Market analysis: an increase in regional manufacturing is changing South Korea’s export production while premium imports become more popular within its borders

Market analysis: an increase in regional manufacturing is changing South Korea’s export production while premium imports become more popular within its borders

With a relatively small domestic market, South Korea’s automotive industry remains highly export focused. According to Tsukasa Watanabe, lead analyst for Asia Pacific at PwC Autofacts, the ratio of production for exports remains above 65%, much higher than the 45% currently seen in Japan. That makes the industry more vulnerable to localisation, he says.

In this story...

Such localisation is well underway as Hyundai and Kia enter another phase of aggressive global investment following several years of frozen capacity. In China, after Kia added a third plant last year, Hyundai’s joint venture will build two new plants by 2017. By 2018, on current announcements alone, the Hyundai brand will have the capacity to build around 3.8m vehicles outside South Korea, or twice the level it builds at home. After Kia completes a new factory in Monterrey, Mexico next year, it will have at least the same annual production capacity in its overseas factories – 1.7m units – as it does in South Korea.

While China tends to build for its domestic market, analysts suggest that capacity expansion in North America, the top destination for South Korean light vehicle exports, will likely divert flows from South Korea. “Expansion in North America can affect South Korea’s exports to the region, especially for small and compact vehicles such as the Kia Rio, Forte or the Hyundai Accent,” says Ian Park, senior analyst for Korean vehicle production at IHS Automotive. “We expect Hyundai-Kia will try to offset the output loss with newly added vehicles like hybrid and premium cars, but it will be limited in its ability to catch up all the volume.”

While the Korean won’s appreciation against the US dollar since 2008-2009 has influenced production, a lower Japanese yen may be an even thornier problem for South Korean OEMs as they compete directly with Japanese brands abroad, especially in North America. This competition has heated up even further in 2015, with Hyundai and Kia lagging behind several Japanese brands in the US. “That is one of the reasons Hyundai is carrying out a co-location strategy in North America to lower exchange risk,” Park says.

Another reoccurring issue in Korea, which now appears to be having long-term effects, has been labour disputes. While these disputes have pushed up wages, probably the bigger problem has been their wide disruptions to assembly. Watanabe points out that annual strikes during the summer have been particularly damaging for exports to the US market.

Another reoccurring issue in Korea, which now appears to be having long-term effects, has been labour disputes. While these disputes have pushed up wages, probably the bigger problem has been their wide disruptions to assembly. Watanabe points out that annual strikes during the summer have been particularly damaging for exports to the US market.

“Hyundai Motor, GM and others tend to lose production in June, July and August from strikes, which is very, very bad for exports, especially to North America,” he says. “In the US, the new model year starts in October, which means that for Korean-built models to reach showrooms in time, they need to be built in July or August.”

Even this year, signs of new flow patterns continue to develop. With Kia launching sales in Mexico, for example, ahead of a plant launch next year, it has begun initially to import models to the country from Europe and the US.

While North American localisation is a threat for South Korea’s production base, developments in other regions are also significant. The country’s second largest export market is the Middle East and Africa, where it shipped 677,000 cars last year. Watanabe points to a medium-term risk should Korean OEMs build local plants or use those in India or Europe more to serve the region, for example.

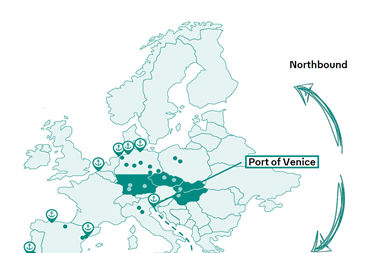

Europe has already seen the most shifts in exports, with more changes underway. In 2005, Korean exports to the European Union and Russia were more than 1m units; by 2014 they were around 400,000 units despite higher overall sales for Hyundai-Kia, whose plants in the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Turkey, and Russia have met most local demand growth.

While Hyundai-Kia has benefitted from localisation, the drop in European exports has squeezed GM’s South Korean base. According to Park, Chevrolet in Europe and Russia accounted for about 44% of GM Korea’s exports in 2013.

Although the carmaker has recently begun South Korean output of the Opel Karl/Vauxhall Viva for Europe, it is not enough to offset volume losses. GM Korea’s 629,500 finished vehicle exports in 2013 dropped to 476,000 in 2014. In the first five months of 2015, exports were down a further 10.4% compared to last year.

This fall is partly explained by the Russian market, which has been a drag on all Korean exporters; Ssangyong suspended shipments to Russia starting from January, for example. However, GM has seen a wider shift from its plants in South Korea, says Park, which are no longer low cost across GM’s global network. GM Korea is also seeing competition from neighbours. The president of GM International Operations, Stefan Jacoby, recently admitted India will likely be a big growth engine in Asia, and that GM Korea must find ways to “drive efficiencies over time”.

This fall is partly explained by the Russian market, which has been a drag on all Korean exporters; Ssangyong suspended shipments to Russia starting from January, for example. However, GM has seen a wider shift from its plants in South Korea, says Park, which are no longer low cost across GM’s global network. GM Korea is also seeing competition from neighbours. The president of GM International Operations, Stefan Jacoby, recently admitted India will likely be a big growth engine in Asia, and that GM Korea must find ways to “drive efficiencies over time”.

“We expect GM Korea’s role as an export hub to diminish so it should concentrate capability more on the domestic [Korean] market and other export regions like the Middle East, Oceania and East Asia,” Park suggests.

GM’s changes have had a significant impact for Höegh Autoliners, which built much of its South Korean service around the carmaker, according to Trond Sjursen, head of commercial at Höegh.

“We retracted our service levels quite a lot compared to what we used to run out of Korea into Europe 2-3 years ago, which is almost entirely because of the GM decisions,” he says. “For example, we had signed a contract with GM for what we thought were going to be big volumes into Russia and Ukraine, and you know what has happened – that is basically nothing now.”

For Hyundai and Kia, exports out of South Korea have been far more stable than for GM, however over recent years they have levelled off. After surpassing 1.2m in 2011, Hyundai’s exports out of South Korea declined marginally to 1.195m in 2014, while Kia’s 1.24m exports last year represented a mild growth in that period. However, the drop in Russia this year, along with rising vehicle inventories in the US – where Hyundai has largely missed an SUV boom – is also weighing on exports. In the first five months of 2015, for example, Hyundai Motor exports from South Korea declined 6.6% year-on-year to 490,375 vehicles. Kia’s South Korean finished vehicle exports are down 8.9% to 503,665.

Craig Jasienski, president and chief executive officer at Eukor, which carries 60% of Hyundai-Kia exports, admits the export market out of South Korea in 2014 and 2015 has been sluggish overall. “It is a toughening export market, whether for autos, high-and-heavy or other cargo types,” he says.

Macroeconomic and geographic shifts are changing the South Korean vehicle and logistics industries. But it is not a simple story of diverted flows. At Hyundai and Kia, the emphasis is increasingly on higher value cars rather than ramping up volume at Korean plants, while also developing alternative fuel technologies, including electric and fuel-cell vehicles (which Hyundai recently launched in the US). This focus on research and development is demonstrated by Hyundai’s plans for a new headquarters in the Gangnam-gu area of Seoul.

“Recently, Hyundai Motor Group spent about $10 billion dollars to purchase land in the centre of Seoul, where it is planning to build a global business centre to reinforce headquarter competency and expedite its path towards being a premium brand,” says Park. The new headquarters will eventually house Hyundai, Kia and subsidiaries including Hyundai Glovis.

However, the South Korean domestic vehicle market may no longer be the test bed for homegrown technology it has long been. Following changing consumer preferences and free-trade agreements with both the US and the EU, South Koreans are buying more imported vehicles. According to PwC’s Watanabe, the share of imported vehicles in the passenger car market, which has historically been around 2% or less, jumped to 14% in 2013, and to 18% in 2014, breaching 20% in the opening months of 2015. With South Koreans simultaneously demanding higher quality and confronting rising costs among domestic brands, premium shoppers are buying foreign, especially German brands, which have risen more than six-fold between 2008 and 2014.

However, the South Korean domestic vehicle market may no longer be the test bed for homegrown technology it has long been. Following changing consumer preferences and free-trade agreements with both the US and the EU, South Koreans are buying more imported vehicles. According to PwC’s Watanabe, the share of imported vehicles in the passenger car market, which has historically been around 2% or less, jumped to 14% in 2013, and to 18% in 2014, breaching 20% in the opening months of 2015. With South Koreans simultaneously demanding higher quality and confronting rising costs among domestic brands, premium shoppers are buying foreign, especially German brands, which have risen more than six-fold between 2008 and 2014.

“This comes from a change in mindset from the nationalist attitudes of the past, but it is also a challenge to the increase in prices for Hyundai and Kia vehicles,” says Watanabe. “If there is not much of a price difference in the high-end models, Korean people are buying the foreign brands.”

The bigger picture

Despite these developments, the overall picture is far from calamitous in South Korea. Overall, IHS sees Korean production and exports declining only slightly this year, and remaining stable or falling slightly for several years. At PwC, Watanabe expects output to be broadly flat for the near future.

Hyundai and Kia are not expected to erode their South Korean bases, even if exports decline somewhat. For other brands, exports are still climbing: Renault Samsung, for example, now builds the Nissan Rogue as an extra supply source for the North American market. The carmaker’s overall exports rose 26% in 2014 to nearly 90,000 units, and have grown more than 80% in the past six months.

Hyundai and Kia are not expected to erode their South Korean bases, even if exports decline somewhat. For other brands, exports are still climbing: Renault Samsung, for example, now builds the Nissan Rogue as an extra supply source for the North American market. The carmaker’s overall exports rose 26% in 2014 to nearly 90,000 units, and have grown more than 80% in the past six months.

Eukor’s Craig Jasienski notes that continued strength in the South Korean market and its brands has helped drive the shipping line’s business, including surprisingly brisk trade from Europe to Korea for imports, as well as strong export trade to regions like South America in recent years.

“[In 2014] we were, in the end, positively surprised how Korean manufacturers have managed to maintain competitiveness through smart products and production,” he says. “Increased competition will further sharpen products and services, and we think we’re in the right place to benefit and take part in these developments.”

For GM, even on a diminished scale, Korea remains an important export hub, where it maintains teams for shipping bids to support its purchasing team in Detroit. Sources suggest GM is already looking at ways to make its supply chain more efficient, including more direct ocean shipments. In particular, executives are hoping the South Korean government will support labour reforms, including more flexibility in putting workers on layoffs when production is lowered.

There are also positive tales in the domestic market. Though relatively small, it has grown steadily to around 1.45m units, and saw its best ever performance in the first quarter of 2015, and reasonable growth in the first six months compared to 2014. Kia, Ssangyong, Renault Samsung and import brands have reported particularly strong sales. GM has also had some success in recalibrating towards domestic sales. Watanabe suggests the total market could expand to 1.7m vehicles this year, though demographic trends suggest this is probably nearing its peak.

While South Korean exports will remain fairly strong, several emerging regions may soon surpass them. Mexico, which exported 2.6m light vehicles in 2014 and could reach 2.8m this year, may move in front of South Korea by the end of the decade or sooner. India, depending on its economy, could also build more cars than South Korea by 2020.

Already there have been some changes in global ocean services to reflect such developments; Höegh recently started carrying GM exports from India to Mexico, for example, and has gained a contract to move Buicks from China to the US, while the shipping line is also carrying more Hyundai-Kia volume, via Glovis, from the carmakers’ plants outside Korea, says Sjursen. The status quo, it would seem, is starting to change.

Click here to read the full list of stories in this special section.