Slightly to the north of Wolverhampton in the UK’s industrial Midlands – and perhaps more crucially just a few miles off a key transport route, the M6 motorway – lies one of the latest additions to the worldwide roster of production facilities for stamped automotive metal parts. In mid-September, Spanish-owned tier one supplier Gestamp officially opened a 50,000 sq.m production facility built at a cost of nearly £50m ($65m), after slowly ramping up over the previous 12 months. It is now one of seven production plants the company operates in the UK, plus an R&D centre, which altogether employ some 3,000 people and last year generated revenues of £557m.

Slightly to the north of Wolverhampton in the UK’s industrial Midlands – and perhaps more crucially just a few miles off a key transport route, the M6 motorway – lies one of the latest additions to the worldwide roster of production facilities for stamped automotive metal parts. In mid-September, Spanish-owned tier one supplier Gestamp officially opened a 50,000 sq.m production facility built at a cost of nearly £50m ($65m), after slowly ramping up over the previous 12 months. It is now one of seven production plants the company operates in the UK, plus an R&D centre, which altogether employ some 3,000 people and last year generated revenues of £557m.

This impressive-looking facility with its gleaming white exterior, known simply as Gestamp West Midlands, will by 2020 replace the operations that currently take place at a facility five miles away at Cannock. But, as plant director Paul Felton confirms, the new operation is far more than just a facsimile of its older counterpart. Instead, it will house several new types of production process that mark a significant advance in capabilities.

Perhaps the most notable of these is hot stamping. In this manufacturing process, boron steel is heated before being stamped and then rapidly cooled in order to generate enhanced strength. Felton confirms that the technique is already in operation at the new site using two lines, one for extra-large and one for medium-sized parts. These are supplementing two other such lines that the company operates elsewhere in the UK. The first can produce four parts ‘per blow’, a number that can be doubled by an integrated laser cutting capability, while the second line can produce two which can be doubled to four.

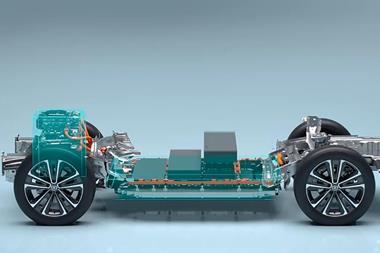

Cold stamping capabilities have also been enhanced. In this case, the upgrade is represented by a 2,500-tonne force servo press used mainly to process steel blanks, though a small number of aluminium blanks are also handled. The year after next, though, a completely new process is due to come online: the machining of aluminium extruded lengths and their subsequent assembly, without any prior stamping, into the battery housing structures for purely electric and also hybrid vehicles. As such, Felton describes the new plant as “a modern platform specifically built to showcase the technologies Gestamp now has to offer”.

Cold stamping capabilities have also been enhanced. In this case, the upgrade is represented by a 2,500-tonne force servo press used mainly to process steel blanks, though a small number of aluminium blanks are also handled. The year after next, though, a completely new process is due to come online: the machining of aluminium extruded lengths and their subsequent assembly, without any prior stamping, into the battery housing structures for purely electric and also hybrid vehicles. As such, Felton describes the new plant as “a modern platform specifically built to showcase the technologies Gestamp now has to offer”.

New production, new logisticsSupporting these new or enhanced manufacturing processes is a logistical functionality that also represents a step-change from previous capabilities. The new factory comprises a single building with only a ground level, whereas the Cannock site has eight separate structures and several different levels. Felton candidly describes the older facility, of which he is also the director, as a “logistics nightmare”.

Even before the new capabilities are exploited through enhanced materials handling, flow and storage facilities, Felton points out that there has been a fundamental change in the nature of the incoming raw materials due to the new manufacturing technologies, particularly the hot stamping processes. At Cannock, those materials are primarily in coil form with a small amount of pre-shaped blanks. At the new location, all the incoming raw materials are blanks made at another Midlands-based Gestamp company, Steel & Alloy in West Bromwich. However, Felton says that in future the use of coil is “not ruled out.”

Straightaway, that means there is no need for the heavy-duty cranes to unload incoming trucks that the sheer weight of coil material would demand. Instead, forklift trucks both unload the deliveries and carry the blanks to the stamping machines. “It is easier to unload blanks than coil,” Felton confirms.

Blanks are delivered according to a schedule set out one week in advance, with enough blanks in the plant at any one time to support “four or five” sets of stamping operations, or about 12 hours of production. These are stored in racking on the shopfloor adjacent to the stamping machines.

The controlling software for the operation is an SAP ERP system. Felton says the new plant has upgraded from an older version of the software that previously ran in the UK to the latest version, which is being adopted as a standard for Gestamp worldwide. The intention is that there will be just a single “corporate, global” version of the software for use throughout the whole company, he explains.

Making use of AGVsAfter stamping, a small proportion of the formed parts are despatched straight to customers, but the majority are transported by automated guided vehicles (AGVs) to interim storage within the plant prior to their delivery to further production areas onsite, where they will become part of larger vehicle assemblies.

The AGVs use a laser guidance system that enables them to navigate by recognising reflective markers situated along their prescribed routes; they do not use the older technique of following buried tracks in the floor. The intention is that ultimately there will be six of these machines in the plant.

Felton explains that the use of AGVs will not just save on labour costs over the longer term, but will also contribute to the automation of the pre-assembly storage of stampings as the AGVs will be able to offload the stamped parts into the storage areas. He says parts produced by the hot stamping process will go to a “dynamic, gravity-fed storage system”, while those formed by the cold process will be handled by a “very narrow-aisle, high-bay racking system”. He describes both storage systems as currently being “semi-automated”, with full automation targeted as volumes at the plant increase.

Health and safety regulations mean the use of forklifts within the assembly areas is severely curtailed, so the main method of material movement to and from them is tow trucks. The material movement within the plant from first entry to completion of all manufacturing procedures essentially consists of two operations that rely on human control and navigation encompassing one that is automated.

Felton is keen to emphasise that the new plant boasts a range of different materials handling equipment. “We’ve got reach trucks, forklifts, mobile elevated work platforms and very narrow-aisle pick-and-place systems, for instance,” he says. In addition, data gathering using manual scanning takes place to monitor and record all product movement within the plant. “We know where everything is all of the time,” states Felton.

The new facility is laid out over a single storey, unlike the older site in Cannock

The new facility is laid out over a single storey, unlike the older site in CannockServing changing OEM needsThe major output of the plant is body-in-white and chassis assemblies, all of which are built to order for customers that currently include Jaguar Land Rover, Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi, Volvo, Ford, BMW, Toyota and Honda. Felton says that, while the bulk of the output is delivered to British sites in line with Gestamp’s policy of locating its operations as close as possible to those of its customers, a proportion is delivered to one client in Austria and a small amount is sent as far as Brazil.

When asked about the possible implications of Brexit next year, he simply says: “We are working with our customers to mitigate the risk”.

Given that all product is made to order, there is no reason for assemblies to remain in the plant longer than is necessary to collate a batch for dispatch as a single truckload. As such, there is no substantial in-house storage for completed products. Instead, says Felton, the maximum time any products will remain in storage onsite after assembly is 24 hours.

Felton explains that loading onto customers’ trucks is accomplished “side-on” by forklift trucks. “We don’t have loading bays,” he says. The primary reason for this set-up, he explains, is simply customer preference, but it also benefits Gestamp by dispensing with the need for fixed structural elements for the building itself, therefore giving the flexibility to allow for future reconfiguration and expansion.

[mpu_ad]One upcoming challenge on Felton’s mind is the manufacture of battery compartments for electric vehicles, which is due to get underway in 2020. He says this will require the plant to start receiving aluminium extrusions that are six metres in length, in other words several times as long as the blanks for both cold and hot stamping operations, which range from 0.6-2.0 metres in length. “We will need new handling and storage capabilities,” Felton states.

By then, of course, the new site will have taken over completely from its predecessor. Felton says the plan is that the whole of the 800-strong workforce in Cannock will transfer to the new site; 150 have already done so. He says the benefits of the new facility for the workforce compared with the older one are already becoming apparent. “The fact that it is all on one level just makes things a lot easier,” he states. “Morale is significantly better.”

Felton adds: “No-one is shying away from the challenge of new technologies. In fact, people want to get to grips with them.”

"No-one [at the new facility] is shying away from the challenge of new technologies. In fact, people want to get to grips with them." - Paul Felton, Gestamp

"No-one [at the new facility] is shying away from the challenge of new technologies. In fact, people want to get to grips with them." - Paul Felton, Gestamp

The new Gestamp West Midlands plant increases the number of production sites the company operates worldwide to 107, with another five currently under construction. Adding a further 13 R&D centres makes for a presence in 21 countries and a total of more than 41,000 employees. Having been set up as a specialist supplier to the automotive industry in 1997, the company now has a turnover of more than €8.2 billion.

The new Gestamp West Midlands plant increases the number of production sites the company operates worldwide to 107, with another five currently under construction. Adding a further 13 R&D centres makes for a presence in 21 countries and a total of more than 41,000 employees. Having been set up as a specialist supplier to the automotive industry in 1997, the company now has a turnover of more than €8.2 billion.

According to Gestamp’s executive chairman, Francisco Riberas, that global footprint is a requirement of remaining a tier one supplier to the worldwide automotive industry in the design, development and manufacture of metal components and assemblies. “We always need to be very close to where the vehicles are assembled because that is what makes us competitive,” he states.

Riberas says the fundamental operating principle of the company takes precedence over all other considerations. As he made clear at the opening of the new West Midlands facility, that includes the UK’s impending departure from the EU. “We need to follow our customers, not wonder whether other things are happening or not,” he stated. “So we are investing in our plants in the UK.”

He argues that as long as “common sense” prevails among legislators and companies, Brexit ought to prove a surmountable hurdle. After all, “European countries are exporting to the UK,” he points out, as well as the other way around. Riberas’ view is that “Brexit and tariffs are important in the short term but they are not game-changers”.

He identifies four factors that he believes will shape the automotive industry over the near future: “connectivity, autonomous driving, the provision of mobility services and the move from combustion engines to electrification”. But of these, he thinks only the latter will impinge on the way Gestamp needs to serve its customer base. “Electrification is the most important,” he states. “The others aren’t our business.”

As such, he says Gestamp’s own R&D activities must remain focused on “reducing weight and increasing safety” while taking account of the need for new ways to do so. In the case of electric vehicles, this will involve satisfying the need for onboard battery storage – compartments which he says constitute “a completely new type of structural element”. For instance, they can be integrated with the safety cell of the car and can also alter weight distribution across the vehicle. Enabling carmakers to cope with such challenges therefore “presents an opportunity for us”, says Riberas.

As such, he says Gestamp’s own R&D activities must remain focused on “reducing weight and increasing safety” while taking account of the need for new ways to do so. In the case of electric vehicles, this will involve satisfying the need for onboard battery storage – compartments which he says constitute “a completely new type of structural element”. For instance, they can be integrated with the safety cell of the car and can also alter weight distribution across the vehicle. Enabling carmakers to cope with such challenges therefore “presents an opportunity for us”, says Riberas.

But meeting technical challenges cannot take place in isolation from that fundamental requirement to be present as a local manufacturing force wherever OEMs are making cars. “We can’t just be in a few countries. We need to be global to give us the critical mass to interact with the carmakers – otherwise, we will never be a strategic supplier for them,” he says.

"We can’t just be in a few countries. We need to be global to give us the critical mass to interact with the carmakers, otherwise we will never be a strategic supplier for them." - Francisco Riberas, Gestamp

"We can’t just be in a few countries. We need to be global to give us the critical mass to interact with the carmakers, otherwise we will never be a strategic supplier for them." - Francisco Riberas, Gestamp

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)