The European automotive market is at an inflection point. Lower vehicle volumes post-pandemic, a shift from net exports to net imports and the growing influence of Chinese manufacturers are fundamentally changing the region’s logistics dynamics. Meanwhile, tariffs and localisation efforts are altering trade flows. As automakers and logistics providers adapt, the success of their strategies will determine who thrives in this new era of European automotive supply chains.

For decades, Europe has been an automotive export powerhouse, led by Germany. However, a fundamental shift is underway: Europe is on track to become a net importer of vehicles, driven largely by rising shipments from China and other Asian markets.

Market analysts describe this shift as a “great divergence,” signalling a departure from the free-trade consensus that once defined the global economy. Instead, the market is becoming more fragmented and protectionist. Since 2019, Europe has faced disruptions from Covid-19, supply chain challenges and geopolitical tensions that continue to reshape vehicle production and sales. The European Union (EU), once a strong advocate for free trade and open markets, is now implementing tariffs aimed at protecting its domestic industry from growing competition, particularly from Chinese electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers.

Mark Fulthorpe, executive director of light vehicle production at S&P Global Mobility, emphasises that this transition marks a significant departure from historical trends. Speaking at ECG’s 2024 annual conference, he noted: “For a long time, Europe has been an exporter of vehicles, shipping cars to China and North America. But that trade to China has been declining as Chinese OEMs ramp up domestic production.”

Exports to the US are also under pressure amid ongoing trade disruptions, with uncertainty surrounding potential tariffs on European cars. The US government is considering imposing duties on European-built vehicles – and potentially those from the UK – a move that could further strain automakers already navigating instability in transatlantic trade. When asked about the timeline for announcing tariffs on the EU, president Trump said: “I wouldn’t say there’s a timeline, but it’s going to be pretty soon.”

Following Trump’s comments, European stock markets reacted swiftly, with major indices falling back. Shares in some of the continent’s largest carmakers also slumped as concerns over potential import duties to the US added to market uncertainty.

Adding to the tension, Trump has also ordered a 25% import tax on all steel and aluminium entering the US, set to take effect on March 12, which will directly impact the EU. In response, the European Commission issued a statement: “We will not respond to broad announcements without details or written clarification. The EU sees no justification for the imposition of tariffs on its exports…

“The imposition of tariffs would be unlawful and economically counterproductive, especially given the deeply integrated production chains the EU and US established through transatlantic trade and investment… Moreover, tariffs heighten economic uncertainty and disrupt the efficiency and integration of global markets.”

At the same time, Europe is seeing an influx of vehicles from China, reversing traditional supply chain flows. Chinese automakers such as BYD and Great Wall Motors are expanding their European presence through direct exports and localised production in countries like Hungary and Turkey. They are focusing on low-cost, well-equipped EVs, including plug-in hybrids and battery electric vehicles (BEVs), to appeal to budget-conscious consumers. Leveraging technological advancements and efficient production methods, Chinese OEMs are positioning themselves in Europe’s EV sector. Their competitively priced vehicles are particularly attractive in regions such as Eastern Europe, South Asia and South America, where affordability is key to market entry.

This transition, however, is not just about market share but also logistics flows. As Fulthorpe pointed out: “Production levels have actually been boosted by a couple of effects. The first one was rebuilding inventory stocks, and the second one was satisfying that pent-up demand which had developed during Covid.”

With inventories now overstocked and demand softening, many Western automakers are reassessing their global production and export strategies.

Chinese OEMs drive market competition

Chinese automakers have made rapid inroads into the European market, particularly in the EV segment. In 2024, Chinese brands accounted for approximately 10% of Europe’s BEV sales, according to Schmidt Automotive Research, with that figure expected to rise as more production shifts to European facilities.

However, the growth of Chinese OEMs in Europe’s BEV market is unfolding within a highly competitive landscape, according to European automotive analyst, Matthias Schmidt of Schmidt Automotive Research.

He explains: “While their total volumes are expected to increase, the broader market dynamics – driven by regulatory changes encouraging more established Western automakers to expand their BEV offerings – mean these volume gains will not necessarily translate into a proportional rise in market share.”

Schmidt further notes: “Industry projections suggest Chinese OEMs will peak at a 12% share of the West European BEV market in 2027, coinciding with the full ramp-up of BYD’s Hungarian production facility.”

BYD is set to double its registered units in Europe in 2025 as it ramps up local production in Hungary. Schmidt says: “BYD is bringing its third long-term charter vessel online, increasing annual shipping capacity from China to Europe to around 100,000 units in 2025. But local production in Hungary will allow them to navigate tariffs and scale up their European presence.”

This move reflects a broader strategy by Chinese OEMs to establish European production hubs and better compete with local manufacturers.

Other Chinese brands are following suit too. Geely’s Polestar plans to begin producing a compact SUV in Europe by 2027, potentially leveraging Volvo’s facilities in Belgium. Chery has taken over Nissan’s plant in Spain but has opted to produce only internal combustion and hybrid vehicles there, avoiding regulatory complexities over subsidies. Meanwhile, Turkey is emerging as a key production hub for Chinese manufacturers seeking to leverage its customs union status with the EU. Agian, Chery is increasing vehicle shipments from China to Turkey, supported by DP World operations at the Yarímca container terminal.

As more Chinese OEMs establish production hubs in Europe, the logistics industry must adapt. The reduction in long-haul imports from China will increase intra-European distribution demands, particularly for finished vehicle transport and spare parts logistics.

Tariff pressures and strategic responses

The EU’s decision to impose tariffs on Chinese BEVs – ranging from 7.8% for Tesla to 35.3% for non-compliant Chinese OEMs – is reshaping trade strategies. These tariffs, which add to the existing 10% import duty, took effect on October 30, 2024, and will last for five years unless reviewed earlier.

Chinese automakers are already adjusting. As Schmidt explains: “Half of the Chinese brand vehicles arriving in Western Europe are hybrids or internal combustion, which means they bypass the additional tariffs. Chinese OEMs like MG are already increasing their hybrid portfolio in response to the new trade landscape.”

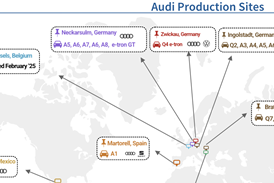

Meanwhile, European automakers are making strategic adjustments. BMW is repatriating production of the iX3 from China to Hungary, while Tesla may shift Model 3 production to Germany if tariffs persist.

For logistics providers, this means adapting to new vehicle flow patterns, including increased intra-European movements as both Chinese and Western brands opt for localised production.

However, tariffs pose challenges for European OEMs in China as well. Western brands are losing market share to domestic competitors, with Chinese automakers accelerating vehicle development at a pace that surpasses many foreign brands. Fulthorpe noted that some automakers, such as Ford, are repurposing Chinese factories as export hubs rather than focusing on local sales, while others, such as Stellantis and Mitsubishi, are scaling back their China operations entirely. This shift signals a broader realignment of global automotive production.

Port congestion, capacity constraints and distribution adjustments

European port operations are under increasing pressure due to the rise in vehicle imports, particularly from China, exacerbating congestion and capacity constraints at key hubs like Antwerp-Bruges. This growth, also driven by the expanding EV market, has highlighted the need for enhanced infrastructure and more efficient vehicle handling systems.

In response, ports across Europe are adjusting operations to accommodate shifting trade flows. Barcelona, for instance, has doubled its containerised car imports in 2024, with a significant increase in Chinese vehicle arrivals. The port’s use of containers for finished vehicle transport provides a flexible alternative to traditional roll-on/roll-off shipping, particularly amid car carrier capacity shortages.

Elsewhere, Mosolf is restructuring its port operations to meet rising demand, while ABP is investing in finished vehicle logistics services at Stallingborough.

The surge in vehicle imports has also accelerated a shift toward multimodal transport solutions, integrating sea, rail and road logistics. The expansion of China-Europe rail routes, such as the CEX container service, offers an alternative to congested ports and provides a more sustainable option for vehicle transport.

The “great divergence”

Europe’s automotive industry is at a turning point. The sector is transitioning from an era of global integration to one of regionalisation and protectionism, driven by the competitive expansion of Chinese OEMs and shifting geopolitical landscapes. For Western automakers, the challenge is to adapt while maintaining a foothold in China’s evolving market. Logistics providers and manufacturers must embrace flexible, region-specific strategies to navigate this complex new era.

The “great divergence” presents both opportunities and challenges for Europe’s automotive industry. As Chinese OEMs strengthen their foothold in Europe, European manufacturers will need to recalibrate supply chains, adjust logistics strategies and focus on resilience and regionalisation over global integration.

Key takeaways:

- Europe is transitioning from a net vehicle exporter to a net importer, requiring new logistics approaches.

- Chinese OEMs are localising production in Europe, reshaping supply chain demands.

- Tariffs are altering trade strategies, pushing both Western and Chinese automakers to adapt.

- Logistics providers must expand port, rail and intra-European distribution networks to meet evolving demands.

Topics

- Analysis

- BMW

- Chery

- Data Analysis & Forecasting

- DP World

- Editor's pick

- Electric Vehicles

- Europe

- EV & Battery Production

- Finished Vehicle Logistics

- Fleet & Route Optimisation

- Ford

- Geely

- Inventory management

- Logistics service provider

- Mitsubishi

- Nearshoring

- Nearshoring Strategies

- News and Features

- Nissan

- OEMs

- Ports and processors

- Shipping

- Stellantis

- Supply Chain Planning

- Sustainability

- Sustainable Supply Chain Design

- Tesla

- Trade & Customs

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet