As OEMs accelerate their EV programmes, there is growing concern that demand for battery materials will outstrip supply. Gavin du Venage considers the risks

Environmentalists hope that a transition to electric vehicles (EVs) will secure cleaner air in the near future and carmakers are putting increasing resources into electrification, but few people supporting the rise of EVs consider the viability of the raw material resources being fed into the lower end of this new type of automotive supply chain. These include the minerals – copper, nickel, cobalt, graphite and lithium – that are extracted in diverse parts of the world such as China, Africa and South America before being processed for use in EV components including lithium-ion (Li-on) batteries.

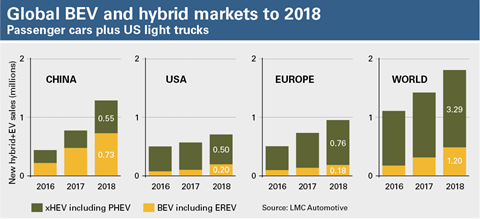

However, a logistical choke point is looming. While sales of EVs are on an upward trend, reaching 4.5m units worldwide in 2018 compared with fewer than 3m in 2016 (see graph on opposite page), the mining of raw materials is lagging behind. Considering that a single Tesla Model S, for example, has a 100kWh battery pack containing 8,256 cells, it is easy to see how the situation could greatly escalate.

While Tesla itself has not reached the level of sales it has hoped for, EVs have become increasingly popular with environmentally conscious motorists. Yet, it is not often taken into account that the reason the good old internal combustion engine vehicle was so successful was that it depended on readily available materials: iron ore and coking coal for steel, rubber and, of course, petroleum.

Now, OEMs are having to consider an entirely new logistics chain to support production, especially where the batteries are concerned. ‘Gigafactories’ that mass produce batteries are now appearing all around the globe.

“In 2015 there were three gigafactories globally; today we are tracking 75,” says Andy Leyland, head of forecasting at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence in London, and a specialist in battery minerals.

The factory frenzy comes as around 20 major cities worldwide have announced plans to ban gasoline and diesel cars by 2030 or sooner.

“There are very real risks that the electric vehicle revolution will be derailed by raw material shortages and price spikes over the coming years,” Leyland explains.

Coming a cropper

According to the International Copper Study Group (ICSG), EVs require three times the amount of copper than those powered by internal combustion engines. The metal is needed in the electric motor itself, as well as for connections between it and individual battery cells – up to 6km of copper connections in all, the ICSG says. Measured by weight, a fully electric car has around 80kg of copper, a hybrid needs 40kg and an average petrol-powered car uses about 20kg.

The ICSG predicts that, in the next decade, global copper demand will increase by 3-5m tons. In the long term, says the group, demand could reach 11m tons of new copper production for EVs alone.

The global copper market posted a surplus of 40,000 tons through the first two months of 2019, says CRU Group, a commodity analysis firm in the UK. However, the organisation notes that production also fell 1.8% over the first two months compared with the same period in 2018. Chile, the world’s top copper producer, saw its mine production fall 6% during this time.

CRU Group expects copper supply to be short of 41,000 tons by 2021 and 270,000 tons by 2023. This could mean another commodities super-cycle, with price increases in the double-digit percentages.

“We expect a bit of supply slowdown and stronger demand,” says Paul Robinson, director at CRU Group. “And yes, this does take recycling into account.”

Of course, more mines can be built. However, few operations are less popular with the public than mining, which is one reason why they often take place in jurisdictions where civic engagement is low, principally Africa, South America and China. Even then, mines cannot guarantee that they will not face public resistance.

And this is just copper; the supply chain for EV battery materials gets even more complicated when some of the less common minerals, such as cobalt, are considered.

Cobalt the biggest concern

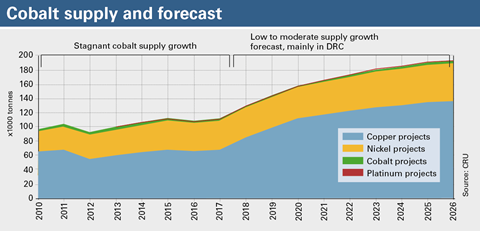

Tony Southgate, head of strategic marketing at Eurasion Resources Group (ERG), which is developing the $1 billion Metalkol cobalt project in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), says the African country will remain the world’s primary supplier of the mineral for years to come.

Metalkol will be one of the few primary cobalt mines in the world, as most of the current supply is produced as a by-product of copper mining. “More than 60% of cobalt starts its life in the DRC; that’s only going to increase,” says Southgate. In time, it is predicted that 80% of global supply will originate in the country, due to its large reserves. “Unfortunately for the rest of the world, this means most of the new supply of cobalt over the next ten years will come from the DRC,” he adds.

The DRC is one of the world’s poorest countries, and among the least stable. Mines have to provide their own security, electricity, water and other basic amenities. Furthermore, the threat of military conflict is constant, raising the risk of supply chain disruption. At the same time, corporate consumers of these metals are coming under pressure to ensure that their metals are sourced ethically. This is rather difficult to do when artisanal miners send children into hand-dug pits to secure coveted minerals.

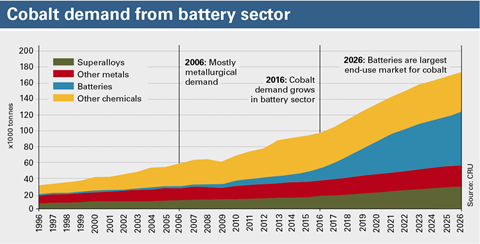

At the moment, total cobalt demand was around 125,000 tons last year, roughly in line with supply, according to Global Energy Metals Corp, a specialist investor in battery-related metals based in Vancouver, Canada. Back in 2016 demand was said to be increasing at a rate of 30% per year and but according to GEMC’s CEO and director, Mitchell Smith, the cobalt market will roughly double in size over the next decade, underpinned by demand for cobalt in electric vehicles.

”While the market is currently sufficiently supplied, we believe that over the medium term new mine and refined capacity will be required if supply is to meet demand, and that a diversified source of supply is required so that the world is not solely reliant on byproduct supply from the DRC,” he said.

CRU Group’s Robinson backed the point up: “The consensus is that cobalt availability is the biggest raw material concern when it comes to battery production.

Viability of deposits

To be clear, the logistical challenge presented by these metals is not about scarcity; the real challenge is to find them in bankable quantities. A useful analogy is the fate of South Africa’s gold industry, once the largest in the world.

From being the number-one producer of gold for most of the 20th century, the country is now barely clinging to eighth place. Yet it still has the world’s largest deposits of gold. The problem is, most of it is kilometers underground and the cost per ounce of mining it would exceed the gold price on the open market. As a result, mining companies are heading elsewhere in Africa, as well as to Australia and Canada.

“Mines ‘live or die’ on the quality of their resource,” says Peter Major, director of mining at Cadiz Corporate Solutions in Cape Town, South Africa. “The first question anyone will ask when a miner comes looking for finance is, ‘what is the quality of the resource?’,” he says.

In other words, it is not enough for there to be traces of a mineral in the ground; it has to be of sufficient quantity and quality to justify the $100 million-plus it will take to build a mine and the processing plant to separate the mineral from the waste rock in which it is found.

Mining has not changed significantly over the past 100 years, in fact. “At the end of the day, it is about breaking rocks and putting them through a chemical process to extract the mineral you want,” says Alistair McFarlane, president of the South African Institute of Mining and Metallurgy in Johannesburg, South Africa. “This is done mostly with explosives to break the earth. We need to develop non-explosive methods that are cheaper if we are to mine ultra-low-grade deposits.”

Mining companies know these issues all too well, but it is unclear whether automotive OEMs are as familiar with this side of resource production. Volkswagen, for one, has been ploughing increasing resources into its electrification programme as it seeks to put the embarrassment of ‘Dieselgate’ well behind it.

In 2017, the OEM tried to secure long-term contracts for cobalt and its representatives sat down with major suppliers such as Swiss commodities firm Glencore, but talks collapsed when VW’s initial price offers fell far short of the miners’ expectations.

The Financial Times quoted Glencore CEO Ivan Glasenberg as saying he would not agree to long-term fixed contracts during a period when the cobalt price was rising fast: “There are a lot of customers who want to lock in a supply, but naturally we will keep the price floating.”

Glencore is one of the largest cobalt suppliers in the world, with just one of its mines in the DRC supplying nearly 20% of global demand, and it has a diverse client base; automotive companies must fight for these resources alongside tech giants such as Apple, which uses them for its electronic products.

China challenge

Another complication in securing resources to support EV production lies in global politics. China, for instance, is the world’s largest supplier of rare earths – 17 minerals that are used in modern electronics.

Former Chinese premier Deng Xiaoping noted the strategic value of the country’s deposits as far back as 1992, when he declared that “The Middle East has its oil, China has rare earths”. In the years since, China has shown its willingness to use its dominance over world supply to fight political battles.

