Volvo Cars is on a mission to make its supply chain as sustainable as its electric vehicles, so it has combined procurement and supply chain logistics for greater clarity on the flow of parts, materials and vehicles. Kerstin Enochsson, head of procurement and supply chain, explains more

In the latest phase of its reorganisation of global operations, Volvo Cars took the decision to combine its supply chain logistics and procurement functions with a view to better addressing the challenges of a complex global supply chain.

To support that combination of functions, in October last year Kerstin Enochsson added leadership of supply chain and logistics to her existing role as chief procurement officer in a newly created role as head of procurement and supply chain.

Chris Godfrey, now head of operations planning and logistics, leading on Volvo’s global logistics across Europe, Asia and the Americas, reports to Enochsson under the new organisation.

The global automotive supply chain is a complex one and the advantage of combining procurement and supply chain logistics is the greater clarity it provides on the end-to-end flow of raw material through to the end customer, according to Enochsson. That includes visibility on parts and materials right down to the tier-n level, and the delivery of the finished vehicle to the dealer.

That visibility also provides more touchpoints in the flow of aftermarket parts, and provides a better and more informative service for the customer.

“It is an opportunity to get a proper end-to-end flow, with a planning engine next to it,” says Enochsson. “It’s about taking the learning from the current business and bringing it into the future.”

From the supply chain perspective, Volvo is now communicating with suppliers further upstream on such matters as raw materials for lithium batteries and wafers for semiconductors.

“Seeing end to end helps you to get greater transparency and manage risk, and then get higher efficiency,” says Enochsson.

Covid complications

The complexity of the global automotive supply chain has been further complicated over the last three years by the disruption caused by the Covid pandemic and the consequent repercussions in the supply chain, including the semiconductor shortage and global container misalignment. With semiconductors and crucial battery materials mainly coming from Asia, disruption at any point en route can cause significant production delays. Looking ahead, Enochsson says that linking procurement with logistics is a way of mitigating that disruption by giving a better view of landed cost and risk.

“You can talk about supplier footprint in a very different manner because it is not just who the supplier is but where the supplier is located,” she says. “So, if you see in the continental transport, for example, that it is extremely risky, then you might take different decisions for buyer locations.”

Enochsson says the closer combination of procurement and supply chain logistics is likely to catch on in the automotive sector more widely, especially given geopolitical risk factors. The war in Ukraine has had a big impact on parts supply, particularly wiring harnesses, and tensions between China and Taiwan threaten to impact semiconductor supply.

At the moment, the shortage in the supply of semiconductors is easing across the automotive sector and carmakers are getting a better overview of what is available and from where, meaning there are fewer surprises in that supply chain. Closer connections between carmakers and the semiconductor suppliers are going be essential as vehicles become electrified and connected, requiring more sophisticated chips in greater volume.

What is also important, says Enochsson, is that the supply of those chips is consistent and controlled. It need not be the supply of essentials such as semiconductors or lithium batteries that can threaten a production line, however. Production can be brought to a standstill by a seemingly insignificant part if there is not clear visibility along the supply chain to the sub-tier-one level.

Resilience and sustainability require a total view of the vehicle and its parts. Ultimately, that visibility is improved, and risk and cost exposure reduced, by regionalising more production, according to Enochsson.

“It is about staying true to where we are building the cars – regionalisation of the supply chain – then also about ensuring that outbound costs are under control and have a shorter distance from where we produce the cars to where we sell them,” she says.

Upstream connections

Resilience and sustainability are also helped by vertical integration, a growing trend among OEMs in the wake of the last years’ disruption, and in the context of geopolitical tensions. Direct contracts with suppliers provide carmakers with more certainty on securing parts and materials, rather than relying on suppliers that may have competing commitments with other customers. Legislation on localised production in Europe and the US is providing the grounds to support this.

Supply chain logistics evolution at Volvo Cars

Volvo’s reorganisation of its supply chain management (SCM) began in April 2020. The company made SCM a strategic inhouse function with a global footprint, with regional heads replaced by a functional management organised into divisions with global responsibility.

Inbound and outbound logistics were divided into two areas, one focused on operating excellence, driving high levels of performance and tactical improvements to the business.

The second function is now focused on strategy and network design, aimed at driving commercial savings and an optimised logistics network.

Outbound logistics is divided into a global Outbound Logistics Engineering and Strategy department and an Outbound Logistics Operations unit.

In addition, Volvo established Global Customs & Export Control, Lean Transformation of the Inbound Supply Chain and Global Parts Supply & Logistics units.

Under Kerstin Enochsson, procurement and supply chain are still part of Engineering and Operations, which also groups together R&D, Manufacturing and Quality.

Volvo is integrating more, notably in electric powertrain and related power electronics. “We are taking steps in the field of battery materials and electric powertrain, and also in the purchasing of silicon directly from providers” says Enochsson. “We have quite a few direct contracts with upstream players that we haven’t have before.”

That is particularly important in Europe, where a comparative lack of investment in processing and refining has left western nations in a vulnerable position. The supply of materials is still globally divided, especially when it comes to the raw materials for batteries and their processing.

Apart from the lack of lithium mining and refining, there is a lack of gigafactories and the region needs around 50 of them over the next decade if it is to establish its own battery EV supply chain and hit EV production targets.

However, there are positive signs of progress. Volvo’s biggest production plant in Torslanda, near Gothenburg, Sweden, stands to benefit from regionalised battery production. Swedish battery maker

Northvolt is already supplying Volvo production in Sweden and Belgium from its Northvolt Ett plant in Skellefteå, northern Sweden.

In terms of stronger vertical integration, however, Volvo has set up a joint venture company with Northvolt called Novo, and construction on a gigafactory is underway in Gothenburg, near the Volvo plant. The gigafactory will be begin production exclusively for Volvo in 2026. The new 50 GWh plant will make battery cells specifically developed to be used in next-generation pure electric Volvo and Polestar cars.

Last year, Northvolt also began battery recycling at its Hydrovolt joint venture plant in Fredrikstad, offering Volvo the opportunity to address the circular economy in battery supply.

Recharging the network

That vertical integration of the battery supply chain feeds into strong performance and competitive advantage. The development of battery EVs is a major focus for Volvo, with the goal of making 50% of the vehicles it sells battery electric by 2025, upping that to 100% by 2030.

“We are staying true to our electrification journey, even though there are some headwinds right now,” says Enochsson. “Our trajectory is super positive.”

In December last year 20% of overall Volvo Car sales were electric and more

than 40% of those were of the XC40 Recharge EV.

That success puts demands on the supply chain in a situation where battery materials need to be tracked to ensure quality, environmental impact and ethical standards, again managing risk through greater transparency on regional sourcing and supply.

Cutting the carbon

Sustainability, including the reduction of CO2, is at the forefront of Volvo’s agenda, says Enochsson. That goes not just for the production and driving life of EVs such as the XC40 Recharge, but also in terms of taking carbon out of the supply and transport of the materials and parts.

“Sustainability is as important as safety for us, and we have discussions with the carriers around CO2,” she says. “We are measuring it, we are trying to find better solutions with suppliers to reduce CO2 from movements.”

Again, planning to regionalise the supply of as much material as possible is a good way of cutting carbon from the supply chain. Volvo has clear carbon reduction targets that it establishes as a base requirement for contracts with logistics providers.

At the UN Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in 2021 (COP26), Volvo made a commitment to clean up the cars it is making and the supply chains supporting production. As part of its commitment to phase out fossil-fuel vehicles in leading markets by 2035, the carmaker committed to an internal carbon price of 1,000 SEK ($105) for every ton of carbon emissions from across its entire business, in line with its ambition to become a climate neutral company by 2040. Volvo has established an internal carbon price relating to vehicle development projects, which include planned logistics routes and the emissions from those are included in the price on CO2.

“The cost per ton of carbon is a global number that we are using for all kinds of sourcing,” says Enochsson. “In the material we are purchasing the biggest [carbon cost] is in the material itself and in the processing of the materials. Then there is CO2 in the actual transport. Here it is a discussion with our suppliers on how we can, over time, reduce the CO2 foot-print in the transport.”

The calculation of the cost per ton of carbon of each vehicle very much depends on the size of the vehicle and the battery installed. With regard to the logistics involved per unit, each car made by Volvo in 2021 generated 1.46kg of CO2 related to the transport used for both inbound parts shipments and outbound final delivery of the vehicle.

EVs currently more carbon intense than ICE

In its use phase of the vehicle, an XC40 powered by an internal combustion engine (ICE) produces 58 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (CO2e), while the battery EV version produces be-tween 27–54 tonnes CO2e depending on the different electricity mixes.

However, while the use phase of a XC40 Recharge EV has less of a carbon impact than its ICE predecessor, when considering the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions produced from the materials production and refining phase, including the battery pack, the EV accounts for 70% more carbon emissions than the ICE version. That is because the production of the lithium-ion battery has a large carbon footprint and accounts for between 10-30% of the total output depending on the electricity mix in the use phase.

This emphasises the need to localise battery production and find logistics efficiencies to offset the carbon expenditure in the manufacture of lithium-ion batteries until both the battery and the materials they are composed off can be sourced closer to the point of assembly.

Pricing the difference

Volvo is capturing real-time data and has created a digital twin of its supply chain network to calculate and analyse the CO2 emissions and analyse the network from different aspects to look for improvements.

There is significant variance in pricing when it comes to battery materials. Enochsson points to the example of nickel.

“There is huge difference in price when you compare the location from where you source the nickel, as well as how it is extracted and processed,” she says. “One ton of nickel from one location can have a CO2 impact that is 20 times that of a ton of nickel sourced from another location?”

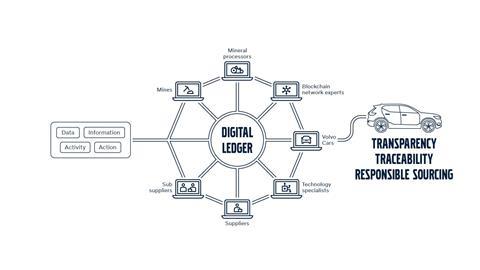

That difference is something Volvo is looking for when it uses the blockchain technology to trace battery materials, including nickel, cobalt and lithium. In 2020 Volvo Cars invested an undisclosed sum in blockchain technology provider Circulor to provide visibility into its battery supply chain and Circulor’s blockchain application is used throughout Volvo’s battery supply chain.

The company is now also using that blockchain technology to track the CO2 impact of those minerals both in terms of mining and processing, and from the transport of them to battery cell production site.

“We see exactly how the parts and materials that are going into the car

are being shipped and by that you understand the footprint of the transport,” she says.

There is no doubt that Volvo’s supply chain resilience will be tested by the next unforeseen disruption but the carmaker is also refining its supply chain analytics and using AI to forecast potential disruption from a wealth of data sources that show where a particular route may be blocked or where there is a bigger disruptive event in any global region.

With more vertical integration and greater end-to-end visibility on the supply of parts and materials, and with an emphasis on localised, sustainable and ethical sourcing and transport, Volvo is putting in place a more resilient supply chain to bolster its plans for 100% battery EV production by 2030.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet