Much of the focus on China’s Belt and Road programme has been on trade routes between Europe and Asia, but Chinese organisations are also investing in African infrastructure

China’s ‘New Silk Road’ initiative presents Africa with an unprecedented chance to upgrade the infrastructure and logistical capacity of its ports and other commercial facilities. Officially called the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the plan is to create a trade network that spans the globe via both land and sea routes (respectively, the ‘belt’ and the ‘road’). The project will see investment in infrastructure from Beijing to make it easier for Chinese companies to move goods around the world.

Trade between China and Africa is substantial, and exceeded $200 billion in value last year – thus making China the continent’s largest trading partner. More than 90% of the goods leaving Africa are transported by sea, meaning that ports are a vital element of the continent’s logistics network.

However, African shipping costs are high, ranging from 1.5 to 3.5 times more for the ocean transport of a container than in other regions, according to a recent report by PwC. Much of this can be blamed on poor infrastructure and inefficiency. None of Sub-Saharan Africa’s facilities are among the top 40 ports listed by Lloyds in its ‘One Hundred Ports 2018’ report, which placed South Africa’s Durban, the region’s busiest port, in 66th place.

”The average cargo dwell time in large ports in Latin America, Asia and Europe is under a week. Most ports in Africa see rather long dwell times, averaging between two to three weeks” – Gayathri Iyer, Observer Research Foundation

The BRI, it is hoped, will address many of these issues. While this initiative spans the globe, Africa arguably stands to benefit most. A newly published report by the African Development Bank (ADB) suggests that the continent’s infrastructure requirements amount to $130–170 billion per year, with a financing gap in the range of $68–$108 billion.

Although this figure takes into account roads, rail and bridges as well as ports, it is the latter that serve as the initial gateway to the continent. The ADB says that, in addition to limited capacity in terminal storage, operation and maintenance, many ports lack the capacity to handle large vessels. They are further hampered by inadequate infrastructure networks in the hinterland, such as railway lines and roads links that often lead to long delays at the ports.

Impact of the infrastructure deficit

The lack of investment is costing the continent dearly. Poor infrastructure shaves up to 2% off Africa’s average per capita growth rates, the ADB says. Only firms that have very high returns and engage in well-controlled markets can make a profit by operating in Africa, notably those involved in mining, oil production and allied activities. Companies with high value addition, broad job opportunities and wide sectoral linkages find the challenges of doing business in Africa more daunting and stay away, the ADB says.

“This is a problem common to almost all [formerly] colonised nations, as the infrastructure of colonies was purpose-built for the colonial export of raw materials to Europe, primarily,” says Gayathri Iyer, a researcher at the India-based Observer Research Foundation’s Maritime Policy Initiative. “This infrastructure deficit will therefore continue guiding most [African] countries’ trade outward rather than inward.”

Iyer points out that of Africa’s 55 countries 16 are landlocked and highly dependent on the major ports in Nigeria, Morocco and Egypt. African ports are notoriously inefficient, however, leading to long dwell times for cargo vessels waiting to unload or take on board cargo.

“The average cargo dwell time in large ports in Latin America, Asia and Europe is under a week,” says Iyer. “Most ports in Africa see rather long dwell times, averaging between two to three weeks. It then takes between four to six weeks for the cargo to reach the landlocked African countries.”

For landlocked nations that have expressed interest in developing their own automotive assembly capacity, such as Uganda and Rwanda, getting their products to market is extremely difficult.

“This has rendered many regional manufacturing companies that depend on shipments uncompetitive in global markets and led to imports being more expensive for consumers,” Iyer adds.

A key part of China’s Belt and Road

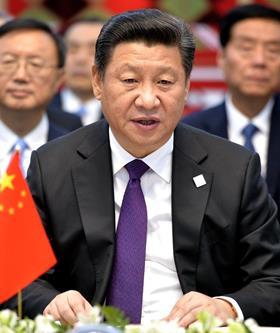

This is where China comes in. The BRI was announced in 2013, and it was clear from the outset that Africa would have an important part to play in the project. At the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation held in Beijing in June, the Chinese premier Xi Jinping said the project would continue to support infrastructure development in Africa.

In particular, Beijing’s support would come without the restrictions usually associated with loans or grants from traditional financial institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, he said.

“China’s investment in Africa comes with no political strings attached,” Jinping told the forum, claiming that “China does not interfere in Africa’s internal affairs and does not impose its own will on Africa.” The country may not impose restrictions as the global organisations do, though several nations in Africa (and further afield) have discovered that there can be another price to pay.

”If there was no Chinese infrastructural financing, we’d have a lot less infrastructure today. Long ‘development economics studies’ and ‘millennium villages’ [multisector projects] won’t bridge an infrastructure deficit” – Onye Nkuzi, Nigeria-based analyst

Altogether, China will spend at least $1 trillion on the BRI worldwide. According to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), a policy research organisation based in Washington DC, US, at least 46 African ports have been prioritised by Beijing for investment and development. The CSIS recently published a report entitled ‘Assessing the Risks of Chinese Investments in Sub-Saharan African Ports’ which takes a closer look at China’s long-term strategy for the continent’s ports.

The report notes that Beijing plans to use its African port investments to increase its military and political reach, but that most of the focus will be on extending its commercial footprint on the continent; Chinese investments will aim to address congestion and outdated port infrastructure, which currently limit trade flows on the continent.

“The 46 ports identified in our report align with Chinese military, commercial and political objectives,” Judd Devermont, one of the authors of the study, told Automotive Logistics. “One challenge is decoupling these objectives, distinguishing which ports have security dimensions from those that offer commercial gains.”

Among these ports are some of Africa’s most strategic: the Lekki deep water port in Nigeria, and the planned Bagamoyo project in Tanzania. Some analysts are concerned that as China embeds itself in Africa’s logistics infrastructure, it could potentially threaten Western interests.

Military and port management agreements could theoretically put these facilities under Beijing’s control, squeezing out Western companies which export from and import to the continent. They point to the way that China now controls Djibouti, the main port on the Horn of Africa, and its takeover of Hambantota port in Sri Lanka after the government failed to meet repayments for Chinese loans to build the facility.

“While it does not purport to reveal the next Djibouti military base or Hambantota port in Africa, the data indicates where Beijing is making a bigger bet on a port’s potential and reveals which ports are more susceptible to Chinese influence and control,” Devermont says.

For some, the unequal relationship seems worth the risk. “Warts and all, Africa is a lot better off with Chinese infrastructural financing,” says Onye Nkuzi, a political analyst based in Nigeria. “If there was no Chinese infrastructural financing, we’d have a lot less infrastructure today. Long ‘development economics studies’ and ‘millennium villages’ [multisector projects] won’t bridge an infrastructure deficit.”

An outlet for automotive

For China, the end game is surely about putting its own products in the hands of African consumers, of which there are more than a billion – huge market potential. In particular, Beijing would like another outlet for its growing automotive industry.

In fact, finding new markets for China’s cars is becoming urgent. The China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) which monitors domestic sales, reports that sales last year fell for the first time since 1992, dropping 5.8% to around 22.4m units in 2018.

“The automotive industry has been a driver of China’s economic growth for years. Now it is pulling back,” Xu Haidong, CAAM assistant secretary general, said at a briefing in Beijing, according to Reuters.

[Support for used car exports] will stimulate the vitality of the domestic automobile consumption market, promote the healthy development of China’s automobile industry, and promote the steady improvement of foreign trade – Ministry of Commerce, China

Chinese cars have failed to penetrate western markets, largely because of design and safety barriers, but these tend to be less of an issue across Africa. Meanwhile, the latter is the world’s largest importer of second-hand cars, mostly from Japan and Europe, and this sector also offers opportunities. Indeed, in May Beijing said it would begin a programme to export selected used vehicles, and would remove restrictions on their sale internationally.

The Chinese Ministry of Commerce stated that it would allow used car exports from ten Chinese cities and provinces including Beijing, Shanghai and Guangdong, and that it would offer more support to the sector. The ministry said it would identify companies that can handle such exports and help develop tests to ensure the quality and safety of second-hand vehicle exports.

“This will stimulate the vitality of the domestic automobile consumption market, promote the healthy development of China’s automobile industry, and promote the steady improvement of foreign trade,” the ministry said.

China is already making in-roads into Africa in the form of two-wheelers, with an increasing number of Chinese motorbikes seen on the continent’s roads. Retailing from around $700, these vehicles have also created opportunities for spare parts sellers and repairers of the machines. Such workshops are a common sight in Asia, and increasingly across Africa as well.

In Kenya alone, Chinese-made motorbikes now account for 50% of the 200,000 sold each year, according to the country’s National Bureau of Statistics. Such ‘ecosystems’ are likely to develop for larger vehicles too, as Chinese cars, truck and buses gain popularity in Africa.

Ultimately, China hopes to create an investment ecosystem that will see African countries locked into the Chinese economy, according to analyst Nkuzi: “The Belt and Road Initiative is about one thing – connectivity”. For instance, he explains, a company such as China Civil Engineering Construction builds the ports, roads and bridges, while electronics provider Huawei installs the communication infrastructure and finally online retailer Alibaba connects business people in China, Asia and Africa.

Aiming for free trade across Africa

China has actually been a driving force behind the establishment of an agreement to work towards a free-trade pact across the continent – bringing reluctant regional leaders to the negotiating table, arranging summits and helping to fund the process. In July, leaders of 54 countries signed the African Continental Free Trade Area (AFCFTA) which plans to create a $3.4 trillion economic bloc and boost trade within the continent itself.

Intra-African exports made up only 19% of total trade in 2018, compared with 59% for trade with Asia and 69% for trade with Europe, according to the Brookings Institution in Washington DC, US.

“On a pan-African scale, the economic impact of AFCFTA will be significant… removing tariffs on intra-African trade will boost net income at the continental level by $2.8 billion per annum,” stated Chris Devonshire-Ellis, founder of legal and operational advisory firm Dezan Shira and Associates, in a note to clients which was published in May. “China used its diplomatic, political, and trade clout to harness an agreement,” he explained.

”The Sub-Saharan Africa region’s ability to protect its automotive industry will weaken significantly as a result of the AFCFTA [free-trade deal]. This is because used vehicle importers will use the porous borders to trade” – Joshua Cobb, Fitch Solutions in Johannesburg

However, some caution that AFCFTA will complicate the emerging automotive industry across Africa. “The Sub-Saharan Africa region’s ability to protect its automotive industry will weaken significantly as a result of the AFCFTA,” says Joshua Cobb, automotive industry analyst at Fitch Solutions in Johannesburg, South Africa. “This is because used vehicle importers will use the porous borders to trade.”

In particular, countries such as Rwanda and Uganda that have plans to develop their own industry will be hard pressed to keep smuggled vehicles out. “Nascent vehicle production industries, such as that which Uganda is planning with its investment in Kiira Motors, will be very exposed to more established automotive production hubs such as South Africa, Morocco and Kenya, and are not likely to survive for long,” says Cobb.

Running into stumbling blocks

One concern raised over China’s African investments is that its largess is not guaranteed. Recently, construction of a railway line that was intended to be a flagship infrastructure project for Eastern Africa stopped, after China withheld $4.9 billion in funding needed to allow the project’s completion.

Bloomberg reports that the reason for China pulling back in this instance may lie in the project’s high profile. Chinese state media had repeatedly used the Mombasa-Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway project as a showcase for the BRI. As a result, the project had come under negative external scrutiny, with international observers noting that projects such as this were burdening poor countries with debt they could not repay.

In response, Xi said earlier this year that Beijing would more closely scrutinise the financial viability of projects and halt them if it appeared that they could not pay for themselves. Both Kenya and Uganda are now scrambling to find alternative funds to complete the railway.

Another flagship project that has run into trouble is the $10 billion, China-backed programme at Bagamoyo Port in Tanzania. The country’s president, John Magufuli, suspended planning on the development in June, after deciding that the conditions Beijing attached to the project were “exploitative and awkward”.

Bagamoyo was intended to underpin the BRI in Africa and would be the continent’s largest deep water port. Talks are underway to recommence development, but the suspension of activity may indicate a change of tack.

Eric Olander, managing editor of The China Africa Project, says Beijing has become much more reticent on offshore spending. “A lot of African policymakers have become accustomed to being able to tap vast amounts of Chinese money to fund infrastructure projects but there’s mounting evidence that Beijing is pulling back and the days of easy money may now be over,” he says.

Still, it is clear that China has a long-term vision for Africa that will result in one of the largest investments ever in the continent’s logistical capabilities. It may not deliver all it promises, but for now BRI is probably the best option for improving and developing African infrastructure.

Mena: Infrastructure, policy and regulatory developments

- 1

Currently reading

Currently readingInto Africa: China’s ambitions for a transcontinental logistics network

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet