The repercussions of Covid-19 continue to disrupt the automotive supply chain in North America, not least in the disruption caused to inbound container freight and the serious shortage in the supply of semiconductors. Marcus Williams reports

Available capacity in ocean freight is currently very tight in certain regions. The surge in cargo movements that followed the first wave of the coronavirus lockdowns in China has met with restricted capacity in the distribution network. That has been caused by a displacement of containers and tighter capacity at inland warehouses and distribution centres. Added to that are ongoing restrictions on international travel caused by the pandemic, which have reduced aircraft hold capacity.

As previously reported, the aftermath of the first wave of the coronavirus disrupted ocean container shipping, especially between Asia and North America. As global production of non-essential items ground to a halt, shipping capacity was cut. However, when demand rebounded as lockdowns were eased the industry was unprepared for the demand in capacity. The recovery in consumer demand coincided with increases in manufacturing, notably a stronger than expected resurgence in automotive production.

Container congestion

The resulting problem is seen clearly in the port congestion currently troubling the US west coast ports. At the time of publishing there were 29 full container vessels anchored off the ports of Long Beach and Los Angeles waiting for terminal space to unload. This is because fluidity and velocity – the two things that maximise terminal capacity – have been compromised, according to Dr Noel Hacegaba, deputy executive director and chief operating officer (COO) at the Port of Long Beach.

Currently, the average dwell time for containers at Long Beach port is well over four days and has been closer to six. That is triple what it is normally, the reason being the supply and capacity misalignment directly resulting from the Covid shutdowns in the first half of 2020.

“What happened was that in 2020 we [very quickly] transitioned from doom and gloom to fast and furious,” says Hacegaba. “In the first three or four months of the year the market outlook was very pessimistic, so the supply chain reacted by not planning for additional capacity. But when manufacturing reopened in China and the manufacturing machine resumed operations, the cargo started coming in and the supply chain was not ready for it.”

As Covid-19 swept across the world it affected manufacturing and supply in different ways. In the early part of 2020 manufacturing was halted in the Chinese industrial base of Wuhan, where a significant amount of automotive production is centred, and closures spread out from there to wider Asia.

Fewer containers of goods were moving across the Pacific to North America, where manufacturing was still going strong. That meant there were fewer containers for North American manufacturers to export their goods overseas.

When North America was later locked down, manufacturing was slowed, including automotive, and certain sectors of the economy were restricted because of their capacity. That did not hamper purchasing as e-commerce flourished, creating more demand for inbound goods at the same time that China was resuming full production.

The result was that for the first six months of 2020 the west coast ports were moving lower volumes but by the summer there was a strong rebound. Hacegaba says that the port started setting monthly records in terms of container units (or TEUs) processed.

“What is interesting about that is we ended the calendar year in Long Beach with our best year on record,” he says. “We had 8.1m TEUs, which represents a 6% year-over-year increase. That shows you that the last six months of the year were so strong that they offset the first six months and catapulted us to our best year on record.”

Velocity vs volatility

The Port of Long Beach has been working hard to deal with the rebound and handle the congestion as part of its STOR strategy, the acronym standing for short-term overflow resource. It has made an additional 40 acres (16 hectares) available for storage to get containers off the terminals, helping with fluidity and velocity.

Similarly, the Port of Los Angeles has been looking to secure additional capacity to relieve the pressure on marine terminals. At its last press conference, the port’s executive director Gene Seroka said it had a blueprint to get more chassis off the terminals to neutral sites near the dock and in doing so opening up an additional 50-80 acres (20-32 hectares) of terminal space.

“We need to be able to scale up when a surge hits, whether it be assets or staffing,” said Seroka. “And then when we have to rebalance that scale in more normal times, or even slower cargo volume, like we witnessed in this past spring we must be able to rise to that challenge.”

Like LA port authority, Long Beach has a priority to get its waterfront employees vaccinated against Covid.

“Their health and wellbeing is critical to our ability to move those containers from the port as soon as possible,” says Hacegaba. “So that’s what we are working on as well. We are advocating at all levels of government and trying to get our waterfront workers vaccinated as soon as possible.”

Port authorities along the US west coast along with the ILWU (International Longshore and Warehouse Union) signed a letter at the end of last year to the governors of Washington State, Oregon and California urging that vaccinations for waterfront workers be made available as soon as possible.

With these measures in place the ports looks set to rebalance flows in the next month. Hacegaba expects the influx to decrease following the Chinese New Year holiday, when there is typically a lull in imports. That holiday starts on February 12 and runs for 16 days.

[Read the full interview with Dr Hacegaba]

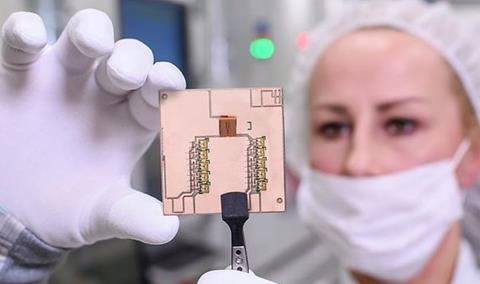

Chip to shore

What may impact the automotive industry for longer, however, is the shortage in the supply of semiconductors, which are used extensively throughout the electronics of a vehicle. The shortage in the supply of these microchips, which again stems from the Covid pandemic, is having far-reaching consequences for the production of parts and vehicles.

The shortage of semiconductor components – specifically integrated circuits (ICs) such as microcontrollers (MCUs), and application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) – is the result of a perfect storm, as the automotive industry experienced greater fluctuations in 2020 than any other industry buying semiconductors. At the same time, high demand from other industries led to capacity constraints in semiconductor facilities. The recovery in car sales and factory output that followed was faster than projected across all regions, driven by pent-up demand during the lockdown period.

While some are understandably reticent on the issue, most major OEMs appear to be affected by the impact of the supply shortage.

Fiat Chrysler Automobiles (FCA), which is merging with Groupe PSA into the newly formed Stellantis, has felt the impact on Chrysler production across North America. The company says it has been working closely with global supply chain network to manage any manufacturing impact caused by the global microchip shortage.

“As a result, we have taken the decision to delay the restart of our Toluca, Mexico plant, which builds the Jeep Compass, and schedule downtime at our Canadian plant in Brampton, Ontario, which builds the Chrysler 300, Dodge Charger and Dodge Challenger,” says a spokesperson for Stellantis. “This will minimise the impact of the current semiconductor shortage while ensuring we maintain production at our other North American plants.”

Toyota Motor North America, meanwhile, says it is continuing to evaluate the supply constraint and develop countermeasures to minimise the impact on production for the near term.

“At this time, the global supply shortage primarily impacts production of the Tundra, manufactured at our Texas plant, with components also produced in our Alabama, Tennessee and Missouri operations,” a spokesperson told Automotive Logistics, adding that Toyota did not expect any impact to employment at the moment.

While BMW says there has so far been no impact on production, its North American operations are maintaining constant communication with its suppliers on the issue.

“Our aim is to continue to secure supplies to our plants,” said a company spokesperson. “We have ordered the required volume for 2021 on time and expect our suppliers to deliver according to contract in line with the orders.”

Speaking for the parts suppliers, the Original Equipment Suppliers Association (OESA), reports that the shortage of semiconductors for electronic components used throughout the vehicle has led to a number of companies reducing volumes or announcing production downtime.

“Automotive component suppliers are working with the semiconductor suppliers and the wafer fabrication facilities to ensure capacity is in place to support the volume needed for the automotive industry,” says Julie Fream, president and CEO of OESA.

Covid crisis

However, is it merely a question of time before production is more widely affected given how dramatically the automotive sector has been hit by the shortage? Even modest estimates put the bottleneck in supply lasting anywhere between six and nine months and it is hard to immediately estimate how Taiwan’s commitment in the last week to prioritise supplies for the automotive industry will affect this shortage.

Tier one supplier Continental says that capacity shortages at the semiconductor suppliers are attributable to the slowdown in the first half of 2020 because of the coronavirus crisis.

“The automotive industry experienced greater fluctuations in 2020 than any other industry buying semiconductors,” said a Continental spokesperson. “Furthermore, high semiconductor demands from other industries led to capacity constraints in semiconductor fabs [fabrication plants].”

North America’s biggest tier supplier, Magna International, adds that coming out of the Covid shutdown into a strong resurgence for automotive production meant it was seeing signs of semiconductor chip shortages.

Tier one supplier Bosch says that the chip shortage was exacerbated by delays to one semiconductor manufacturer’s investments in expansion and production increases because of the coronavirus, resulting in significantly fewer chips being supplied.

Circuit breaker

The rise and fall of the automotive integrated circuit (auto IC) market shows just how constrained supply became. There was a dramatic shift away from automotive in the first half of 2020. According to market analyst VLSI Research, market share peaked at 10.4% in the last week of December 2019 but had fallen to a low of 3.6% in the week of May 8, 2020.

“Auto IC sales total dropped 44% over this period,” says Dan Hutcheson, CEO of semiconductor market research agency VLSI Research. “In contrast, total IC sales were up by 4% over this same period. The IC market was making a dramatic shift away from autos in the first half of 2020.”

That in turn meant that capacity at semiconductor supply was reallocated to other industries during the period.

“At the same time as the automotive standstill, the pandemic spurred an increase in demand for home computing and networking equipment, and the semiconductor manufacturing plants had to pivot to these other markets in order to maximise fab utilisation and successfully navigate economic headwinds,” notes Bettina Weiss, chief of staff and global smart mobility lead at Semi, the global industry association representing the electronics manufacturing and design supply chain.

The strong recovery in the automotive industry in North America, driven by pent-up demand during the lockdown period, meant OEMs were caught short.

According to Hutcheson this was most likely down to the automotive companies drawing from inventories of unbought microchips during the slump, which then ran out.

“It is the auto companies themselves who caused this by slamming on the brakes, locking up all four wheels, and sending semiconductor companies off the road without so much as a flat spot,” says Hutcheson. “The latter only responded to this panic like they are supposed to: protecting shareholder value by diverting fab capacity to other markets where it was needed.”

The supply shortage affecting North America is made worse by the problems in shipping capacity in air and sea (outlined above) because currently only 12% of global semiconductor manufacturing capacity for the North American market is local.

“Unless significant steps are taken, that share is currently forecasted to decrease,” says Bettina Weiss of Semi. “Focussing in on global 300mm wafer capacity for the most advanced semiconductors, nearly half of the capacity share in 2020 was concentrated in Korea and Taiwan, at 26% and 23% respectively. The US has about 10% share, while China has almost 14% and Japan has 16%.”

[Read the full interview with Bettina Weiss]

Better visibility

One thing this disruption has made clear is that better visibility of the supply chain is needed by parts suppliers and OEMs alike, a point made clear by another of North America’s leading parts suppliers – International Automotive Components (IAC) – at a recent live webinar, hosted by Automotive Logistics.

Kelly Bysouth, chief supply chain officer at IAC, said the company spent the majority of 2020 in crisis management mode, dealing with inventory, monitoring accounts payable activity and ensuring stability of supply once production started back up after the first wave of disruption.

Bysouth said it was important to understand how its sub-suppliers were able to deal with the changes going on in the industry. Specific to 2020 and the pandemic she said it was important to ascertain whether they were able to start back up when the industry did in the third quarter.

“Then, how do we effectively illuminate the condition of the supplier network? We have a pretty good view of our tier one suppliers, but how do we look further into the supply chain to understand potential risk that may be under the surface?” she said.

With that information it is crucial to identify alternative sources of supply, something that is more easily said than done.

“A lot of the parts that we buy in the automotive industry are specific engineered parts and a lot of those parts require lengthy lead times to tool up,” she noted. “We may be able to identify alternative sources of supply but how do we deploy those effectively?”

That also applies to the movement of parts across the globe, something that has taxed the automotive industry over the last 12 months. If problems with ocean and air freight capacity are likely to continue through 2021, the industry needs to be working hard to find alternative options to move parts, including semiconductors, to assembly. To do so the industry needs to have a much clearer view of the integrated supply chain to identify, react and take control of the disruption.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet