In past decades, international investment has flowed into the automotive industry in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) primarily due to it being a low-cost production centre. However, these days the region has much more to attract such investment, including a well-trained workforce, a wide-ranging supplier base and improving logistics infrastructure, opening up substantial opportunities for companies in all parts of the supply chain.

In past decades, international investment has flowed into the automotive industry in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) primarily due to it being a low-cost production centre. However, these days the region has much more to attract such investment, including a well-trained workforce, a wide-ranging supplier base and improving logistics infrastructure, opening up substantial opportunities for companies in all parts of the supply chain.

Production output in the key CEE markets has been growing constantly over the past few years, leaving the region with the highest rate of finished vehicles assembled per capita in the world. Slovakia tops the leader board with 183 finished vehicles manufactured a year per 1,000 citizens, while the Czech Republic ranks second with 118, according to UniCredit Bank.

The Czech Republic is one country where the industry is prospering, according to Lukas Prskavec, business development manager for automotive at the Czech Republic government agency, Czech Invest.

“For the first time, more than 1.4m passenger cars were produced in the Czech Republic in 2017. The automotive sector is the largest industry in the Czech Republic, generating more than 9% of GDP, 26% of manufacturing output and 24% of Czech exports. It directly employs more than 160,000 people, with 62% in supplier companies, as well as 400,000 indirectly,” he says.

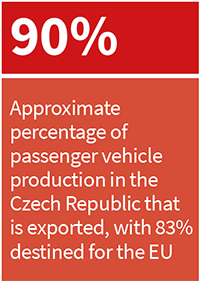

Almost 90% of passenger vehicle production there is for export, 83% of which remains in the EU, according to Prskavec. The most important partner is Germany, with a 24% share of exported cars and 44% of exported parts. As of 2017, the UK ranked second in terms of exported cars with a share of 10.5% and fourth in car parts at 4.2%.

In 2017, assembly plants in Slovakia manufactured 1.03m finished vehicles, estimates Alexander Matusek, president of the Slovak Automotive Industry Association. Most assembly plants in the region are operating near capacity, leaving production performance flat over the past six years. Production is, however, expected to grow to 1.2m finished vehicles with the launch of the new $1.6 billion Jaguar Land Rover assembly plant in Nitra.

JLR’s investment will attract more tier one suppliers who have traditionally worked with the brand, Matusek predicts – and they in turn will attract further investment at tier two and tier three levels.

Rising exports are also driving up production in Austria’s automotive industry, according to Wolfgang Komatz, cluster manager of the Business Upper Austria Institute. Austria currently produces 400,000 finished vehicles a year, and generates overall value of around €25.5 billion ($29 billion) in the automotive industry, with most finished vehicles and components being exported, according to data from government agency, Invest in Austria.

“The export rate in the automotive sector is very high, at 90%, but since Upper Austria’s companies mostly supply the German automotive industry, which accounts for 60% of exports, development in our region will depend on developments there,” Komatz comments.

Meanwhile, in 2017 Poland manufactured 514,000 passenger vehicles – slightly less than the previous year – according to estimates by local trade body, Automotive Suppliers Poland.

“Operational performance in the Polish automotive industry is tightly linked to market conditions in the EU, especially in Germany. We saw an increase in demand in the first few months of [2018], but now the upward trend is getting weaker,” says Automotive Suppliers Poland analyst, Rafal Orlovsky.

Despite this, automotive exports from Poland were expected to reach a value of at least €26.2 billion during 2018 – the highest figure ever, according to Orlovsky, with rising exports driven primarily by development of the domestic automotive components industry.

The same trends are currently playing out in Hungary, where several important investment projects have recently been launched (see AL CEE conference report ).

Overall, growing production across the CEE region has raised the importance of the Baltic Sea ports as a major transhipping destination.

Growing flows

But there is still room for further growth in the region, says Sarah Kingsbury, senior analyst, IHS Markit Automotive.

Premium OEMs entering the region include Daimler, which started producing the second generation of Mercedes A-Class at Kecskemet, Hungary, in May 2018; and Audi, which is stepping up production at Gyor, Hungary, with new SUV models. These will certainly contribute to boosting production in the region, Kingsbury emphasises.

“The region boasts a well-educated workforce, a well-established supplier base, and is a good location for delivery to neighbours in western Europe,” she says. “The CEE market is well positioned in terms of being able to move up the value chain”.

The potential from electrification and autonomous vehicles could be a further positive factor, says Kingsbury, given recent investment in Hungary, including an autonomous vehicle testing track in Zala Zone, and the creation of EV battery production sites from the likes of LG Chem in Poland and SK Innovation in Hungary.

“This takes the region in a new direction, [making it] one that is not just seen as a low-cost destination for production. That is changing anyway, with average wages increasing. Additionally, factors such as Poland’s investment status being upgraded from emerging market to developed market should also boost investor confidence,” she adds.

Vehicle electrification, in particular, seems important for the region. Groupe PSA, for example, has recently confirmed that it plans to begin electric engine assembly in the Trnava plant in Slovakia. “We have launched our electrified offensive and will have 100% of our range with an electrified offering by 2025. We will assemble electric engines in Tremery from mid-2019,” says spokesperson Clarisse Grignard.

Toyota, meanwhile, has begun manufacturing hybrid-electric transaxles at its Wałbrzych plant in Poland. This is the first time the component – which is integral to Toyota’s hybrid-electric powertrains – has been manufactured outside Asia.

Toyota spokesperson David Crouch says: “Hybrid is a key differentiator for the Toyota and Lexus brands in Europe. Going forward, we expect hybrid sales to increase even further, with a target to sell 50% hybrid vehicles in Europe by 2020. Toyota has always sought to increase local content whenever the market can support sustainable production, and that is now clearly the case for hybrid in Europe.”

Logistics providers are encouraged by such moves, too, as rising flows open up more opportunities to develop their business in the region.

“The recent OEM investments are great news for Central and Eastern Europe, providing they can find the necessary skilled staff to support these investments, as this seems a large challenge with wage escalation. The OEMs will bring tier suppliers with them too, creating more opportunities and will, of course, look to engage with local suppliers, assisting them to develop and grow their businesses,” says Stuart Stobie, group sales and marketing director of premium freight supplier Priority Freight, which in September opened a new office in Bratislava to better service the needs of customers on Slovakian soil.

“Hungary is the most productive automotive country per head in the world. It sits in the centre of the CEE region and we see it as an area in which we should have a presence to support our client base in the region efficiently and effectively,” Stobie explains.

For Imperial Logistics International, meanwhile, the focus is on Poland.

“Poland continues to be a growth market across most industry sectors. Its GDP has been growing steadily for 26 years and it is now ranked 23rd in the world. The World Bank ranks it as 24th in its Ease of Doing Business Index, and vehicles are one of its main manufacturing exports,” says Remy Hoeffler, director of the automotive business unit at the company.

Imperial Logistics has been in the Polish market for 18 years. It employs almost 1,500 people there in the automotive logistics and transport sector across four locations.

“In general, volumes [in the CEE region’s automotive industry] are growing and OEMs are planning or already building new production capacities in Eastern Europe,” says Uwe Seliger, manging director of BLG Automobile Logistics. “This has resulted in new cargo flows and we’re not always able to create paired transport. We need to constantly improve reaction times for picking up volumes from the factory, as well as transit times. It’s our job to find ways to do this and offer the best solutions to customers.”

Bottlenecks remain

There are still a few issues that companies in the automotive industry in the CEE region must be braced for, of which a workforce shortage is one of the most pressing.

“Recent production investments have certainly influenced the employment situation in Central and Eastern Europe. It is becoming harder to find qualified people and the cost of labour has increased significantly,” says Johannes Hödlmayr, general director of Hödlmayr. “In most of the countries, like the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary, there is practically zero unemployment.”

There is also an acute shortage of drivers in most CEE countries, and this is becoming a challenge, given that automotive carriers remain the main way to transport finished vehicles across the region.

“We have seen a severe shortage for quite some time already. The reasons for this situation are, on the one hand, the increasing industrialisation in CEE countries with a higher number of well-paid jobs, and, on the other hand, the very demanding [nature of the] job of a driver. Unfortunately, the drop-out ratio, especially with younger colleagues, is high. The entire industry has to stand together to make the life of the drivers easier and treat them with the respect they deserve,” Hödlmayr says.

“We are seeing a westward migration of drivers. For example, in Ukraine, thousands of truck drivers have moved to work in Poland or the Baltic states. Polish drivers, on the other hand, are moving to Germany, France or the UK,” adds Seliger. “What’s more, many drivers prefer to transport containers, for example, where they don’t need to handle the cargo themselves, rather than transporting automobiles. Here, they have to load and unload the cars by themselves, they are responsible for any damage, and they often have problems with the automobile dealer at the delivery destination.

“This is our big challenge for the immediate future. We as companies have to implement programmes to make ourselves more attractive as employers,” he explains.

In the CEE region, automotive logistics providers still have to largely rely on road transport, as the investment in infrastructure that could make alternative modes attractive in terms of price has not been forthcoming on the whole.

“We would like to use more rail transport, but the infrastructure all over Europe is very limited,” Hödlmayr comments. “Therefore, transport by truck is still the most important mode and this will not change in the next few years. Our group operates approximately 800 of its own trucks and on top of that, we also do a small share of work with fixed and ad hoc subcontractors.”

There are, however, some big projects being launched that could lead to a gradual rise in the importance of the rail sector, in particular in the Baltic States and on the EU-Ukraine and EU-Belarus borders, where different track gauges have been a constraining factor for a long time.

“Road is still the most important transport mode but, of course, the role of rail is constantly growing,” Seliger says. “Nevertheless, rail transport is not easy, going east, due to the different track gauges. That means cars have to be reloaded before entering former CIS countries, and there’s a shortage of wagons there because of a lack of investment in rolling stock over many years. For now, we’ll transport vehicles eastwards directly by truck, or by ship to ports like Bronka, near St Petersburg, for further distribution. Whatever happens, rail transport will be an important mode in the future – including in view of China’s plans for a new Silk Road.”

At the same time, motorway routes in the CEE region generally lack investment.

“We see big shortfalls in infrastructure investment. This is true for rail but also for road infrastructure,” says Hödlmayr. “The [resulting] congestion lowers productivity, as too much time is lost. We also lack sufficient safe truck parking with acceptable quality facilities for our drivers. [This is why] we are investing in our own driver accommodation at our sites.”

A further negative impact has been felt this year due to the arrival of the new Worldwide Harmonised Light Vehicle Test Procedure (WLTP), the EU’s improved vehicle testing standard which came into effect at the start of September.

“We noticed in 2018 a decline in cargo flows in the second half of the year due to implementation of WLTP standards and a bottleneck in certification of the models. A lot of units failed to arrive at terminals and were late for transport because they were waiting for certification. Now, everything has to be transported immediately and logistics providers face a lack of transport and storage capacities,” Seliger explains.

Brexit fears

The automotive industry in the CEE region is also rather worried about the terms of the UK’s exit from the EU. A large proportion of finished vehicles and parts from the region is exported to the UK, and by early January 2019 there was still no clarity on how Brexit would impact the supply chain.

Prskavec of Czech Invest confirms that most automotive sector companies in the Czech Republic are concerned about Brexit, because its exact form remains unknown.

“A development of business relations between the EU and the US is also seen with worry, although the direct impact would probably be smaller than the impact of Brexit,” he says. “In 2017, 0.4% of total Czech automotive exports ended up in the US.”

It is possible that Brexit could lead to a reduction in the flexibility, efficiency and reliability of deliveries. This would incur additional cost, conceivably right through the supply chain rather than just for finished vehicle production, according to Matusek. The eventual result would be the higher prices for customers, he adds.

The UK was the second biggest sales market for Kia’s Zilina plant in Slovakia, says Pablo Gonzalez Huerta, a spokesman for Kia Motors Europe. The plant exports 18% of its finished vehicles to Russia, 14% to the UK and 7% to Germany. Overall production in 2018 was expected to be close to 330,000 finished vehicles, slightly lower than the total in 2017.

There might be some positive factors from Brexit, however, as some UK-based manufacturers may need to relocate production operations to the CEE region, including in Slovakia, Matusek suggests.

Which transport modes are most important for finished vehicle logistics in the Baltic countries?

Short-sea shipping is by far the most important mode of transport in the Baltic States and Finland. Gefco is working closely with Baltic importers and providing short-sea and road solutions to clients.

At the national level, cars are delivered mostly by road to distribution centres or directly to dealers, leasing and rental companies, and fleets. In Latvia and Estonia, logistics companies focus on their strengths – mainly shipping ones.

What are the main challenges in the region?

Transport companies have been increasing their fleets, but most are facing a shortage of truck drivers. Such drivers need specific knowledge of how to load and secure different types of cars on different types of trailers.

Many existing drivers are approaching retirement age, being around 50-60 years old. Drivers under 30 don’t want to stay in their trucks for four or six weeks running. Truck manufacturers are now creating a database [of logistics operators and their vehicles] to help drivers and managers build loads on specific platforms for different models.

What major infrastructure projects are underway that will support finished vehicle logistics in the Baltics?The Trans-European Transport Network rail link from Tallinn (Estonia) to Warsaw (Poland) via Riga (Latvia) and Kaunas (Lithuania) has been the largest Baltic region infrastructure project in the last 100 years.

The construction of this railway – known as Rail Baltica – should start by 2020 and be completed by 2030, with the aim of integrating the Baltic states with the European rail network.

Another important project is the Via Baltica digital corridor. In the autumn, a memorandum of understanding was signed between the Baltic countries regarding the development of the Via Baltica digital corridor, with the purpose of promoting connected and automated driving and development of 5G technologies.

New 5G cross-border corridors for connected and automated mobility in the Baltics will allow for the testing of autonomous vehicles. Europe is currently the biggest experimental area for 5G technology, and has ambitions to lead in large-scale testing and early deployment of 5G infrastructure, enabling connected and automated mobility.

The Russian M9 highway – the existing road freight route known as the Baltic Highway – connects Moscow directly with Riga, where it also joins with the Via Baltica highway.

Meanwhile, significant investments in ports in Ventspils and Liepaja and in Freeport of Riga have created quays with the best international port practices, boosting the development of terminals and with that, road and rail access to port areas.

What regulatory considerations are affecting the movement of vehicles in and through the region?Overall European transport policy aims to switch medium and long-distance freight from road transport to more sustainable modes like rail, inland waterways and short-sea shipping. The most critical cross-border issue on the North Sea-Baltic Corridor is the absence of a 1,435mm standard gauge rail line from Tallinn to the Polish border through the Baltic States. This standard gauge is completely lacking across two national borders, from Estonia to Latvia and Latvia to Lithuania. A dual gauge/parallel 1,435/1,520mm track from the Polish border to Kaunas is expected to be completed soon but will still have restricted speed limits of 80kph for freight movements.

An agreement has been reached that Vilnius will be connected by a 1,435mm rail line to the Rail Baltic north/south axis at Kaunas, ensuring that all the Baltic capitals and Warsaw are connected in the same network, in line with the Shareholder Agreement of the joint venture of the three Baltic states and RB Rail AS.

Safety, meanwhile, is a significant problem on the Via Baltic road, due to the fact that it is so heavily used. It is not an official motorway and does not have to comply with the normal safe and secure parking requirements. Road safety must be encouraged to improve.

Topics

- Audi

- Austria

- Automotive Suppliers Poland

- Belarus

- BLG Automobile Logistics

- Business Upper Austria Institute

- Czech Invest

- Czech Republic

- Daimler

- Electric Vehicles

- Estonia

- Europe

- features

- Finished Vehicle Logistics

- Finland

- France

- Gefco

- Germany

- Groupe PSA

- Hödlmayr

- Hungary

- IHS Markit Automotive

- Imperial Logistics International

- Invest in Austria

- Jaguar Land Rover

- JLR

- JLR

- Kia

- Kia Motors Europe

- Latvia

- Lexus

- LG Chem

- Lithuania

- Mercedes-Benz

- Poland

- Ports and processors

- Priority Freight

- Rail

- Road

- ROW

- Russian Federation

- Shipping

- SK Innovation

- Slovak Automotive Industry Association

- Slovakia

- Stellantis

- Suppliers

- Toyota

- Toyota

- Ukraine

- United Kingdom

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)