The merger attempt by FCA and PSA will be complicated but makes economic and operational sense, including for supply chain management and logistics. Whether or not it goes ahead, more consolidation is likely as the automotive industry gears up for electrification

The pace at which PSA Group and Fiat Chrysler Automobiles appear to have agreed a deal to merge and create the world’s fourth largest carmaker is remarkable, with an agreement in principal hammered out in just a few days.

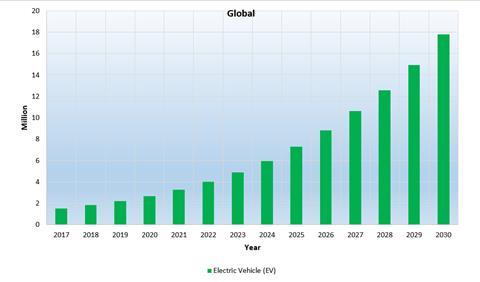

Although hurdles remain before a final merger, that speed suggests a growing urgency across the automotive industry. In the face of mounting pressure to invest in new technology, notably electrified powertrains, expensive fines over emissions, and the risk of a prolonged slowdown in global vehicle sales, traditional automotive players need to gain even more economies of scale and pool risk to make these transitions – if not to survive (download our latest foreast and analysis of global powertrain shifts below).

A speedy merger deal was something of a sprint following a long, uphill marathon that anticipated how tough things could get for the automotive industry. Back in 2015, FCA’s then CEO, the late Sergio Marchionne, made his ‘Confessions of a capital junkie’ plea, warning manufacturers against independently developing expensive technology, such as powertrains, that would eventually be commoditised. Since then, the carmaker has sought merger partners, with overtures, rumours (and rejections) with the likes of General Motors, Hyundai, Volkswagen Group and Chinese OEMs.

Earlier this year, a merger between FCA and Renault proved too complicated and was abandoned.

PSA, meanwhile, bought Opel/Vauxhall from GM two years ago and its chief executive, Carlos Tavares, has courted more candidates for acquisition. Earlier this year he said that PSA could buy Jaguar Land Rover from Tata (Tata said it will not sell). Tavares has also been frank about the costs and challenges of tough EU emission targets, as well as his plan to bring PSA back to the North American market.

A combined PSA-FCA does not solve all of the problems across both companies, including weaknesses in China and Asia, or their current lack of advanced electric powertrain technology. And navigating interests between French, Italian and American shareholders and governments – especially in the current mood of economic nationalism – will not be plain sailing.

But the merger certainly makes sense, bringing together two brands with strong profits in North America and Europe, and providing more opportunity to share platforms, mitigate fines and pool investment in electrification. With expectations for sharp growth in a variety of electrified powertrains over the next decade, few companies will be able to go it alone. We think it a sign of much more to come.

Profits today, gone tomorrow?

We forecast a tough period over the next few years for the automotive industry (read our global forecast and outlook here). A softening economic climate, trade tensions and political instability have contributed to declines in global vehicles sales over the past two years. Most OEMs have issued profit warnings as demand has weakened in virtually every major region and emerging market. At the same time, investment is ramping up for electrification, autonomous driving, connectivity and shared mobility models.

And yet, sales might not recover in the short term. We don’t anticipate any significant momentum until well into the next decade. Profits are at risk.

At 4-8%, carmakers and tier suppliers have lower average operating profits than most other industries. This has in part been because of high capital investment requirements, along with highly competitive and often fragmented markets. A low return on capital employed also makes it difficult to justify the technology and manufacturing tooling required for an electric future, especially as electric vehicles are much less profitable for most OEMs than vehicles with standard internal combustion engines.

PSA and FCA both exemplify many of the current challenges. In 2018, FCA achieved revenues of €110.4 billion ($123.3 billion) with operating income of €4 billion, an operating margin of just 3.7%. It has recently performed better, with third quarter profits in North America surpassing 10%. Its European results, however, remain in the red, whilst the company has struggled in most other global regions. With the economic outlook in the US weakening, it is understandable why FCA is keen to seek alliances.

PSA reported revenues of €74 billion last year with operating income of €4.4 billion for a margin of 5.9%, including a slim profit for Opel/Vauxhall for the first time in 20 years. This year, PSA has defied industry averages with operating margins of 8.7%, supported in part by Tavares’s successful cost efficiency, a fast transition to new, consolidated platforms and improvements in reducing vehicle inventories. However, further cost efficiency savings are thought to be minimal, and PSA’s primary markets in Europe are in decline.

Size has long mattered for the automotive industry to gain economies of scale in purchasing, engineering and manufacturing. But rarely have so many factors aligned at once to challenge the sector’s major players, and with it the requirement to share in investment and risk.

Reasons to say ‘I do’

Combining the groups would result in volumes of around 8.5m vehicles per year and with annual revenues of €184 billion and profits of €8.4 billion (4.5% operating margins). Together, the companies would have a number of advantages.

Premier league player The merger would effectively create the fourth largest global automotive group, behind the Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance, Toyota and VW Group. The new entity woul consist of a diverse range of brands and model types across Chrysler, Ram, Fiat, Alfa Romeo, Jeep, Dodge, Maserati, Peugeot, Citroën, Opel, Vauxhall and DS.

Platform sharing FCA and PSA already collaborate on commercial vans, however the merger would allow more costs savings. PSA has quickly applied platform sharing with the 2017 acquisition of Opel/Vauxhall and this has helped restore the ailing OEM to profitability. FCA’s SUV platforms could help PSA with its expanding lineup, while PSA has two platforms that it will use to electrify its range, the eCMP and the EMP2. Both companies’ premium brands – DS, Alfa and Maserati – have struggled, but combining their technology and engineering could be an advantage.

Economies of scale With both brands behind other major OEMs in the race to electrification, combining forces could help accelerate investment and mitigate risks. The companies have suggested they would find synergies of €3.7 billion, assuming no plant closures. The larger combined group’s purchasing capability would allow savings realised by more efficient resource allocation for investments in platforms, powertrains, advanced technologies as well as in the supply chain and production. It could prove vital in manufacturing and selling EVs at a profit.

Plant capacity utilisation Overcapacity has been a particular problem for OEMs in Europe, including PSA and FCA. Fiat’s Italian factories had a capacity utilisation rate of just 57% in 2018 which is highly cost inefficient. Strong unions in Europe will resist job cuts in Italy or France, and the French government’s 12.2% share in PSA could also make this more complicated.

Regional synergies Peugeot does not have a North American presence (besides a small mobility service that uses other vehicle brands), so it could leverage FCA’s penetration with established brands like Chrysler, Jeep and Ram in North America and Latin America. Whether it would accelerate plans to enter the US with local platforms remains to be seen; it could well avoid further market fragmentation and use profits from North America and Europe from existing brands to support wider expansion.

CO2 Targets FCA is considered the least advanced of the major OEMs in terms of electrification. So much so that FCA has chosen to pay Tesla €1.8 billion to pool emissions to meet EU targets for 2020 and 2021 rather than pay even bigger fines. It has also recently suggested that it could buy EV platforms and powertrains directly from Tesla. Further ahead, FCA needs to bring down its fleet average emissions to meet ever-tightening targets. Merging with PSA, which is more advanced in low emission technology, would help the combined group achieve overall targets.

Autonomy The trend towards autonomous vehicles also requires large investments. A larger group would help the brands to compete more effectively with the major OEMs and tech giants on a global stage.

Don’t rush to the alter

This Italian-French-American marriage could, however, lead to many family bustups. Along with government and regulatory authorities, the new group will have to deal with a complex shareholder structure. And in some areas, combining two sets of weaknesses does not equal a strength.

Heavily reliant on the Europe and US Both PSA and FCA need to improve their global sales reach. FCA is too reliant on North America and PSA on Europe. The combined group helps balance the global sales penetration somewhat, but does not help in China, for example, where both companies have struggled.

EV challenge The combined company would still have relatively little experience in electric vehicles. PSA has a broader plan to expand its electric powertrain offering and production network, but is well behind rivals such as Renault Nissan and Volkswagen Group. FCA’s recent investment in a battery assembly complex in Italy is just a small step. Even in a combined group, further partnerships may still be required in electrification.

Factory threats The companies said there are no plans to shut factories, and their relative balance between North America and Europe would lead to relatively little immediate consolidation. But unions are concerned about the impact upon Vauxhall’s UK plants, especially given Brexit uncertainties. It is feared that the Italian government will be keen to retain Fiat’s factories, and likewise the French government’s part-ownership of PSA will protect French plants. Ellesmere Port could well be the sacrificial lamb.

Not a done deal The share ownership structure of the two groups is complicated and heavily politicised. PSA is part owned by a Chinese state-owned company, Dongfeng (which could be an issue with American authorities). The French Government owns part of PSA. There is also the Agnelli family which partly owns FCA. A new structure based in the Netherlands has already been agreed, but the balance of powers will be difficult to maintain.

Regulatory Approval Any agreement will also have to pass muster with competition and mergers authorities not only in Paris or Rome, but Brussels and Washington DC.

Four weddings and a funeral Mergers are no more guaranteed to last than marriages, or to be sustainable on their own. Chrysler is part of a long history of acquisitions and mergers, most notably the failed DaimlerChrysler. Successfully integrating two complex international businesses is hugely difficult. Plus, formal mergers are difficult to get out of and lack the flexibility offered by other forms of partnerships, such as the simpler technology sharing agreement seen by Ford and Volkswagen.

M&A Motors

Despite the challenges of a merger, we believe that the climate of technology change, slowing sales and uncertainty will lead to more formal and informal consolidation in the automotive sector. OEMs are likely to make similar strategic moves. Even those as large as Ford and General Motors lack the scale to compete in the race to electrification. By 2030, we expect that the current 20 major OEMs could be reduced to 10-15 key groups.

Over the next decade, we also expect more joint ventures, technology exchanges, platform sharing, alliances and partnerships to increase cooperation in the industry. That could also include OEMs purchasing minority stakes in other companies, as is becoming prevalent. Toyota recently increased its stake in Subaru. There have also been reports that VW could purchase a stake in Tesla, although the companies have denied it.

A similar transition is also occurring amongst tier suppliers seeking vital economies of scale. Recently, Honda Motor Company and Hitachi Automotive Systems agreed to merge four of their car components businesses including Keihin Corp, Showa Corp. and Nissin Kogyo Co. to create a supplier with sales of around $16.5 billion. In some cases, OEMs are also bringing the supply of some key components back inhouse, at least partially. Tesla is developing battery Gigafactories with Panasonic, for example, and VW has a similar venture with Northolt for batteries.

Ultimately, the FCA-PSA merger would place the companies in a much stronger place than would no merger. The pooling of resources, cost savings, purchasing power and economies of scale would give the combined group the best chance to compete in the race to electrification and other next generation technologies.

The interesting part will be to see whether this new Transatlantic tie-up triggers a new wave of automotive M&A activity and industry consolidation.

Automotive Intelligence

This analysis is from the business intelligence unit of Automotive from Ultima Media, which also publishes Automotive Logistics. Download our latest powertrain forecast below, and keep up with analysis on other industry trends here.

For more information contact:

Daniel Harrison, automotive analyst

Christopher Ludwig, editor-in-chief

Downloads

Automotive Powertrain Forecast 2020-2030_Automotive Logistics

PDF, Size 2.95 mb

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet