TMUK is developing its logistics efficiency even more closely in line with the Toyota Production System and proving it can manage complex supply chain changes, writes Ian Henry

The UK is an important manufacturing hub for Toyota within its European operations, and a prime example of how carmakers have tightly integrated supply chains across the European continent (one of the reasons most, including Toyota, support the country’s continued EU membership). Following central logistics planning and strategy development from Toyota’s European headquarters in Brussels, the logistics and production control team at Toyota Manufacturing UK (TMUK) ensures the smooth flow of parts and material from sources across Britain, Europe, Turkey and beyond to the line in accordance with the principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS).

The UK is an important manufacturing hub for Toyota within its European operations, and a prime example of how carmakers have tightly integrated supply chains across the European continent (one of the reasons most, including Toyota, support the country’s continued EU membership). Following central logistics planning and strategy development from Toyota’s European headquarters in Brussels, the logistics and production control team at Toyota Manufacturing UK (TMUK) ensures the smooth flow of parts and material from sources across Britain, Europe, Turkey and beyond to the line in accordance with the principles of the Toyota Production System (TPS).

As Toyota’s output continues to increase in the UK, including an unprecedented double-model launch last year, its logistics team has been taking advantage of supply and production changes to improve costs and delivery performance for inbound logistics. It is also studying options to reduce waste and emissions over the long term – including decades from now – whether by developing new packaging standards or increasing the use of rail freight across Europe.

Toyota has two major factories in the UK: an assembly plant in Burnaston, Derbyshire in the East Midlands, which builds variants of the Auris and Avensis; and an engine plant in Deeside, North Wales, about 80 miles (130km) to the north-west, which supplies petrol and diesel engines to Burnaston and other global Toyota plants, including in Europe, South Africa, South America and Japan.

TMUK built more than 190,000 vehicles in Burnaston last year, up from around 172,000 in 2014 and 128,000 in 2011. Output of completed engines in Deeside was over 204,000 units in 2015, down from 225,000 the year before. Along with its manufacturing sites, Toyota has a crossdock operation in Burnaston that consolidates freight from suppliers.

Andy Winebloom, section manager for the production control kaizen team at TMUK, has the crucial job of making sure the inbound logistics flow to Burnaston runs in accordance with the overall logistics plan laid down by the central European logistics organisation. As in Toyota’s other European markets, central planning is followed by decentralised execution, with different 3PLs serving each plant. TMUK outsources logistics for Burnaston to Transfreight, for example. There are similar arrangements for other Toyota plants in Europe, with companies like Gefco, Yusen and Toyota Tusho playing similar roles to Transfreight.

The need for efficient inbound logistics was especially important when Burnaston switched to new versions of both the Auris and the Avensis at the same time in 2015. In fact, a double change like this had never been attempted at any Toyota plant outside Japan. The scale of the shift was such that it entailed 2,500 parts changes and 155 different variants. This led to great complexity for logistics; for example, TMUK had to fit a BMW engine into a Toyota engine bay with all the attendant fixing modifications. According to Burnaston’s deputy managing director, Tony Walker, this was achieved without any disruption along the supply chain.

Multimodal supply routesToyota’s inbound supply chain to Burnaston is a mix of strong local supply in the UK, combined with an important flow of European and global parts. According to Winebloom, about 80% of the factory’s needs, as measured by volume, come from UK supply points, including engines from Deeside. The other 20% is from areas including Turkey, the EU and Japan.

In the UK, inbound material moves entirely by road to Burnaston, without any rail freight. This is partly because the plant and surrounding area lack a railhead, though Winebloom says Toyota would consider using a nearby centre that has been proposed as a future rail freight hub.

Transfreight collects material from suppliers based on the central logistics plan, following a high frequency, low-inventory principle. Depending on the supplier’s volume, this usually means several collections per day. Some parts, notably seats, door trims, wheel-tyre assemblies and some metal assemblies, are built close to the plant and delivered to Burnaston on a sequenced basis, often dozens of times per day. Toyota also sequences parts itself inside the factory, such as glazing and panoramic roofs.

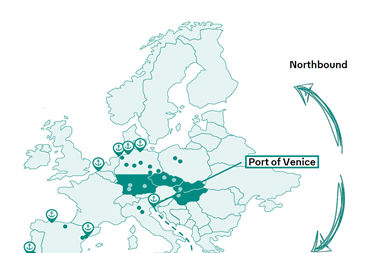

Other parts arrive from other Toyota plants and suppliers on the European continent, including engine and powertrain parts, as well as lighter material. These are typically grouped together at one of five Toyota-owned crossdocks, or six consolidation centres, before being moved onward to the UK by truck through the Channel Tunnel rail link. The crossdocks are in France, the Czech Republic, Poland, Turkey and, since last year, Poland (as well as the crossdock in Burnaston). Consolidation centres, which are run by independent providers and typically multi-user, multi-industry facilities, are in Portugal, Spain, Germany and Italy, with two in France.

Material also comes from further away. TMUK imports components from Turkey that are common between the UK-made Auris and the Turkish-made Corolla and Verso – mostly non-visible, metal chassis parts. These are sent to the UK by ship, although they move to other European plants via rail from Turkey to Hungary.

Japan is another important supply source. As Toyota builds a hybrid version of the Auris in Burnaston, it imports hybrid system components from Japan, including HV batteries, inverters and transaxles. Around 30 containers per week arrive on one of three weekly vessels at either Felixstowe or Southampton, depending on the shipping line used. From the port, Pentalver Transport moves the containers by road to its distribution point at Cannock, around 30 miles from the plant.

TPS principlesAndy Winebloom emphasises that Toyota is increasingly applying the principles of TPS to its logistics operation, an important change from even a few years ago, when the company’s aim was to cut costs. TMUK’s corporate planning section manager, Rob Gorton, explains that the focus solely on costs did not adequately take into account the company’s aims to take a more holistic view of the supply chain. Notably, Toyota runs its logistics according to the core TPS principle of heijunka, which translates as smooth or even flows, without fluctuations in volume or time.

This means that Toyota wants an efficient, smooth delivery system and for suppliers to experience the same in their own production and supply chain. Uneven or bunched deliveries are inefficient, because they inevitably mean more storage of finished parts at the supplier or at the recipient Toyota factory. In practical terms, Winebloom explains that this approach results in multiple deliveries and collections per day from suppliers. For example, some sequenced suppliers deliver 20-30 times per day, while non-sequence suppliers average around four per day. Such arrangements are seen as much more efficient than less frequent delivery, such as larger collections every other day.

“Looking at logistics through the mindset of the Toyota Production System will result in the lowest overall cost,” says Winebloom. Such frequency, consistency and truckload planning, together with flexibility, underpin the logistics at TMUK, he adds. The plant’s logistics are based around a 66-second ‘takt’ time on the assembly line – the amount of time each task takes to be completed.

Rail aspirationsThis focus on speed and cyclical timing is part of the reason TMUK, like other global Toyota networks, relies on a high usage of truck transport for its inbound logistics compared to rail flows, which are based on higher volumes and less flexible schedules – and which have suffered a few false starts.

For example, Toyota had tried using rail wagons for transporting engines and transmissions from Poland (as opposed to sending truck trailers on the Channel rail link). These came through the Channel Tunnel and arrived at Barking, in east London, which has a rail spur connected through the tunnel on a European gauge. However, from Barking the material needed to be unloaded onto trucks for delivery to Burnaston, since the height and gauge of European freight wagons are incompatible with the rest of the UK rail network. Toyota eventually decided that the unloading and reloading was too time-consuming, disruptive and costly.

Furthermore, using rail wagons directly from Europe has at times been unreliable and inflexible. For example, if freight is delayed prior to reaching a consolidation point or specific marshalling yard en route, a spot on the train could be lost and result in delays of 24 hours (which can be the case as many large freight trains travel only at night on certain sections of a route). Such delays can inevitably result in problems with just-in-time and sequenced deliveries, or require more safety stock at the plant.

"With every model change we look for opportunities to develop the packaging further to meet the needs of all the stakeholders – production, internal and external logistics, and the supplier." - Andy Winebloom, TMUK

"With every model change we look for opportunities to develop the packaging further to meet the needs of all the stakeholders – production, internal and external logistics, and the supplier." - Andy Winebloom, TMUK

Despite these problems, Winebloom says the carmaker is keen to increase its use of intermodal transport, eyeing efficiency and cost benefits, as well as environmental gains in carbon and traffic reduction. Long term, the EU has already set ambitious carbon reduction plans, including a white paper that calls for the majority of freight transported more than 300km to move by rail by 2050.

Over the coming decades there are plans to increase the European-linked rail network in the UK beyond London, which would make the transport more effective. Even closer to home for Toyota, there is a proposal to build a large, public-use rail freight interchange, dubbed the East Midlands Gateway, near to Castle Donnington. This facility would be fewer than 20 miles from Burnaston by road, and could receive rail shipments directly from a European departure point. The mode would be particularly viable for heavy items, such as powertrain parts from Poland, says Winebloom. Construction of this option, however, appears to be a long way off.

Although its experience with rail has not yet been adequate, Toyota is working to overcome these problems in the shorter term as well, including in project groups with the UK trade body, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT), and individual car companies. Some proposals include the possibility of organising dedicated trains to bring in automotive components from Europe for UK manufacturers as a group, although such an approach would require different carmakers in the UK to coordinate inbound delivery arrangements. Currently, there is a long way to go before such an idea might become reality.

Although using rail for transport into the UK has been problematic, Burnaston receives parts that depend on rail elsewhere on the European continent. For example, Toyota moves parts by rail from northern Spain to near its Valenciennes assembly plant in northern France. Parts for the UK are sorted at the neighbouring Petite-Forêt crossdock facility, merging them with parts from elsewhere in Europe for use at both the Valenciennes plant and at Burnaston. At Petite-Forêt, parts for the UK are loaded onto trucks for onward shipment on the Channel Tunnel link.

Packing for the futureAlong with improving logistics, Winebloom and his team are also focused on packaging goals, such as standardising pallet sizes, and improving returnable packaging. New model changes in particular bring opportunities to re-engineer packaging, including adapting it to suit new parts shapes and new production process requirements, says Winebloom. “With every model change we look for opportunities to develop the packaging further to meet the needs of all the stakeholders – production, internal and external logistics, and the supplier – we look at better ways of using the pallets we have” he says.

Another complex issue is what to do with empty packaging. Among UK suppliers, Toyota has found it is most efficient to use reusable boxes and return them empty to the supplier in a closed-loop transport system. The trucks that serve these closed-loop routes are dedicated to and only used by Toyota. Parts and material arriving from continental Europe or on container ships from Japan, however, are shipped in disposable packaging.

Further challenges will emerge as the factory prepares for the introduction of further new models based on Toyota’s new global architecture

Further challenges will emerge as the factory prepares for the introduction of further new models based on Toyota’s new global architectureTMUK’s approach to logistics encapsulates the carmaker’s philosophy especially well and with the recent changes to the new Auris and Avensis, it has shown it can implement new processes through its plant and supply chain, from sourcing through to logistics and manufacturing in parallel. Similar challenges will emerge in future as the factory prepares for the introduction of further new models based on Toyota’s new global architecture, or TNGA, which will put even more emphasis on standardising parts, with consequences for logistics and packaging. The Deeside engine plant, meanwhile, was earlier this year chosen to manufacture hybrid engines for a future Toyota crossover model, which will be built in Turkey.

Meanwhile, though the UK may remain embroiled in debate over the upcoming referendum on it EU membership at the end of June, TMUK remains closely connected across its European and global supply chain (part of why its deputy manager director Tony Walker has endorsed an ‘in’ vote on behalf of the company). As such, regardless of the vote’s outcome, the company’s aims of improving efficiency, increasing rail flows and reducing emissions on a European basis will be maintained.