The US-China trade war sparked off when US President Donald Trump imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium imports in March 2018 has continued, and in May, Chinese state media began floating the idea of banning exports of rare-earth elements to the US. This would be a possible response to Trump’s decision to hike tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods and to blacklist telecoms company Huawei.

Previously, China had sharply limited rare-earth exports to Japan in 2010 as the two countries aregued over disputed islands. The embargo threatened the viability of Japan’s electronics industry and Tokyo eventually gave ground in the dispute. The fact that current Chinese president Xi Jinping is threatening to do the same is concerning to manufacturers that need rare earths.

“What we’ve seen from president Xi in the past couple of weeks is an implicit threat to weaponise rare earth,” says Chris Berry, president of investment company House Mountain Partners in New York. “It’s something [that], if you are in Washington or Brussels, you do want to take seriously.”

The US, whose industrial success once depended on mining, seems to have woken up to the danger.

“Last year we imported at least 50% of 48 minerals, including 100% of 18 of them,” said US senator Lisa Murkowski, a Republican from Alaska, in a statement. “That should worry everyone, particularly because it is happening at the same time that demand, for everything from graphite and lithium to cobalt and nickel, is about to skyrocket.”

For this reason, in May, Murkowski introduced the American Mineral Security Act, a bipartisan bill she said would take a comprehensive approach to rebuilding the US’ domestic mineral supply chain.

“Unless we take significant steps, we’re at risk of ceding major economic drivers to other countries. Our foreign mineral dependence is our Achilles’ heel for competitiveness, for manufacturing, and for geopolitics. And in my view, it’s way past time to address it,” she said.

Already, companies that are based in the US but mine elsewhere are exploring projects closer to home. Phoenix-based Freeport-McMoran, for instance, says it will spend $850m on a copper project in its home state of Arizona.

“Fifteen years ago, US mining was thought to be a dead industry, but now it’s a profitable area for us,” said Richard Adkerson, the company’s CEO told Reuters. At least three other copper projects are underway in the US.

Resource nationalism

Another geopolitical consideration is resource nationalism, in which countries that have large stores of raw materials try to squeeze as much revenue out of their resources as possible.

For example, late last year, Indonesia’s state-owned miner Inalum took control of the local unit of Freeport-McMoran, operator of Grasberg, the world’s second-biggest copper mine. Inalum paid $3.85 billion for a 52% stake, following several years of acrimonious negotiations with the US company.

Freeport-McMoran still gets to operate the mine, but must also provide capital funding for its now minority stake. Under the agreement, Freeport will build a copper smelter in Indonesia within five years and will invest an estimated $14 billion in the mine.

Other countries are also taking advantage of the fact that miners have little choice but to accept harsh conditions if they want access to their minerals.

At the Katanga Business Meeting (KBM) conference held in Lubumbashi, DRC, last year, Congolese officials met with mining companies to discuss legal changes that these firms argue will make mineral production in the country unviable.

Changes in the new code include a greater stake for the state in mines, increased from 5% to 10%, as well as an additional 10% share to be held by Congolese citizens. This means the mining companies must automatically give away 20% of a project for nothing.

“Change is always difficult, but in the end we can all adapt,” Simon Tuma Waku, former mining minister and architect of the new code, declared on the sidelines of the KBM. “The DRC’s mining industry will grow 18% in 2018, which is very much more than any other market.”

Mineral royalties were raised from 2% to 3.5%, while items declared ‘strategic substances’ would invite an additional 10% royalty. Among the latter are cobalt and coltan, two metals very much in demand by high-tech industries.

In Zambia, meanwhile, the government of President Edgar Lungu seized control of Konkola Copper Mines (KCM) in May. KCM is one of Africa’s biggest copper producers and was owned by Vedanta, the Indian industrial group. Lungu accused Vedanta of having breached environmental and financial regulations.

Just a week before Lungu moved on KCM, Bloomberg reports that he visited the country’s copper belt, where he signalled his intention to take over all the country’s mining assets. “I want to make it very clear that I have come here to sanction, if it’s the will of the Zambian people, that we ‘divorce’ these mines. My position is that enough is enough. The attorney general is here, the lawyers are here. They will guide us how to proceed with this divorce.”

These recent struggles illustrate just how shaky is the supply chain underpinning the planned growth of EVs worldwide. As vehicle-makers proceed with their electrification plans, they will have to get to grips with entirely new supply and logistics operations, work out how to secure sufficient supplies of the necessary materials – and come up with ways of coping with probable disruptions ahead.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet