As the UK approaches the decisive moment in its struggle to leave the EU, after three years of debate and negotiation, now seems like a very good time to take a look at the state of the country’s automotive industry in the run up to Brexit. No doubt there will be some changes – quite possibly drastic ones – to sales, production and export figures once the UK is finally out of the EU, so an update will surely be needed in the coming months.

One of the reasons why industry associations have been fighting so hard to avoid a situation in which the UK “crashes out” of the EU with no deal is because existing automotive manufacturing, logistics and sales activites sprawl across both sides of the Channel.

Some of the components among the approximately 30,000 which go into the production of a single vehicle currently cross the border not once but multiple times during the subassembly process before reaching their final destination – something which could become highly problematic with new customs procedures and the anticipated delays at ports and on the roads.

At the moment, around 1,100 trucks per day import components from Europe to the UK in support of engine and vehicle production operations, amounting to a total value of £35m ($45m). Moreover, those parts feed into just-in-time manufacturing systems honed over the course of decades which now have little if any leeway for delays and disruption.

Of course, the traffic is not all one way; heading to Europe from the UK are parts worth £5.2 billion per annum, including £2.9 billion worth of engines.

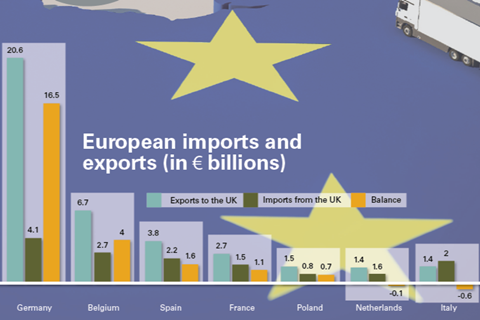

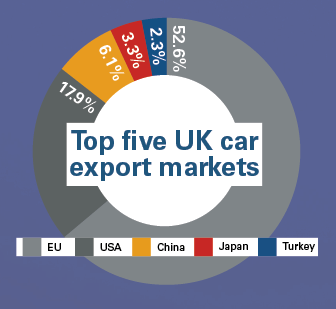

As for finished vehicles, here also there is huge interdependency between the two markets, which trade 3.3m vehicles each year. While roughly 70% of new cars on UK roads originate in the EU, 80% of cars made in the UK are exported to the EU. The UK is a key market for the EU, especially members such as Germany, but the EU is also the biggest market for the UK, taking more than half of its finished vehicle exports (see pie chart below).

Cost of contingency

Earlier this year, the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) estimated that delays in shipments of parts could cost the industry up to £50,000 per minute. For this reason, the UK automotive industry has now spent a massive sum – at least £330m by July this year – on stockpiling, reserving warehouse capacity, investing in new logistics systems and implementing other contingency measures.

That raw figure, creeping up towards half-a-billion pounds as the months go by, is significant enough in itself, but at the SMMT’s half-year briefing its CEO, Mike Hawes, suggested that automotive companies in the UK were spending money on contingency planning instead of technological investment, which could have implications for the country’s place in the development of future mobility. The UK is already lagging behind other nations in the region when it comes to developing an electric vehicle supply base, especially key players in Central and Eastern Europe.

As noted, the UK currently exports billions of pounds worth of automotive technology to Europe, including engines – the most complex assembly in the vehicle. The automotive industry is a mainstay of UK exports and is responsible for just over 14% of the total. As the industry progresses with its transition to an electric, connected and autonomous future, both government and industry in the UK will want to keep abreast of that trend.

Opening or closing?

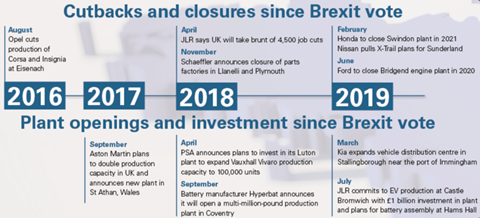

Since the Brexit vote in 2016, many in the industry have feared that the decision to leave the EU would adversely impact investments in the UK automotive industry, knowing that it could also mean leaving the single market and the customs union, which are vital to frictionless trade. These would be permanent changes, unlike the short-term disruption of delayed shipments. Under such conditions, it could well be difficult for an OEM to justify manufacturing vehicles in a UK plant for the EU market, rather than at a factory within the bloc.

UK manufacturing operations have up to now been valued for their skilled workforces and high levels of efficiency, which in some cases led to them acting as benchmarks for the wider organisations. For the Japanese OEMs, the UK was also regarded as a foothold in the European market and the country welcomed a series of arrivals in the 1980s and 1990s, leading to almost half of all UK automotive production coming from Japanese brands.

One example would be Nissan’s plant in Sunderland, which has received millions of pounds of investment since launching in 1986 and at one point was turning out half-a-million cars per year. The OEM has since cancelled plans to make the X-Trail in the UK and stopped producing its Infiniti models there.

At the time of the announcement in February this year, Nissan said that its change of plan regarding the X-Trail had been made for “business reasons” but admitted that “continued uncertainty” over Brexit had played into the decision. The halting of Infiniti production, announced the following month, was described as being part of a wider restructuring and withdrawal from western Europe.

Merciless economics

Other OEMs, including Nissan’s compatriot, Honda, have also announced withdrawals from UK manufacturing facilities (see timeline above) and in general these have been represented as simply one element of broader European or global strategies, with company statements denying that Brexit lay behind it. However, in the merciless economomic environment in which vehicle-makers operate today, it is hard to believe that the adverse effects of Brexit – now and in the coming years – were not a big factor in these decisions.

In addition to withdrawals from existing manufacturing operations, there is the likelihood that the flow of new investment is starting to slow down as companies shy away from the risk of putting their faith in post-Brexit Britain. The SMMT’s Hawes noted that by the middle of the year only £90m had been invested – a figure that included £23m of goverment support for EV programmes. He said the UK automotive industry normally attracts around £2.5 billion per annum, and described the drop as “precipitous”.

However, it is far too early to write off the UK as a good place to do business and the country has attracted investment from OEMs and tier suppliers each year since the Brexit vote (see timeline). In particular, the SMMT figure did not include Jaguar Land Rover’s commitment to spend £1 billion at two of its UK plants for EV production, including battery assembly – a decision that was announced in July. The final total for the year will show whether or not the country is maintaining its usual level of investment – for now.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet