GM’s global purchasing chief, Jeff Morrison, has forged new partnerships with suppliers across chipmakers, battery materials and logistics providers to create more stable, resilient operations. Now his team wants to regain even more control – especially in vehicle logistics, in which the industry is facing many bottlenecks.

Jeffrey Morrison is modest about what he and his teams have achieved since he took over as vice-president of global purchasing and supply chain (GPSC) at General Motors in spring of last year. Responsible for partnerships with direct suppliers and service providers across the carmaker’s global operations, Morrison’s biggest priority so far has been to bring a semblance of normality back to the supply chain, including parts availability, production scheduling, logistics costs, labour and dealer shipments.

“The focus has been on how we can get back to a more normal, laminar flow,” he says.

In a time of great transformation, this might sound underwhelming: more ‘back to basics’ than ‘revolution’. However, the path to ‘normal’ in the automotive supply chain has been twisted and tortured by any measure. Whether through lockdowns in China, or continued chip, material, logistics and labour shortages, GM’s supply chain teams have had to constantly pivot locations, expedite shipments, or work with suppliers to secure staff and improve service levels. More recently, finished vehicle logistics capacity has been a major issue.

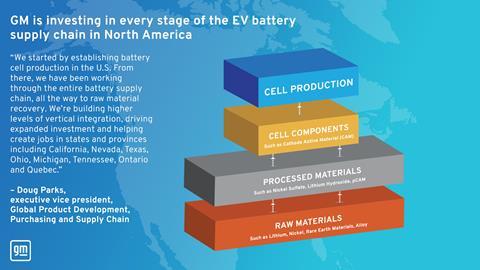

But alongside the firefighting, Morrison and his team have been realigning GM’s supply chain and planning operations in important ways. Under his watch, the company has forged strategic partnerships in semiconductor manufacturing, creating direct capacity and relations with chipmakers for the first time. It has invested in battery production and critical materials, partnering with companies to secure cathodes, expand material processing capacity and establish lithium mines in the US. GM has also sought to expand visibility and connectivity with upstream suppliers through supply chain mapping and advanced analytics.

The shifts in GM’s purchasing culture are notable, too. Whilst cost reduction remains a priority, Morrison’s teams have clear goals to improve supplier relations (printouts of the carmaker’s score in influential supplier surveys hang across the GPSC offices). Internally, GM’s procurement and logistics teams have worked more closely with engineering and manufacturing teams, for example to simplify and standardise chip requirements, and better coordinate on sourcing and production decisions.

These projects reveal the true scale of Morrison’s ambitions for GM’s global supply chain. “We want to control our own destiny,” he says. “We are establishing partnerships to secure the material and capacity that we need.”

There has been progress, with some parts of the supply chain starting to normalise – to a degree. Chip supply has improved, allowing carmakers to ramp up production and fill backorders; in the US, GM has increased its sales and market share lead. Material availability and inbound logistics are more reliable, with more stable pricing in container shipping, trucking and air freight.

GM’s electric vehicle and battery supply chain plans also remain on track. Morrison confirms that the carmaker has secured enough battery cell capacity and materials to meet its goal of producing 1m EVs per year in North America by 2025.

However, difficulties and risks remain. Chip supply is still “fragile”, says Morrison. The ever-increasing value of semiconductors in connected and electric vehicles could create further supply bullwhips, with mismatches in the allocation of chips assigned to OEMs from suppliers. Meanwhile, it will take years to build up supplies of critical materials and processing capabilities for battery production in regions like North America; today, there is still a strong reliance on companies and capabilities in China, for example.

More immediately, a crisis in finished vehicle logistics capacity is disrupting customer deliveries and putting production schedules at risk for GM and others in North America (it’s an issue that OEMs in regions like Europe are experiencing, too). Shortages of global ocean ro-ro capacity, and especially network and scheduling problems for vehicle rail services, are extending lead times, and making it harder to move inventory just as GM is finally able to run consistent build schedules again.

“Our issue is really on finished vehicles, and we’re not alone in that. If you were to ask me what my top issues are, it’s in the top five,” says Morrison. “And if you were to ask my CEO [Mary Barra], it’s one of her top five issues to be able to move the vehicles that we build.”

That top-level attention, however, is leading GM to address underlying problems in vehicle logistics, much as Morrison and his team have recently done with battery materials, connected vehicles and software, and semiconductors.

“Our issue is really on finished vehicles, and we’re not alone in that. If you were to ask me what my top issues are, it’s in the top five. And if you were to ask my CEO [Mary Barra], it’s one of her top five issues to be able to move the vehicles that we build.” -Jeff Morrison, GM

Help needed fast in finished vehicle logistics

There are multiple causes for the vehicle logistics capacity issues in North America, including network changes, labour shortages and underinvestment from vehicle manufacturers and logistics providers. Morrison points to the volatile swings in vehicle production schedules and logistics flows since the start of the pandemic, from last-minute shutdowns to ‘build shy’ production – vehicles assembled without certain components that need rework later – that require extra transport moves and storage.

“Logistics loves predictability and constant flows, and those things have not occurred,” admits Morrison.

He also points to significant production and logistics network changes, including rising imports from Asia, as well as Mexico, both of which have put more pressure on rail services and railcar returns, which are managed by pooling provider TTX. Labour shortages and other scheduling changes have further compounded the issue.

“We’re at a point where customer demand is still very strong, inventory at dealers is still low, and we’ve got vehicles that are basically built and ready to ship that we can’t move,” Morrison says.

In the short term, GM is looking for any “self help” that the logistics network can offer to get vehicles moving. That has included shifting more volume to trucking providers, for example. It has used more containers to ship vehicles around the world. Earlier this year, GM switched export volume from Mexico that would usually move northbound by rail to ocean shipments.

Morrison and his team, including executive director of global logistics, Renee Wawrzynski and executive director of global supply chain, David Leich, have been engaging with industry leaders and CEOs to understand how the carmaker can support solutions. He is clear that the company would make significant investments to take control of its destiny in this area, too. The clear preference, however, is to work with providers.

“We know that we are one of many players involved in these networks, and that many companies need to work together in the network to make it all happen,” he says. “But we are trying to understand how we can be better customers and partners, because we need to see improvements pretty quickly.”

Hear from the GM on controlling supply chain destinies

Jeff Morrison will speak at the 2024 Automotive Logistics and Supply Chain Global, September 24-26 in Dearborn, Michigan, in a fireside chat on how to best plan for optimised, secure supply chains cross-functionally and with partners. You will also hear from executive director for global supply chain at GM, David Leich.

A direct line to chip supply

GM’s success in dealing with other supply chain bottlenecks could point the way towards improvements in areas like finished vehicle logistics, too. One clear example has been in the semiconductor supply chain.

Whilst the chip crisis had multiple causes, Morrison identifies the historic lack of direct relationships and supply agreements between OEMs and chip suppliers. Chip suppliers have also traditionally supplied OEMs through allocation, usually through tier-1 or tier-2 suppliers – a model that is practically a dirty word for Morrison (he refers to it as the “A word”).

The model is complicated further by the automotive industry’s long product development, production and service cycles. Its electronic and computing architecture, meanwhile, has tended to standardisation, resulting in a high variety of electronic controllers in production, for example.

In this dynamic, even small mismatches in forecasting – such as those that occurred during the pandemic, when demand rose significantly for personal digital devices – can end up with wildly disproportionate impacts in production planning. With highly specialised materials and a limited number of suppliers, it has taken years to scale up production of automotive chips. It’s a situation that Morrison doesn’t ever want to repeat.

“If we have a node that we know is constrained and shared with others, I do not want to ever be in a position where the suppliers can only produce 70% of what the industry needs, and I’m being allocated equal numbers to the rest of the industry. I think it’s a bad formula.”

In response, GM has built more direct relationships with chip manufacturers. That has led to more direct supply agreements – including a dedicated corridor for specialised silicon chips from providers such as GlobalFoundries – but also a better understanding of product and engineering requirements on both sides. “It has been important to be more responsive in understanding what the semiconductor fabs need,” says Morrison.

GM also had to change the way it works internally, too. Morrison admits that the company lacked a core group of engineers and supply chain teams specialised in silicon, whereas it has now grouped together these experts into a centre of excellence to help shape and manage agreements. Likewise, the company has begun reassessing its product development and engineering to simplify electronics and software architecture wherever possible, especially to reduce the number of chips a vehicle needs.

Whilst GM has made progress, Morrison sees opportunities to drastically cut the number of components further. “As an industry, we’ve got to find ways to simplify. In talking to colleagues at other OEMs, we have circuit boards that might collectively use 500- or 600-part numbers today, whereas that could be narrowed to five or ten,” he says.

Identifying weak points in the battery supply chain

GM has also been applying lessons from semiconductors as it establishes its battery supply chain. It’s also an area that Morrison knew well even before taking on the top role in GPSC; he previously led purchasing for global electrified vehicle hardware development, including electric drive propulsion systems.

For example, GM has established a centre of expertise in battery supply across finance, legal teams, procurement, manufacturing, engineering and supply chain. The group has board support and is able to make fast decisions. This setup has enabled GM to develop complex financial arrangements and partnerships at pace, including equity investments, prepayments to key suppliers, loans and other agreements, says Morrison.

GM has been ramping up its battery supply chain over the past three years, including plans for three gigafactories in the US with its Ultium joint venture with LG Energy Solutions, and a fourth with Samsung SDI. Whilst the battery cell makers bring technology and advances in cell design, GM brings its production, procurement and logistical prowess to the equation. “You can see that everyone is trying to grow their footprint around the world with the same four or five battery cell partners, and these battery producers just don’t have that scope and breadth, but we know how to industrialise and scale plants,” he says.

As GM plans higher battery and EV output, it has also intensified its focus upstream on key materials, including for lithium, nickel, cobalt and manganese. But here, too, there are key lessons that the pandemic and chip shortages exposed. Morrison wants to better understand and map the upstream supply chain – including tier-2, tier-3 and above – to identify where dependency risks might be, for example a supply chain relying on just one or two sub-suppliers. “You may have many tier-1 suppliers who are sharing the same tier-3 or tier-4 suppliers, and those companies might have a risk profile that isn’t what GM wants,” he says.

Whilst the supply chain for critical materials is concentrated across global regions – some of them, like the DRC for cobalt, with poor track records in forced labour – sources are still relatively dispersed across regions, including countries that would classify as ‘allies’ and meet US government regulations. GM has identified a higher risk, however, in limited battery materials processing, which is highly concentrated in Asia and especially China, with a limited number of suppliers for battery grade materials that go into key components like cathodes and anodes.

That is why it has signed important agreements with Posco and LG Chem on cathode materials, as well as further contracts for nickel sulphate, manganese sulphate, and a range of lithium processing projects in the US and South America. GM is also one of the first OEMs to develop rare earth materials to attract EV magnet producers to the US.

“There is an intentional need that we need to develop an alternate network or alliance of not only the mining, but also the processing so that we’ve got a good, strong resilient value chain,” Morrison says.

Supplier relations: being transparent about changes ahead

For Morrison, supplier relations are strongly linked to supply chain resilience, which GM has made efforts to improve. One way has been through more transparency in cost modelling, which it is using upfront as a basis for negotiations. “That has enabled us to be more strategic and less transactional with suppliers, and to bring issues and discussions forward,” he says.

Along with measuring business, cost and delivery performance, GM also asks suppliers to rate its cultural performance. “Everyone from our commodity purchasing teams and all our key suppliers sit down at least once a year to talk about the scores. It ends up being this great, sometimes brutal conversation about how we can get better,” says Morrison.

Efforts to measure relations have started to pay off. This past spring, GM’s score increased ten points to 297 in the North American Automotive OEM Supplier Working Relations Index Study, an annual survey of suppliers conducted by Plante Moran on perceptions of six major vehicle manufacturers in the region. GM’s score, which ranked third behind Toyota and Honda, was among the most improved in the survey, ranking higher in supplier trust and in its collaboration with suppliers in product development, for example. The carmaker scored second overall behind Honda in overall OEM purchasing effectiveness.

GM has improved almost 30 points since 2020; it used to rank at the bottom of the index in the early 2000s. “We have put a ton of effort and energy into improving supply relationships,” he says.

Better supplier relations will be vital as the carmaker navigates a fast-changing, uncertain landscape, both in developing the EV supply chain and supporting suppliers in the transition away from internal combustion engines.

Morrison highlights, for example, how fast GM’s EV architectures are evolving. The carmaker’s current Ultium platform, for example, is designed with standardised single- and double-layer battery packs, with the ability to mix and match electric drive units between different size models, from smaller SUVs right up to the electric Hummer. But as technology develops, GM is turning more to silicon carbide inverters, which could enable faster charging and efficiency.

GM is also shifting its use of electronic switches and inverters, including moving from IGBT (insulate-gate bipolar resistors) semiconductors to silicon mosfets (metal-oxide semiconductor field-effect transistors), which can handle significant shifts between high-voltage and high-current signals. But the supply chain is still developing in these areas.

“We know that the capacity is not there for silicon carbide mosfets, but we along with others are going in that direction fact, so that is an area that we need to make sure we are securing,” says Morrison.

Should supplier capacity in areas like converters not develop quick enough, Morrison does not rule out building the technology in-house, as it has for electric drivetrains, which it will build at engine plants including Toledo, Ohio and St Catherines, Ontario. “We need to keep an open mind, and keep looking at where technology is leading us, and then make good decisions on how much we want to vertically integrate in those areas,” he says.

Ready to invest in ICE partners

Although GM is investing heavily in battery and EV supply chains, the company also needs to drive innovation across the ICE supply chain, the landscape for which in many ways is becoming even more complex for suppliers. The US and other governments are setting tighter emission and fuel economy standards as they set target dates to phase out ICEs, which means that GM and its supply base must invest significantly in these assets even as they are likely to decline in value and volume over time.

GM is also investing in ICE and hybrid products and production, which is still the main driver of its profits. In recent months, it has announced billions to retool and update plants for ICE products, including assembly plants in Flint, Michigan, and Fort Wayne, Indiana, and in an engine plant in Ohio. This summer, it unveiled the Chevrolet Traverse mid-size SUV, for which it has invested $500m at its plants in Lansing, Michigan, including adding a third shift to build the model and its siblings.

In response, GM needs strong partners to support these products, even as it ramps up EVs in parallel. Already, some suppliers are divesting or consolidating parts of their ICE business. “There’s tough work ahead in terms of managing that curve between capacity and plant closures, and the redeployment of people,” says Morrison. “We’re worried about that as there will be need for investment.”

GM is therefore working directly with suppliers looking to divest its ICE business and those who might be creating new divisions or entities to aggregate investment and R&D. “This way we can work to fill any necessary gap in capacity,” he says. “It’s something that we need to be great partners with strong communication as we go forward, because if we just leave it to the contracts to play out, we won’t get the right answer.”

“There’s tough work ahead in terms of managing that curve between [supplier] capacity and plant closures, and the redeployment of people [in the transition from ICE to EV]. We’re worried about that as there will be need for investment.” -Jeff Morrison, GM

GM’s greener supplier partnerships

Closer supplier relationships will play a major role in GM’s sustainability initiatives, including its goal to be net carbon zero across its operations and supply chain by 2040. Over the past two years, the carmaker has asked suppliers to join an ESG pledge that includes reporting through a carbon calculator from sustainability ratings group, Ecovadis. Suppliers reporting their emissions now represent around 90% of GM’s global spend, says VP of global purchasing and supply chain, Jeff Morrison.

From this data, the carmaker works with suppliers to make further emissions reductions. GM has, for example, struck agreements with most of its steel mills to produce grades of green steel; it has switched to renewable materials, and worked with suppliers to reduce energy consumption. Logistics network engineering, including consolidating freight, using greener transport modes and using sustainable packaging are also playing a role.

Such progress requires active engagement, however. In recent years GM launched an initiative called Energy Treasure Maps, whereby GM purchasing teams make onsite assessments at suppliers to identify where they can reduce waste and energy. The goal is to scale up these assessments. A few years ago, the team did eight in one year; last year, that increased to 80. Now, the purchasing and supply chain are exploring how to do 800 annually.

“We have to drive sustainability as a cultural priority throughout our supply base and let suppliers know that this is something that’s really important for GM,” Morrison says. “As we move towards an EV future, we want to make sure that we’ve got a clean supply chain to go with that, and we’re here to partner with suppliers and help them work through that.”

Time to get to know the supply chain better

Navigating partnerships and investments across GM’s supply chain will be complex. There are huge opportunities in areas such as battery materials and processing, however this technology is evolving at a far faster pace than traditional components and modules. That will require continuous exchange between suppliers, GM engineers and supply chain leaders.

Battery cell chemistries and pack designs are examples of this dynamism. Compared to today, Morrison expects a range of low-, mid- and high-energy density battery chemistries, each of which will require different levels of critical minerals. Alternative chemistries, such as lithium-ion phosphate, will also play a role. The entire landscape could change in the next few years, and that’s before more advanced technology like solid state batteries emerge at scale.

“That is why rather than overinvest in one chemistry, we want to have multiple partners that have the flexibility in their assets to do multiple chemistries,” he says. “It’s not easy to do, but our aim is to secure the amount that we need but give ourselves the flexibility to keep incrementing every two or three years as the technology develops.”

The dynamic will be similar across other components the supply chain, whether for inverters, magnets and silicon-based switches, or shifts in the carmaker’s electrical architecture away from discrete controllers towards a new set of chips and more centralised compute power.

Morrison’s advice to suppliers is to get to know the right experts at GM, whether in purchasing, engineering, logistics or manufacturing, as they will all be important to manage fast changes.

“If you don’t have those great relationships or partnerships with the GM team, start today,” he says. “It’s the companies that are really thinking about how we can create value and partner differently, and which are having the discussions with us about how to do that, that will have a great advantage going forward.”

The man in charge of GM’s global purchasing

As vice-president of global purchasing and supply chain, Jeff Morrison is GM’s top purchasing executive, with full responsibility for direct purchasing of material, commodities and logistics, a position he has held since April 2022. He reports to Doug Parks, executive vice-president, global product development, purchasing and supply chain.

Morrison has more than 25 years of experience in the global automotive industry and has been at GM since 2006, with roles in global engineering, procurement and logistics organisations in the US and Germany. Prior to his current role, he was responsible for GM’s global electrified vehicle hardware development, which includes overall electric vehicle propulsion calibration and driving performance. Morrison holds a master’s degree in business administration from the University of Michigan Ross School of Business and a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Investing in the long term: Interview series with GM’s Jeff Morrison, VP global purchasing and supply chain

- 1

Currently reading

Currently readingControlling destinies in GM’s supply chain

- 2

- 3

- 4

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet