Vehicle-makers, tier supplies and logistics providers are progressing with ‘digital ledger’ technology that provides greater visibility and control over complex supply chains

If 2011’s Japanese earthquake and tsunami taught vehicle-makers anything, it was that they had far too little visibility in their supply chains. As production stoppages spread beyond the immediately affected plants of Toyota, Suzuki and Nissan, manufacturers as diverse as Ford, Volvo, GM, Renault, Chrysler, and PSA all found that their supply chains, too, had included factories in the disaster zone.

Toyota and Nissan were consequently among a number of OEMs to vow that, going forward, they would demand more visibility in their supply chains so that they would know not just who supplied their tier-one and tier-two components, but who supplied their tier-three, tier-four, and tier-n components.

One problem they encountered, however, was that this information is exactly the type that the customers of those tier suppliers further down the chain do not want to make known, fearing they might be sidelined, or that the information might in some way be used against them.

Something else that vehicle-makers are currently wrestling with in terms of visibility is the need to ensure an ethical and sustainable supply chain, especially given that newer types of vehicles require different raw materials.

“Blockchain technology allows for full disclosure of sustainability‑related information, without revealing competition-relevant information” – Heike Rombach, Mercedes‑Benz Cars

Cobalt and other minerals are being extracted in increasing volumes for the production of electric vehicle (EV) batteries, but at present OEMs find it difficult to see so far down the supply chain. There is a danger that, at the lower end of the supply chain, some of those materials are being obtained in a way that contravenes human rights, damages the environment and violates the OEMs’ sustainability policies.

So, how can the desired visibility be achieved, while keeping some control over the information that is shared, and without exposing suppliers to other tiers in the chain? One solution that many vehicle-makers are now investigating is blockchain ‘distributed ledger’ technology.

Blood diamonds and ethical cobalt

Blockchain offers a proven ethical-sourcing use case in the form of a global, digital registry of diamonds. Over 40 distinct characteristics have been used to produce a unique certificate-of-origin for each diamond as it travels from the diamond mine to the jeweller’s shop. This acts as a deterrent to those wanting to infiltrate diamond supply chains with so-called ‘conflict’ or ‘blood’ diamonds – those produced in war zones, often using exploited labour.

As with ‘blood diamonds’, a pressing need exists for something similar in the automotive supply chain: so-called ‘ethical cobalt’ is an issue that has come to the fore with its increasing use as EV volumes increase, and will be an ongoing concern as OEMs push forward their electrification programmes.

Approximately two‑thirds of global cobalt production is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), where small‑scale mining operations extract copper, tin, tantalum, tin, gold, and cobalt – in the process sustaining the livelihoods of approximately 2m people. Human rights violations and ‘conflict financing’ are frequently encountered, notes Nicholas Garrett, CEO of ethical sourcing audit RCS Global.

RCS Global is involved in an initiative in which Ford, cobalt miner Huayou Cobalt, software giant IBM, EV battery manufacturer LG Chem and RCS are collaborating to use blockchain technology to trace and validate ethically sourced minerals, starting with cobalt.

A proof of concept is already underway within a simulated sourcing scenario, explains Ford spokesperson Monique Brentley. Cobalt produced at Huayou’s mine in the DRC is being traced through the supply chain as it travels from mine to smelter, and then to LG Chem’s cathode plant and battery plant in South Korea, and finally to a Ford plant in the US.

Built on IBM’s blockchain platform, and powered by the Linux Foundation’s Hyperledger Fabric framework, the solution is designed to give easy access to interested parties of all sizes and roles in the supply chain.

Mercedes-Benz and supplier standards

“The transmission of contracts to each member of the supply chain is a prerequisite of cooperation for our suppliers, especially in terms of sustainability and ethical conduct,” explains Sabine Angermann, head of purchasing and supplier quality for raw materials and strategy at Mercedes‑Benz Cars. “The blockchain prototype opens up completely new ways to make purchasing processes simpler and safer.”

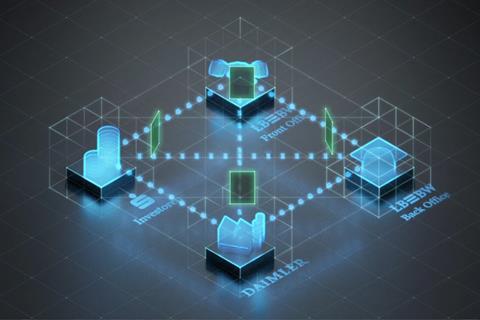

Mercedes-Benz has been using blockchain as it responds to a Daimler-wide requirement for the company’s direct suppliers to pass down the supply chain – and enforce – Daimler’s own standards and contractual requirements with regard to working conditions, human rights, environmental protection, safety and business ethics within the supply chain.

“One of the first things we ask ourselves is whether a potential use-case is a genuine blockchain use-case or not. Often what we find is that a lot of use-cases turn out to be better met by a database” – Monish Darda, Icertis

Daimler had already been using blockchain technology elsewhere, and since 2017 had been a member of Hyperledger, a Linux Foundation initiative for the development of technologies and applications based on blockchain. With such technology, Mercedes-Benz realised, it would be possible to enforce compliance with Daimler’s requirement that suppliers enforce ethical standards at their own suppliers, without it becoming apparent to third parties who exactly were those suppliers.

“Blockchain technology allows for full disclosure of sustainability‑related information, without revealing competition-relevant information,” explains Heike Rombach, procurement and supplier quality spokesperson for Mercedes‑Benz Cars. “Blockchain technology opens up completely new ways to create transparency along the value chain beyond our direct suppliers, especially when it comes to the transmission of contracts in terms of the compliance of our sustainability standards and ethical conduct.”

Conveniently, Mercedes-Benz had already been working closely with a provider of blockchain technology: Icertis, a software company that had implemented a contract management platform for the OEM.

According to Monish Darda, chief technology officer and co-founder, Icertis believed that blockchain “was going to be a game-changer” and had developed a blockchain solution in conjunction with Microsoft. Although new to the area of sourcing, he explains, Icertis could see that the Mercedes-Benz case was a legitimate application of blockchain distributed ledger technology.

“One of the first things we ask ourselves is whether a potential use case is a genuine blockchain use case or not. Often what we find is that a lot of use cases turn out to be better met by a database – but with Mercedes-Benz, that wasn’t the case,” he says.

A prototype application was soon developed and is now being evaluated. Although the Mercedes-Benz application was Icertis’ first venture into this field, says Darda, other companies have the same requirements and Icertis has now developed similar blockchain-based applications for a number of aerospace and pharmaceutical manufacturers.

BMW tests different use cases

At BMW, a dedicated blockchain team established last year is investigating a variety of opportunities. Areas under investigation include supply chain management, the tracking and verification of digital goods, Internet of Things, vehicle data management and verification, and decentralised mobility services.

For instance, one proof of concept has demonstrated how customers could use an app to keep track of their vehicle’s mileage, verify it and share it with third parties – all driven by blockchain technology.

“The hype surrounding blockchain has given way to more realistic expectations. We are convinced that blockchains represent a real opportunity” – Andre Luckow, BMW Group

“Blockchain technology holds great potential for the automotive industry,” says Andre Luckow, head of blockchain and distributed ledger technologies at BMW Group. “The hype surrounding blockchain has given way to more realistic expectations. We are convinced that blockchains represent a real opportunity and will eventually make it possible to create more decentralised platforms that will enable more efficient trading, without intermediaries, and giving consumers more control over their data. These capabilities pave the way for the establishment of new business networks and models.”

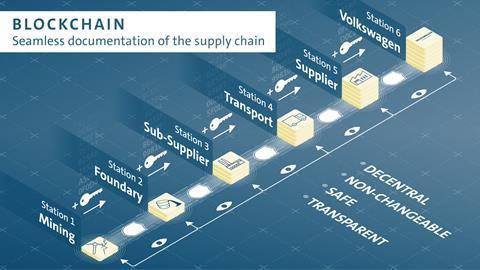

Volkswagen Group experiments

In April this year, the Volkswagen Group announced that it had entered a collaboration with blockchain specialist Minespider, which won VW’s ‘Hackathon for Supply Chain Transparency’ in 2018. The pilot project is designed to trace the supply of lead the carmaker uses in its car batteries from the point of origin (whether mine or recycling plant) to the vehicle factory. According to VW, the project will cover more than two-thirds of the group’s total lead starter battery requirements.

Minespider has built a proprietary protocol on a public blockchain composed of three layers. The first contains generally accessible information, the second contains the private data blocks which cannot subsequently be changed and the third is the encryption layer. VW said the advantage of using a public blockchain was that every company involved could work on the same system.

“Digitalisation provides important technological instruments that enable us to track the path of minerals and raw materials in cross-border supply chains in ever greater detail,” commented Marco Philippi, head of strategy group procurement, VW Group, at the time of the announcement. “Together with Minespider we will use the blockchain technology to make our processes more transparent and secure.”

The two companies are using the pilot project as the first step towards a broader collaboration and expansion of the blockchain for other raw material supply chains.

“We are witnessing a transformation of global supply chains,” said Nathan Williams, CEO of Minespider. “Companies have the right to know that their suppliers are operating responsibly and with blockchain we finally have the tools to prove it.”

Elsewhere in the VW group, Audi too has been taking a close look at blockchain technology, and last year explored the opportunities offered by a blockchain‑based supplier network. This emerged from a consideration of blockchain technology that has been taking place over several years, explains Audi procurement and IT spokesperson Elise Pham.

Meanwhile, at Seat, Raul Palacios of the OEM’s innovation and smart factory team, and its blockchain expert, confirms that the Spanish vehicle-maker has also been actively exploring blockchain, although progress to date has again been confined to proof-of-concept and prototyping projects.

“Companies have the right to know that their suppliers are operating responsibly and with blockchain we finally have the tools to prove it” – Nathan Williams, Minespider

In January this year, Seat became the first vehicle-maker to join the Alastria consortium aimed at developing blockchain-based products. The group includes 70 major businesses and institutions, including universities, banks, telecom providers and energy companies. The OEM had previously worked with Telefónica, also a member of Alastria, on the application of blockchain to improve the tracking of parts shipments to the Martorell factory in Spain.

Blockchain, Palacios notes, can optimise automotive supply chain processes and create new business models, as well as bringing trust, transparency, agility, efficiency and profitability to automotive supply chain processes. Despite all that, he adds, blockchain is not without its drawbacks.

“There are no ready-to-use productive solutions available for the automotive industry, there are many different platforms available, with no easy choice based on use case – as well as challenges such as privacy, scalability, and regulation,” Palacios states.

Blockchain and spare parts

At Daimler Trucks North America, blockchain technology from specialist blockchain provider Filament is being used within the aftermarket spare parts supply chain to track the flow of part-exchange ‘cores’ such as gearboxes and clutches as they are returned for remanufacture – one of a number of successful use-cases presently being demonstrated by the truck manufacturer, explains Filament CEO Allison Clift-Jennings, albeit the only use-case that the company has so far allowed to go public.

“The returns process at Daimler was experiencing many millions of dollars’ worth of lost parts, when truck owners traded in used ‘cores’ for new ones,” she explains. “Cores would be spread across dealers, independent service centres, aftermarket parts sellers, with Daimler having no visibility into where they really were. And then they’d wind up being sold on eBay or somewhere, when they should have been returned to Daimler.”

Challenges ahead

BMW’s Luckow agrees that while blockchain technology itself has matured significantly, challenges remain in areas such as ease‑of‑use, business ecosystems and scalability. As with computer networks and telephone networks generally, the greater the number of participants and connections, the more useful the whole network becomes.

“The main challenge is the establishment of the business networks, ecosystems and standards that are required to utilise blockchain technology to its full potential,” he says. “It is essential to create digital ecosystems that share an infrastructure and use applications with agreed standards and control models. Common, open standards and ecosystems are the only way to speed up the development and adoption of blockchain systems.”

Certainly, given blockchain’s roots as a store-of-value for anonymous holdings of so-called cryptocurrencies, regulators and tax authorities will inevitably want access to blockchain transactions for compliance and taxation purposes – if not now, when parallel paper-based systems can still be interrogated, then certainly in the future, when blockchain-based distributed ledgers form enforceable ‘smart contracts’.

Indeed, Richard Wilding, professor of supply chain strategy at Cranfield University’s Cranfield School of Management in the UK, envisages blockchain-based smart contracts ultimately replacing the mechanisms of traditional transactions, which essentially follow the way trade has been carried out for hundreds of years.

“The admissibility of blockchain contracts and distributed ledgers in courts of law, and the visibility into blockchain processes that legal and tax authorities will require, has yet to be established – thus creating friction between the old world and the new, digital world” – Richard Wilding, Cranfield School of Management

A blockchain, he points out, can be encoded so as to automatically make payments once certain conditions have been met, such as a shipment being received. Moreover, given the immutable nature of blockchain technology, those conditions cannot subsequently be rescinded or reneged upon.

“At a stroke, a blockchain-based smart contract isn’t just eradicating a lot of effort currently expended on invoice-processing and making payments, it’s also acting as an enforcer and a record of both parties’ obligations and intentions,” he notes.

“[However], the admissibility of blockchain contracts and distributed ledgers in courts of law, and the visibility into blockchain processes that legal and tax authorities will require, has yet to be established – thus creating friction between the old world and the new, digital world. The danger is that the old world wants to try to enforce its now-redundant procedures on a new world that does not really need them.”

As with many other manifestations of the global internet-enabled economy – Uber, Amazon, Airbnb, eBay and so on – the acid test for blockchain will be a simple one: does it actually deliver on its promise and bring measurable benefits?

Faurecia traces airbags

The limited evidence so far does point towards blockchain-based distributed ledgers delivering on their promise. While other manufacturers are still mostly exploring the potential of blockchain, tier-one supplier Faurecia has already concluded its investigation into the viability of the technology, using blockchain in a live proof-of-concept project with one of the company’s global vehicle-maker customers and a number of suppliers.

The project brought not only insights into how to use blockchain more effectively, but proof of a hard cash ROI, says René Deist, Faurecia’s chief information officer.

“The savings aren’t enormous, but they are worth having. You save labour, and you save time” – René Deist, Faurecia

“The pilot project was a success. What we found was that blockchain saved us time and labour. Conceptually, it acts as a shared ERP system among the various companies working together on a particular automotive programme, working especially well when changes are being made to designs and supply chain decisions – everything is recorded in the blockchain.”

The plan now is to use blockchain as a means of providing transparency and traceability for airbags; the details of every airbag that has been tested and passed will be recorded in a blockchain.

“The savings aren’t enormous, but they are worth having,” says Deist. “You save labour, and you save time.”

Applications for vehicle logistics

Equally clear about hard cash savings – and apparently close to being able to demonstrate them in practice – is Jon Kuiper, formerly CEO of terminal operator and car transporter specialist Koopman Logistics Group, and now head of Vinturas, a consortium of European logistics service providers. Vinturas is in the process of leveraging IBM’s blockchain platform to provide end-to-end visibility in the finished vehicle supply chain, from factory to dealership.

Blockchain technology, Kuiper asserts, provides a means for links in the supply chain to share data, but also remain in control of that data – and to be certain of its provenance, an important advantage in the used car supply chain, where mileage fraud is widespread.

“The Vinturas platform will allow automakers and fleet owners to manage their European flows on a near‑real time basis, improving planning, optimising inventories and networks, and saving costs,” says Kuiper. “Accessible from a transporter driver’s phone, the blockchain record is a legal document, and can be used to trigger – and pay – invoices immediately, rather than when the driver returns to base with the paperwork.”

“Lower costs, less paperwork, greater transparency, greater visibility, more predictability, greater productivity: these are all things that the finished vehicle logistics industry has been striving for – and blockchain delivers.”

Others agree. Wolfgang Lehmacher, previously head of supply chain at the World Economic Forum and now an independent consultant, sees blockchain as an e-commerce facilitation tool for the automotive industry, providing one shared real-time ‘view of the truth’ – and an immutable one. Almost inevitably, he says, the authoritative nature of blockchain records is bound to reduce cost, uncertainty and trade frictions.

“The benefits will be time savings through more efficient collaboration, and reduced procurement and customer engagement costs through automated digital processing along the automotive supply chain, while tailoring of interactions and transactions will increase customer satisfaction and loyalty.

“The revolution might come gradually, but once it’s here, the performance of automotive supply chains will be transformed – and be completely different from what we know today.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet