Container pool shrinkage is an issue that has a costly impact on OEMs and tier suppliers across the automotive industry. At various points in the extended supply chains which support today’s vehicle manufacturing operations, containers go missing, are misused or are even stolen to be resold and used elsewhere

Container pool shrinkage is an issue that has a costly impact on OEMs and tier suppliers across the automotive industry. At various points in the extended supply chains which support today’s vehicle manufacturing operations, containers go missing, are misused or are even stolen to be resold and used elsewhere – in the industry or outside it. Lack of visibility over the movements of containers makes it hard to put a number on the scale of the problem, but one carmaker attending an ideas lab at the Automotive Logistics Global conference in Detroit last year said it would be easy for an OEM to lose 10% of its pool.

Given that one vehicle-maker and its suppliers may have hundreds of thousands of containers in circulation, the combined total loss for the industry is sure to be vast, with significant implications for costs, efficiency and sustainability.

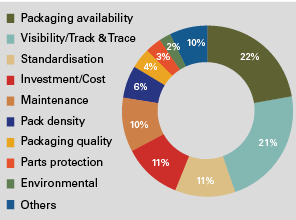

For this reason, OEMs have started to pay more attention to visibility in their packaging operations. A recent Automotive Logistics survey of senior automotive industry executives revealed that visibility comes a close second in their list of top priorities, just below the actual availability of packaging (see graph below).

As part of this move towards improving the oversight of their container fleets, various OEMs are now investigating different types of tracking technology to provide more visibility. Nissan North America (NNA) is one of them.

In spring last year, the OEM started exploring the merits of GPS (global positioning system) technology to provide better visibility of the containers of parts moving through its supply chain.

“The idea came about because we were struggling to determine the root cause of container shrinkage that we were experiencing between the plant and a few of our key suppliers,” explains Anthony Brownlow, packaging engineering manager at NNA with responsibilities across its operations in Tennessee, including the Smyrna vehicle assembly plant, the Decherd engine factory and the OEM’s export centre.

The problem – similar to that experienced by other vehicle-makers – was that suppliers were contacting Nissan to report that they were short of containers and to ask if these were to be found anywhere on the OEM’s property. From Nissan’s point of view, the containers had been loaded onto a truck at its return centre, but beyond that it was unable to say what had happened to them between its own facility and the supplier’s premises. The suppliers, meanwhile, believed that the containers had not been returned.

The only way to try to track down the containers and establish who had last been in control of them was to go through paperwork, such as bills of lading and manifests, a slow and tedious process. “We realised that our visibility outside of our campus was limited,” states Brownlow.

He and his packaging team started brainstorming ideas for how to address this lack of visibility, taking inspiration from technology already being used in the transportation industry and, indeed, by ordinary users of mobile phones for navigation.

“The question was: could we use that same technology – GPS tracking – to solve packaging issues?” Brownlow explains.

About Anthony Brownlow

Manager of packaging engineering at NNA for the past year, Anthony Brownlow leads the team which is responsible for new model packaging development, plus the coordination and buy-off of Nissan and supplier-based packaging to support incoming models.

He works at the vehicle assembly plant in Smyrna, Tennessee but has oversight of packaging operations across Nissan’s other locations in North America: the Decherd engine plant, also in Tennessee, plus the export centre. He also collaborates with Nissan’s partner, Daimler, to provide packaging services for engines produced by both companies.

Before his current role, he spent three years as manager of logistics strategy at Smyrna and leading start-up activities for its 1.5m sq.ft (140,000 sq.m) Integrated Logistics Center which opened in 2016 at a cost of $160m.

Brownlow was responsible for transition plans relating to warehouse consolidation, trailer flow movement, part sourcing impact and capacity tracking.

His other management roles at Nissan have included manager, iFA material flow strategy, and manager, bodyshop material handling.

Tracking down the right tech

There are a number of technologies available that can be used for tracking, including RFID (radio frequency identification), BLE (Bluetooth Low Energy) and of course GPS, but Nissan needed to find one that could cope with monitoring the exact location of containers in the context of its cross-border, international supply chain.

“The more miles and touchpoints in the supply chain for containers, trailers or any asset [and] the more providers you count on, the greater the risk to the supply chain for various types of disruptions, a few of those being compliance, delays and misroutes of varying degrees,” says Brownlow, giving some idea of the scale of the task.

Nissan settled on GPS because its key benefit is that it can locate an asset at all times, whereas an RFID tag that can be read at the gates of a facility – a cheaper technology – merely acknowledges the arrival of the container it is attached to; if the container fails to arrive in the first place, the RFID cannot say what happened between one gate and the next.

”If you put the GPS on a container not only are you tracking a lost container, you’re getting to view carriers, trailer assets, drop yards [and] crossdocks” – Anthony Brownlow, Nissan North America

Other key questions to address in the search for the right equipment included the length of battery life in the tracking devices, their fitment to the containers, location accuracy and ability to pull and aggregate data. Through trial and error, says Brownlow, Nissan found a GPS system, from Surgere, that suited its requirements: trackers that could be fitted to a bulk container or steel rack, supported by software to handle the incoming data.

The GPS tracking units can be fitted to the bottom of containers, such as 30 by 32 or 45 by 48 bulk bins, inside the celled structure of the bases. The units cost $400 each, then $500 on top of that for a year of service, therefore amounting to an outlay of nearly $1,000 per container in the first 12 months; visibility, it seems, comes at a price.

Nissan kicked off its project in April 2018 with five tracking units, but over the course of a year broadened this out to 45 across 30-40 suppliers. The GPS may have involved a cost premium, but it soon became clear that the initial outlay would be more than compensated for by what the technology enabled Nissan to discover.

On the trail of violations

Container misuse is commonly found across the automotive industry and can include tier one suppliers using them to service their own relationships with suppliers further down the chain, inter-company part transfers stretching the container route without permission, and even theft. With the help of the GPS, Nissan confirmed that its own situation was no different.

Out of the sample of the suppliers with tracked containers (a relatively small proportion of the nearly 500 that Nissan uses in North America), the contract violation rate signalling some form of misuse was around 30-40%. The theft rate was about 5%.

The usual OEM-supplier packaging contract drawn up at launch takes into account all relevant factors such as distance, stop points and the total loop in order to calculate the number of containers needed to support the operation, which means that a container going outside that circuit is a contract violation and also results in the container fleet going short. This happens in the case of tier one suppliers using containers to service their tier two relationships; containers are sent from the OEM to the designated supplier facility, but then passed on to a tier two location.

When it comes to the stretching of fleet routes – and other cases of misuse, and indeed theft – the US-Mexico border is a particular hotspot. Many automotive components are produced in Mexico and transported to vehicle assembly plants in the US, but if a US supplier sends containers over the border from its warehouse, to be loaded with parts at a Mexican manufacturing facility, that could violate the initial contract if it did not inform the OEM of its intent to do so; otherwise, as far as the OEM is concerned, the point of origin would be the US warehouse, not the Mexican plant.

Cases of theft

Lack of discipline is one thing, but theft is quite another. In one case, Nissan discovered that a container had been transported to a reseller, its labels and logos had been removed and it had been sold to a major tier one supplier. Furthermore, the warehouse that sold it was then found also to be storing containers from other OEMs, prompting Nissan to contact them to share the news.

However, it is important to point out that suppliers are not necessarily aware of everything that is happening with the containers – just as Nissan had not been fully aware until it trialled the GPS. What the new-found visibility has done is, firstly, curtail circular arguments about who last touched certain containers, thus saving a lot of time, effort and money. Less commonly, it has flagged up examples of criminal undertakings by rogue individuals. According to Nissan, most suppliers have been very receptive to the GPS technology and indeed have made inquiries about best practice.

“We were struggling to determine the root cause of container shrinkage that we were experiencing between the plant and a few of our key suppliers” – Anthony Brownlow, Nissan North America

Since the GPS project began, says Brownlow, Nissan has “closed out a significant number of those [packaging issues] through addressing broken processes, misroutes, excessive holding of containers and in some cases theft”.

This was mostly a reactive stance to address the common scenario of suppliers complaining to Nissan of container shrinkage, but now the OEM is keen to proactively tackle the worst cases of violations and theft, especially along the US-Mexico border. The OEM has created a “heatmap” of high-risk suppliers, based on characteristics such as location, type of services (milkrun being riskier than direct transport) and history of claims, so that it can analyse, investigate and if necessary take action.

Becoming proactive

Brownlow is confident that, in addition to the problems it has already tackled, the GPS tracking project has changed Nissan’s attitude towards the packaging issues it has been facing – and has also stirred up further possibilities for greater visibility and efficiency.

“When it first started off, we were in what you could call ‘reactive mode’, we were learning what is the best way to handle these types of situations between us and the suppliers. So now we have dialled in our process, we have figured out the best way to use this technology. We have moved from a reactive to a proactive approach,” he states.

“What we learned was, if you put the GPS on a container not only are you tracking a lost container you’re getting to view carriers, trailer assets, drop yards, crossdocks – you’re getting to see it all.”

One of the gains from the project is therefore a more accurate picture of the container fleet size needed in Nissan’s inbound supply chain – something that can also be applied to the trailer fleet for its outbound operation.

“For example, [for] a part sourced to an international or cross-border supplier, a container fleet is going to see trailer drop yards and crossdocks before getting to the supplier. So we plan on using GPS to aggregate data to determine what the fleet size needs to be – with a precision that we haven’t had in the past,” says Brownlow.

On the outbound side, Nissan is now investigating truck lane efficiency, given its new ability to cross reference carrier data with its own. This enables the OEM to ask, and answer, a number of important questions, according to Brownlow: “What does [the data] tell us we need for a trailer fleet? How efficient is this specific carrier? Then for current carriers, what can we do to help with bottlenecks that will benefit both of us?”

Besides tackling container fleet size issues, Nissan is applying the technology in several other ways. For onsite shuttling operations it is now replacing stopwatch data with GPS data to determine cycle times. “If we have a volume change or a warehouse re-balance, we can plan for it and then we can use GPS to validate it. [This helps us to improve] the accuracy of our planning and make faster adjustments,” Brownlow explains.

“Now we have dialled in our process, we have figured out the best way to use this technology. We have moved from a reactive to a proactive approach” – Anthony Brownlow, Nissan North America

“We’re hearing from different suppliers with regard to their concerns and taking into consideration route complexity to build our strategy for deployment,” Brownlow states.

The GPS project is ongoing, but will remain targeted rather than rolled out universally across Nissan’s North American supply chain. Brownlow says a “tactical approach” is necessary because the cost of the technology, the size of the container fleets and the battery life of the trackers mean it is not really scaleable.

But, he says, Nissan’s North American facilities are working “cross-functionally” to implement best practices and he emphasises that he is in contact with colleagues at the other sites on a daily basis to discuss the latest findings.

Bigger picture

In addition to providing greater visibility on Nissan’s own supply chain, using GPS has shone a light on the wider automotive network and highlighted how interconnected are the different OEM logistics operations, with shared suppliers, transportation companies, crossdocks and other facilities and assets. While this in itself if not a revelation, according to Brownlow it has encouraged vehicle-makers to move towards more collaboration.

“When we first dispatched these trackers out in the field and we started realising how intertwined our network was with other OEMs and suppliers, some of the issues that we found led to conversations with other OEMs,” he explains. This was the case with the stolen containers found in the warehouse, mentioned above, which prompted Nissan to reach out to its fellow OEMs and share its learnings.

According to Brownlow, the other vehicle-makers, and indeed some tier one suppliers, wanted to know how Nissan was accomplishing the tracking, how to implement something similar and what might be considered best practice.

He says Nissan is relaxed about sharing what it has discovered, rather than worrying about losing a possible advantage over competitors.

After all, states Brownlow, “These tech companies are out there courting other OEMs like they were us… this type of information that the tech provides is being shared openly, so it’s out there for everybody to use.”

Brownlow himself is keen to encourage wider interest and further collaboration, and feels there is much more that can be accomplished with tracking technology.

“As large and interconnected as the automotive supply chain is, we won’t solve some of these issues by ourselves,” he states.

Future applications

Brownlow believes that one of the key issues facing OEMs today is the need to work out how to make the most of the multiple technologies that are now “coming of age”, whether GPS, Bluetooth, RFID or something else.

“How does all that tie together [and] how do we capitalise on the data it’s giving us? I still think that there’s a lot of opportunity with these tools to drive efficiency and I think we still have a lot of runway left in that regard,” he states.

Brownlow says having a global supply chain with numerous assets in between facilities means that tracking technology will increasingly be used in future to provide visibility on where those assets are located between different points in the supply chain. Although Nissan’s recent project involved GPS, he notes that RFID is being deployed in some situations by both OEMs and tier suppliers.

He suggests that further possibilities could include, in the context of sea freight, tracking technology potentially enabling a seasonal change from reefer to dry containers based on temperature data. Or, the shock-recording capability could help to address quality issues by identifying cases where parts are damaged during the connection of railcars.

“I think from where we were four to five years ago to today, there has been a huge realisation of what the dollar amount is associated with packaging, the disruptions it can cause to the supply chain and effect on part quality” – Anthony Brownlow, Nissan North America

Moreover, it could facilitate changes in supply chain organisation. “[With] the visibility this is giving us, how do we structure our existing teams to process and capitalise on the new data streams that are available to us at Nissan and automotive [more generally] that’s coming in from this technology?” asks Brownlow.

“In this industry there’s a lot going on off-campus that has a significant impact on the bottom line. Our plan is to use today’s technology to pursue those improvements,” he adds.

In Brownlow’s opinion, packaging has moved up the agenda for vehicle-makers in recent years, and he says it is more commonly discussed and a bigger focus for OEMs now that the value of these assets is clear.

“I think from where we were four to five years ago to today, there has been a huge realisation of what the dollar amount is associated with packaging, the disruptions it can cause to the supply chain and effect on part quality.”

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet