incorporated in the Russian federal budget in 2017 for state aid to carmakers, equivalent to $1 billion

It is believed, however, that targets for component export will be comparable to those for finished vehicles, not least as the Russian authorities have been encouraging the export of both vehicles and components by OEMs with plants in Russia since 2017.

“The Russian government introduced subsidies to reimburse the costs of [automotive] product delivery for export in decree No. 496, adopted on April 26, 2017. This measure was designed both for finished vehicle manufacturers and automotive components manufacturers,” confirms Wilhelmina Shavshina, legal director and head of foreign trade regulation at DLA Piper. “It is important to note, however, that this set an upper threshold of transport costs on which the subsidies can be allocated.”

Raising export requirementsWithin its industrial assembly policy to date, Russia has provided state support only to OEMs meeting a particular localisation rate on components for their manufacturing operations in Russia. The industrial assembly agreements it has in place with most OEMs are scheduled to expire in 2019, however, and Russia has recently indicated that no fresh industrial assembly agreements will be put in place from July 1 this year.

Many now expect any new agreements – which from next year are scheduled to come in the form of so-called Special Investment Contracts (SPICs) – to feature particular levels of exports in their requirements for attracting state support.

[mpu_ad] Export levels are certainly likely to become of greater importance, says Shavshina. “We do not tend to think that export supplies will be the main condition for the reimbursement of import duties [on automotive components for assembly plants in Russia], but it may be a certain factor in the amount of reimbursement within state support measures for holders of both industrial assembly agreements and SPICs,” she says.

However, state support for automotive exporters will not be limited in future to breaks on the duties applied to automotive components imports.

Pavel Burlachenko, director of the automotive export department at the Russian Export Centre, the state export support body, says there are many other forms of assistance already available.

“One of these is credit and insurance guarantee support from the Russian Export Centre, provided at preferential rates compared with the market rate of bank borrowing. There are also special support programmes on the transport of products to export markets, including on certification, R&D and patenting,” says Burlachenko.

Tax breaks are a particularly important part of state aid, he adds, such as those that apply to VAT and excise duty in relation to exports of finished vehicles and automotive components. The Russian Export Centre stands ready to provide consultancy services to carmakers thinking of launching export supplies, he says.

Thanks to the various support measures, exports of vehicles and components are expected to be worth some $7.8 billion a year from 2025, according to Burlachenko.

Number of vehicle exports the Russian government wants to see taking place by 2025 – a near tripling of 2017’s 83,400

“Government support for export activities is essential at the moment for the Russian automotive industry,” she says. “This support is of great help to Russian OEMs, such as Sollers and Gaz, especially in terms of homologation and logistic costs.

“For global OEMs, however, decisions about vehicle exports are based on other arguments – subsidies do not really play any important role in the decision-making process,” she continues. “Another, maybe much more important consideration is trade relations and trade agreements with other countries. This is where the Russian government could support the automotive industry much more.”

Dependent on OEM strategiesIt is quite clear that in the coming years, Russia wants to become a major exporter of automotive products globally. What is not so clear, however, is whether foreign OEMs are willing to make their Russian production operations more central to their global supply chains.

“Only one international OEM considered Russia as a production hub for European buyers [in 2017] – that was Volkswagen, which exported 15,600 Skoda Yetis to central and western Europe. And VW Group did this mainly due to the capacity shortage in Kvasiny, in the Czech Republic,” says Hristova. “On the other hand, the fact that VW decided to export vehicles from Russia at all confirms, once again, that local assembly facilities comply with the highest requirements of global OEMs and that low vehicle exports from Russia are mainly related to the fact that global markets are already very well covered by different production plants.”

With the end of production of the Yeti in Russia in February, however, even exports by VW ground to a halt.

“As a result, exports will slow down significantly,” says Hristova. “We do not expect any other OEMs to export finished vehicles as actively as VW did last year. Increasing exports by the Gaz Group and Sollers will barely compensate.”

The upshot, she says, is that total vehicle exports from Russia are unlikely to rise any time soon.

“In terms of our expectations, exports totalling 5% of overall production in Russia [compared to 5.8% in 2017] would be a very good result in the short term. And anything higher will be barely achievable,” she says.

Any growth in export supplies from Russia will certainly be welcomed by ports, shippers and international logistics providers active in the country.

“For logistics providers, outbound logistics in support of carmakers in Russia is becoming an important area of business development. For shipping lines, it is even more important. Growing exports of finished vehicles will let ro-ro carriers secure additional loads on the way back from Russian and Baltic ports,” confirms Dmitry Vostrikov, MD of WWL Russia.

“Our company is actively supporting carmakers in Russia in development of the most efficient outbound logistics solutions using a wide network of ro-ro transport to various countries. We already have positive experience of several projects by Russian manufacturers and we expect to further increase our portfolio of clients,” he adds.

Such movements are likely to be both to traditional export markets and new ones, states Vostrikov.

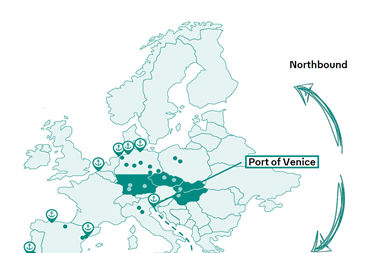

“Traditionally, the CIS countries have been the main markets for Russian carmakers – primarily Kazakhstan and Belarus – as well as some European countries, like Germany, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Italy,” he explains. “Historically,Cuba has also been and remains a big market for Russian manufacturers.

“At the same time, there are a number of regions that have good potential for export growth – like the countries of Latin and Central America, North Africa, some countries in the Middle East, Iran and South-East Asia – primarily the Philippines and Vietnam. Components are most likely to be exported to countries in which Russian manufacturers have set up local assembly or production facilities.”

Anna Komarova, head of the finished vehicle logistics department at Gefco Russia, says automotive exports from the country showed strong growth in 2017 and the trend was expected to continue this year.

“The state support programme, with the new initiatives approved in 2018, is the crucial factor [in terms of exports]. But there is also a positive effect being generated by the more competitive cost base for vehicle assembly in Russia compared to Europe, which is encouraging carmakers to make the most of their existing capacity in the country,” she says.

“Multimodal solutions including sea and rail are attractive options for exports, as there is a shortage of road transporters in Russia even for domestic work which can only be exacerbated by their use for greater export flows,” adds Komarova.

Andrey Novikov, deputy marketing director for Phoenix, the managing company for the Port of Bronka (through which exports of Hyundai and Kamaz vehicles flow), says the main problem in exporting more finished vehicles through the ports will be the storage space required, though this isn’t a particular problem at Bronka itself.

“Two finished vehicles occupy the place of five [stacked] containers,” points out Novikov. “But we are 100% ready to cooperate with automotive plants in Russia.”

Outside the Czech Republic, the biggest export destinations last year for Russian-built vehicles were Ukraine, at 3,800 units; Latvia, at 3,500; and the UAE, at 3,000. Other export markets last year included China, Hungary, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan and Lebanon, according to Timerkhanov.

“It is difficult to say what will happen in future. But whatever the case, Russian OEMs remain interested in new markets and will continue developing exports. Still, [demand in] our domestic market has not yet reached the pre-crisis levels and it is not clear when they will be reached, while assembly plants in the country are only running at about half their design capacity,” says Timerkhanov.

Carolina Demenko, a spokeswoman for VW, says carmakers have also been developing component exports.

“In 2017, the company exported 7,000 blocks of Russian-made cylinders to the engine manufacturing plant in Mladá Boleslav, in the Czech Republic,” Demenko says.

“In early 2018, meanwhile, Volkswagen Group Rus signed an agreement with the Federal Customs Service of Russia on support for exports – and this year, the company plans to export 40,000 1.6 MPI engines from its Kaluga assembly plant to production sites around the world, including the European ones, as well as exporting 10,000 Skoda Octavia vehicles from Nizhny Novgorod to the EU.”

“In early 2018, meanwhile, Volkswagen Group Rus signed an agreement with the Federal Customs Service of Russia on support for exports – and this year, the company plans to export 40,000 1.6 MPI engines from its Kaluga assembly plant to production sites around the world, including the European ones, as well as exporting 10,000 Skoda Octavia vehicles from Nizhny Novgorod to the EU.”

Component exports have been growing for several years in Russia, with several major manufacturers getting increasingly engaged in such operations, adds Alexey Beliyev, sales manager at Faurecia Russia.

“Faurecia has been developing exports for several years, though it has been far from easy. Components exports from Russia have always been low, only accounting for 2% of domestic production. But there has been strong progress in this direction recently,” says Beliyev.

“This is because the Russian finished vehicle market has overcome the 2014-2016 crisis and is now recovering steadily. Moreover, many carmakers have started adjusting their operations in accordance with the country’s development strategy for the automotive industry, which in many respects aims to boost exports.

“Faurecia Russia exports to Romania and Uzbekistan. Export options are being also developed for the countries of the Middle East, Latin America and Africa. Business with these countries is not easy to establish, but according to our forecasts, the growth in export supplies will be significant,” adds Beliyev.

Analysts also believe that Russian carmakers, including Gaz Group and UAZ, owned by Sollers, could make strong progress in promoting their products on the international market in coming years.

“Sollers and the Gaz Group have accumulated a lot of experience in the past couple of years and started exports to several new countries. For now, we don’t see a lot of their vehicles in global sales statistics but we expect to see increased sales of the Gaz Gazelle and UAZ Patriot in South America, the Middle East, Africa, and some countries in south Asia,” says Hristova.

However, Gaz Group’s export potential, in particular, could obviously be affected by recently imposed US sanctions on a number of Russian businessmen including the company’s owner, Oleg Deripaska.

The incentives may be in place and the production capacity may be there, but whether Russia’s vehicle manufacturers will truly be able to meet the government’s target of tripling total vehicle export numbers by 2025 is by no means certain.