On the point of the UK leaving the EU, British car manufacturing was revealed to be at its lowest level since 2010, falling for a third consecutive year to 1.3m units in 2019 (-14.2%), according to figures released by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) on Wednesday.

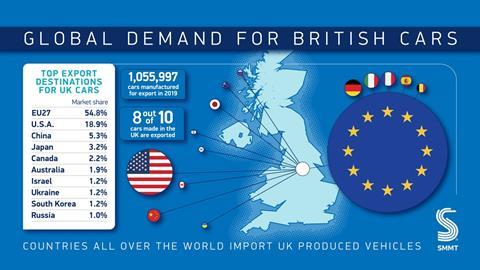

Cars produced for domestic sale dropped 12.3 % to 247,138 units while exports also took a hit, with 1,055,997 cars manufactured for export (-14.7 %). The latest production outlook from independent analyst AutoAnalysis is no more positive for 2020, with November’s prediction of total output downgraded from 1.32m units to 1.27m.

“The fall of UK car manufacturing to its lowest level in almost a decade is of grave concern,” stated SMMT CEO Mike Hawes at a press conference in London on Wednesday.

He said that output had been affected by factors including weakened consumer confidence, partly driven by Brexit; slower demand in key overseas markets, particularly China, where UK exports fell by a quarter; and a shift away from diesel vehicles across Europe.

Factory shutdowns timed to alleviate the expected disruption from the planned (but subsequently delayed) departure of the UK from the EU on March 29 and October 31 also had an impact.

Reorganising the bloc chain

With the UK leaving the EU today after the European parliament ratified Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s withdrawal agreement on Wednesday, Brexit will now enter a transition period until December 31, in which the government will negotiate its future relationship with the bloc.

“Brexit affects every industry and we were always fearful of no deal, not just withdrawal, but a no deal on the relationship [between the EU and the UK],” said Hawes. “Given the uncertainty the sector has experienced, it is essential we re-establish our global competitiveness and that starts with an ambitious free trade agreement with Europe, one that guarantees all automotive products can be bought and sold without additional tariffs or burdens.”

Despite the assumption of a trade deal with Europe by the end of the year, Hawes admitted that negotiation would be a “significant challenge”.

“The reputation of the UK has suffered, and we need to get our supply chain in order,” he said. “We work on a just-in-time basis with, 1,100 trucks coming into the UK every day. We have 12 months to prepare, or it will disrupt supply chains and manufacturing.”

Hawes continued: “Even if we can agree a no quota, no tariff, free trade agreement, there will still be checks – there won’t be frictionless trade.”

Under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, cars would be taxed at 10% when they cross the UK-EU border, a figure Hawes suggested would have serious economic implications. “If tariffs were imposed at 10%, exports and imports would be hit by £4.5 billion [$5.9 billion] per annum, a cost that would be inevitably passed on to consumers,” he warned.

If the UK and the EU agree a free trade agreement to remove tariffs for each other’s goods, UK goods heading to the EU, for example, would need to be proven as originating from the UK under rules agreed in the deal. This would prevent a country without a trade deal from accessing the EU market through the UK and vice versa.

Determining rules of origin will be a critical aspect of the negotiation, and given how closely the EU and the UK are currently integrated this will require an “unprecedented approach”, said Hawes.

He pointed out that the UK automotive industry has not had to calculate content for vehicle exports in seven years. With the average car being made up of 15,000 parts, determining the original content will be a “massive undertaking”, he said.

Despite what Hawes called the “depressing horizon” in view, he maintained that the EU-UK automotive relationship remains strong. Although shipments to the EU27 fell by 11.1%, the bloc remains the sector’s most important market, with its share of exports rising by 2% to 54.8% in 2019.

The UK’s small-volume car manufacturing sector also increased, boosting output by 16.2% last year. Meanwhile, production of alternatively fuelled cars rose by 34.7% to 192,304 units, with the SMMT saying that the UK is well-placed to lead the charge in ultra-low and zero emission vehicle development – if the right business conditions are in place.

Re-establishing a reputation

The UK’s reputation has suffered because of its political climate and trading uncertainty, but last year saw a welcome £1.10 billion of new automotive investment announced for the UK. However, Hawes pointed out that the bulk of that investment came from one of the UK’s own leading brands, JLR, which is expanding electric vehicle production in the West Midlands.

“With 2019’s investment tally some 60% lower than the £2.75 billion averaged over the previous seven years, it’s clear that more must be done to encourage overseas investors to follow suit,” he said. “We need to re-establish our global reputation.”

Hawes also stressed the importance of investing in new technologies, saying that the UK needed its own gigafactory, especially in light of Tesla’s latest project in Berlin. “If you look at what is going on in the rest of the world, we need some of that investment here, not least because of rules of origin,” he said.

“If the value of the vehicle moves from the internal combustion engine to the battery and you’re not making batteries here, it’s much harder to take advantage of any preferential trade agreements,” Hawes pointed out.

According to the SMMT, today’s connected and autonomous technology and the next generation of autonomous systems are set to give an overall annual £62 billion economic benefit to the UK by 2030.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet