Carmakers, logistics providers and tier suppliers joined the heads of China’s leading trade associations in Shanghai this year to assess the sweeping changes taking place in the country’s automotive market. As regulators seek to support business during the slowdown, trade upheaval continues but so does the growth in digitalisation and new vehicle technology, which are reshaping the automotive supply chain in China and beyond. Marcus Williams reports from the Automotive Logistics Global Shanghai conference

China’s automotive industry is in a new phase of more modest growth, and carmakers and their logistics providers are using the slowdown in output to look at improving quality, reducing costs and making processes more efficient. At the same time the country is pursuing its Belt and Road Initiative, a comprehensive government policy aimed at developing infrastructure to support global trade on land and sea, with rail between China and Europe playing an increasingly important role for inbound and outbound transport alike.

China has also made some important changes to its trade and ownership models, lowering imports and revamping its shareholding regulations to enable foreign carmakers to have more than a 50% share of China-based businesses.

Finally, China is also looking at being the world’s number one producer, exporter and user of new energy vehicles (NEVs), which brings with it a range of complex logistics considerations, including the safety and security of lithium battery supply and the regulatory standards to which foreign imports must comply if they are being moved to China.

Better year for smaller business

Figures from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers (CAAM) show that production totalled 27.8m units last year, reflecting a 4.2% decline on a year-over-year basis. Sales, meanwhile, were at 28m units, reflecting a 2.8% decline on the same basis. China has maintained an annual rate of sales around 30m but the forecast is for lower annual sales in the coming years, a consequence of such a sustained period of high output.

The decline is also the result of structural changes to the economy brought about by China’s financial risk control (or deleveraging) policy, which was first introduced in 2008 but which has hit a number of small-to-medium automotive companies because of the difficulty experienced in securing loans.

“Many car buyers are those that work in SMEs and they suffered last year because of the deleveraging financial policy,” said Xu Changming, vice-president of the State Information Centre. “Last year private businesses were not performing very well and that explains why there were fewer buyers.”

Consumers of more modestly priced vehicles now account for 70% of the overall car buying market and it was this category of consumer that was most affected by China’ s economic policy, said Xu. Cars priced below RMB 80,000 ($11,900) showed a drop in sales growth of -30% compared with those above RMB 200,000, which only dropped by -3.6%, he explained.

Last year tier three cities, which are predominantly populated with private Chinese businesses also showed a drop in growth of -10% compared with the -1% decrease in the tier one cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, which are those with governmental or multinational employers.

Economic optimism

China’s GDP was 6.4% last year, down from 6.8% the year before, though that is still a strong rate and speakers at this year’s Automotive Logistics Global Shanghai conference felt there were several reasons for the automotive industry to remain positive.

Xu claimed that current government economic policy was a cause for optimism and that the macroeconomic drive of 2019 was to reduce financing costs, something that had been contributing to a more favourable business environment for the small-to-medium private companies and entrepreneurs.

“Last year the policy was deleveraging but this year the macro-economic policy is the opposite and it is much more pro-active in terms of financing,” said Xu. As of this year all banks are required to lend to SMEs and Xu added that it took between six and nine months after financing was made available for the impact to be felt by the affected companies.

Cai Jin, vice-president of the China Federation of Logistics Purchasing (CFLP), also pointed to China’s more steady growth path and highlighted encouraging signs including an uptick in the Purchasing Managers Index to above 50%. He saw the development of the NEV market as a source of growth as it matured, though existing subsidies to incentivise purchases of NEVs are due to be withdrawn after 2020.

However, Cai said there was a need for the car industry to develop along with this new market and that transitioning to a modern supply chain would be “critical”. He said that when it came to the scaling of costs, China had reached a maximum and would need to see a reduction, especially for logistics (read more).

Government coordination

Economic policy aside, the government was also held to blame for a lack of coordination when it came to supporting vehicle imports. Wen Rui, director of logistics, for VW Group in China, pointed out that the actual transport of the vehicles only accounted for 50% of the job, the other half of the time being taken up with communicating and dealing with various government agencies.

[mpu_ad]That is because a lot of certification from many different government bodies is required when importing a vehicle to China. Everything from battery registration and on-board diagnostics certification to rim codes and taxation, has its own administrative procedure and each requires the submission of a raft of different documents. Furthermore, any error in the submission of that information is very difficult to rectify, according to Wen, and can lead to costly delays.

“It takes a lot of time, manpower and effort to deal with government requirements,” said Wen. “We hope there will be some sort of coordination within the government agencies by themselves.”

Wen said carmakers were looking for a one-stop service where they could simply submit one package of data for the different government bodies, from which each could extract what was needed.

Peng Fei, deputy director, Shanghai Customs Tariff Department, indicated that there was a move in that direction. As a product of the most recent round of reforms to the customs and tariffs systems in China there were now two customs administration bureaus: the Tariff Bureau and Risk Prevention and Control Bureau. Peng said that in the future only the Risk Control and Prevention Bureau would be able to demand an inspection of inbound goods when in the past many different bureaus could make the request.

“Customs will look at declaration and give two permits, one to import and one to grant access to the market,” said Peng. “This is meant to ease the process.”

Peng explained that the Commodity Inspection Bureau had been merged into the Customs Bureau. If a commodity comes up to quality standards it is given the permit for access to the market.

“The customs house will have one touch point rather than the companies having to have several touch points,” said Peng. Nevertheless, Wen said he had yet to see any signs that the customs and commodity testing agencies were properly integrated.

There also needs to be greater integration of government bodies dealing with tariffs and taxation.

“For import duties they want you to declare a CLF (cost, insurance and freight) price as high as possible,” said Wen. “You want your profitability to be maintained at a reasonable level but taxation authorities think differently. They should talk to each other. The tax authority will challenge you that the CLF is too high while the customs office will say that your CLF is too low and won’t be able to charge you a high import duty.”

Special bonded zones

Carmakers are also eager to get a clearer view from the General Office of Customs Management on its proposed incentive policies and the establishment of special bonded zones for vehicle imports, a change in policy that Wen said VW Group was keen to exploit. At the beginning of the year, the State Council announced that it would be introducing measures to bring its special bonded zones at the ports in line with international standards to promote trade and investment.

Qin Meng, senior vehicle allocation manager at Porsche, agreed and said that since the initial announcement there had been no confirmation from the government, which was making the schedule tighter as requests for imports through those bonded zones increased.

As reported elsewhere, Porsche is now moving vehicles by ocean and rail in to China, and last year the country accounted for 31% of all Porsche deliveries (with the majority delivered by ocean).

Qin said that currently only the ports have the licences for bonded zones but that port cities, including Tianjin, Guangzhou and Shanghai, had their bonded zones at the airport, which incurred a much higher cost.

“If it is an airport-based bonded zone then we have to apply for the import declaration at the airport,” she said. “But import customs might not be that mature in terms of the professional expertise compared with the [maritime] ports.”

Wen said that, in line with the industry’s new focus on refining existing logistics processes and looking at new ones, VW Group would be concentrating on streamlining its procedures and process. She said now was the time to cut costs and improve efficiency, but reiterated that there needed to be corresponding institutional changes.

“We need the market to play its role, the market reform is a top-down approach, but it is anyone’s guess as to the extent an organisation’s department can feel the strength of the reform,” she said.

Roller coaster year for imports

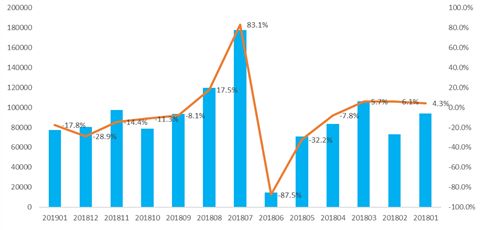

In terms of import policy more widely, there was a significant reduction in tariffs in 2018. From the beginning of July 2018 China lowered the import duty on foreign-made cars from 25% to 15%, with tariffs on automotive parts dropping from around 10% to 6%. However, the trade dispute with the US has complicated the picture and Wu Sonquan, chief expert at the China Automotive Technology and Research Centre (Catarc), described the pattern of import volumes as resembling a roller coaster.According to figures from Catarc, in April last year import volumes started to fall and rise more erratically. “In May it nose-dived, with a drop rate around 90% but after July it began to pick up and this was largely because of the trade war with the US,” said Wu (see table).

He went on to say that a combination of factors including the China-US trade war, China’s double credit system, and its initiative to develop NEVs, meant the scale and structure of imports for cars in 2018 had changed a lot – but he also forecast an increase in the volume of imported cars, up on the 1m that were brought into the country last year.

Richard Wang, vice-director of Sinomach Automobile, noted some other factors affecting imports related to measures taken to regulate stock and demand, which led to a disconnect between supply and demand, since when companies have been destocking.”

Wang explained that 1.18m vehicles were imported in 2018, which was down almost 9% on the previous year. In terms of sales of imported vehicles, dealers moved 854,000, a drop of 5.6% year-on-year.

Fuel consumption and NEVs

One factor that could affect future imports to China relates to its regulation on fuel consumption, which will determine the future development and product mix of foreign vehicle-makers. By 2020 Chinese regulations stipulate that the average fuel consumption limit for passenger cars should drop to 5 litres per 100km (down from 8.2 litres per 100km). That will drop again further in 2025 to 4 litres per 100km.

“This is a mandatory requirement and so most of the carmakers from outside of China will have to seek to meet this rigid requirement by the Chinese government,” he said.NEVs, meanwhile, have proven very popular in China, thanks in part to the incentives that customers get if they buy one, and China’s development of the NEV market has made it the global leader with 50% of total global sales. Wu said that foreign carmakers would have to comply with the rules on NEV production if they wanted to benefit from existing NEV credit schemes.

China is aiming to become the world’s leading exporter of vehicles, something that its lead in the NEV market and its dominance of the major material mining sources in the world will help support, though only 3% of vehicles made in China are currently exported. Wu said that this would change and that foreign carmakers would use China as an export base.

“The change in the policy on foreign-funded carmakers in China and the improvement of core competencies of the Chinese-funded companies will be the decisive factors over the future expansion of exports for Chinese cars to the outside world,” said Wu. “You will have noticed that many foreign companies are talking about whether it is possible to expand such a business in the future, such as JLR and BMW.”

Wu said the change of international trade rules will make China more open and that this would in turn facilitate an increase in imports and exports. He forecast that tariffs would drop further and that international demand for Chinese-made cars would increase.

The Automotive Logistics Global Shanghai conference is part of the global Automotive Logistics series of events.

The next event in the series is Automotive Logistics Global Munich, (formerly Automotive Logistics Europe) which takes place on July 2-4 at Infinity Munich in Unterschleißheim