Audi’s head of procurement strategy, Marco Philippi, is pushing its supply chain towards meeting ethical and environmental targets, while managing structural changes for global purchasing in a new world order

Procurement for global carmakers has rarely been so complex: shortages of critical components and capacity; runaway inflation across commodities and energy; financial and operational risks at suppliers; and geopolitical tensions that could redraw the industry’s sourcing and trade maps.

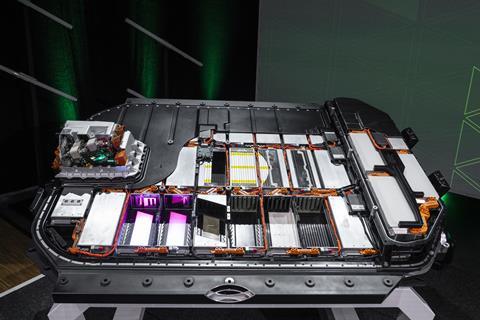

Those headwinds come alongside managing long-term structural changes in automotive products and manufacturing, including the ramp up of electric battery and vehicle production, and the transition to decarbonised, more sustainable supply chains.

OEMs in Europe, and especially in its manufacturing centre Germany, face even sharper edges in the supply chain. Limits to gas and oil supply from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for example, are leading to price spikes and could force energy rationing across industry in central and eastern Europe. Covid lockdowns and logistics issues are disrupting supply and trade with China, where German OEMs have such important sourcing, production and sales footprints.

Another hurdle that is less existential, but nevertheless complex is a law set to come into effect in Germany from January 1, 2023, the Supply Chain Due Diligence Act – a regulatory mouthful in German as the Lieferkettensorgfaltspflichtengesetz. It requires stricter reporting and monitoring of labour, social and ethical conditions across companies’ global suppliers and sub-suppliers. The new law, along with other similar regulations across the EU, will put more emphasis on standards and transparency in the supply chain, especially as production and sourcing of lithium-ion batteries grow.

For Audi, its 14,000 direct suppliers and the five global manufacturing plants that it directly operates (Audi-brand vehicles are built in 16 plants in 10 countries across Volkswagen Group and joint venture plants), these challenges are as unwieldy as for other OEMs. However, the premium carmaker is ahead of the curve in purchasing processes and supplier management, which will help in meeting regulatory requirements and reducing emissions. Since 2018, it has applied ratings and audits in sustainability across its suppliers, offering training to those struggling to meet targets and disqualifying those which cannot meet the necessary ‘S-Rating’. Alongside all Volkswagen Group brands, Audi has implemented a global code of conduct for business partners, adapting requirements to address labour practices in areas such as cobalt and lithium mining for batteries, for example. It has even started to use artificial intelligence to monitor warning signs that suppliers may be falling foul of standards.

And in procurement, Audi has also worked in close collaboration across departments and suppliers to systematically apply CO2 reduction and environmental targets, with a strong track record in cutting emissions through technology innovations and closed loops.

For Marco Philippi, head of procurement strategy at Audi since 2019, ongoing supply and geopolitical crises are only accelerating his team’s targets and the business case for initiatives in sustainable material sourcing as well in reducing supply risk – an important investment in supply chain resilience and efficiency.

“From a strategic procurement point of view, we are speeding things up. The business case for many topics in sustainability is becoming clearer,” he says.

Philippi, who is responsible for central purchasing functions, sustainability and innovation at Audi, and previously worked in procurement strategy across Volkswagen Group, is not naïve about how hard it will be to pivot Audi’s sourcing and supply chain towards lower emissions and more recycled content. The carmaker measures several decisive factors on equal footing with sustainability: security of supply, logistics performance, technological quality and innovation, quality of components and supplier capability and of course costs, including exchange rates, inflation and customs duties.

Meanwhile, gaining full transparency of risk in the supply chain – whether in operations or labour practices – is nearly impossible, especially as some components require as many as nine tiers between raw material and final delivery to Audi.

However, it is precisely this supply chain scale that gives Philippi confidence in the company’s capacity to promote change.

“If we have our suppliers enforce our sustainability ratings to their suppliers, we’re talking about 14,000 direct partners in 60 countries multiplied by ‘N’ acting on it. When we look across the group, it is 60,000 suppliers.

“This is a power we are aware of. We want to use our supply chain as a force for good.”

Audi’s pillars of supply chain sustainability

Audi’s procurement strategy is split across three main pillars covering social aspects, environment and innovation. Technology is a key enabler of these areas, and Marco Philippi also points to new partnerships both within Audi departments – including design, purchasing, manufacturing and logistics – with the wider Volkswagen Group, as well as with suppliers.

-

People. As the first pillar, Audi aims is to ensure that all ethical, social and labour considerations are met in sourcing and procurement. That means meeting requirements for Germany’s Supply Chain Due Diligence Law and other regulations, as well as monitoring and updating the Volkswagen Group’s code of conduct, including for business partners.

-

Environment. A second pillar focuses on reducing CO2 and material waste, such as water. It also means embedding environmental targets into purchasing KPIs alongside factors like quality and cost and pursuing circular economy principles to increase recycling and protect against future material shortages and price rises.

-

Innovation. Protecting people and environment depends on innovation and technology. For example, Audi’s procurement team uses AI to detect early warning signs in news and social media that a supplier or sub-supplier might not meet standards. It also partners with key suppliers to pilot innovations in closed material loops, most recently for glass.

Being honest about visibility

Supply chain transparency is one of the most significant challenges for procurement across industries, from textiles to energy, and the German supply chain law only reinforces that. Philippi points to multiple levels of raw materials, processing and production for the automotive sector. It is especially difficult in the growing battery supply chain, where some materials are mined in countries with poor oversight, such as cobalt in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The battery supply chain is both so nascent and complex that Philippi says that it can take months to screen all the supply and production areas, which leaves considerable room for fluctuation and gaps.

“Having that under complete control is currently impossible.,” he says. “But we are working on it, and this is where you need horizontal and vertical partnerships.”

That is also a key reason why Volkswagen has joined the Certification of Raw Materials project, or CERA, which has developed a standard for certifying mines. In 2021, it was piloted and tested on site at a mine operator identified in the Volkswagen Group’s cobalt supply chain.

An important approach for Audi and the group’s procurement is to measure everything in relation to its global code of conduct for business partners. Although it is not prescriptive for every material, it is updated with specific detail in key areas. “If you talk about battery raw materials, for example, we have a specific set of specifications that we require and for disclosure of certain information that will put us in a position to act,” says Philippi.

The Volkswagen Group currently tracks 16 critical materials to monitor human rights considerations, which certain brands in the group taking the lead on key areas, such Audi for aluminium. That leads to new specifications for suppliers. And while suppliers who don’t meet the right criteria cannot work with Audi, the carmaker takes an engaged approach to help suppliers improve operations and scores. In 2020, Audi developed online training courses to educate its suppliers about the requirements and show possible ways for implementation. More than 1,000 suppliers participated in these trainings in 2021.

Audi also partners with manufacturers beyond the group. As part of the Drive Sustainability initiative, for example, it has worked with OEMs to rate raw materials across different risk categories, including child labour and environmental concerns. It has been a part of the Global Battery Alliance since 2017, with the aim of establishing a responsible battery value chain. In October 2021, Audi was also one of the founding members of the Responsible Supply Chain Initiative within the German automotive manufacturers’ association, the VDA, which has established a standardised assessment of production sites across the global supply chain.

Setting standards across its code of conduct and in industry partnerships are partly why Philippi feels Audi is well prepared for the supply chain due diligence law. However, he hopes that common standards will eventually prevail across the industry instead of a regulatory patchwork. The EU is set to follow the German example in supply chain compliance requirements, and it will be challenging if countries and regions take different approaches, he admits. Audi wants to work in close alignment with other companies ahead of new regulations. Earlier this year, for example, Volkswagen Group joined consortium of companies with funding from the German government aimed at forming a Battery Passport that contains digital information on material origins.

“We want to allocate our efforts to develop and align on joint international standards, as this will help us most,” he says.

Putting supply chain risks on the radar

Whilst these initiatives are critical steps, Philippi admits that the scale of the automotive supply chain makes it difficult to monitor everything. Using advanced technology is a must. Whilst several years ago many in the industry thought blockchain might be the answer – with Audi among OEMs to trial solutions – there is still no silver bullet solution.

Since October 2020, however, together with Porsche and the Volkswagen brand, Audi has been using an AI-driven monitoring solution from Austrian startup Prewave. The system acts on a radar principle, scanning supplier information from publicly available news and social media and using an algorithm to detect warnings that a company might be in violation of the group’s code of conduct, notably around human rights, corruption or sustainability practices. The technology has helped the companies discover issues months in advance.

“An average, we found that we are able to improve and act against issues with a huge time benefit than without the tool,” says Philippi. “We are now able to stop or prevent an issue two months earlier, which is really worth it.”

Speeding up progress in sustainability

Audi’s supplier reporting and monitoring, along with targeting potential risks, have parallels in how it has reduced emissions, too. Audi has identified key areas where companies can improve environmental practices, for example, including a ‘hot spot’ approach to reduce emissions. It focuses on the materials with the highest carbon footprint, notably steel, aluminium, plastics, glass and EV batteries. “We then look into the parts that contain these materials and for partners with which we can work to bring this down,” says Philippi.

Working with suppliers, Audi has saved around 480,000 tonnes of CO2 across the supply chain 2021 alone, he says.

Achieving these savings also means higher costs for certain materials compared to legacy components, admits Philippi. That has been built into Audi’s procurement matrix, with CO2 and material reuse increasingly a ‘value’ to consider.

“It’s no longer just a matter of idealism. We have specific targets on recycled materials and specific targets on CO2 emissions, including across the value chain,” Philippi says. “That has made these targets part of corporate reality, and something we have to deliver on such as we would other specifications around cost or quality.”

That does not mean, however, that emissions targets can outpace Audi’s ability to invest sustainability, or to squeeze suppliers. “If it’s an issue around ethics or human rights, then it’s a black-and-white decision. But for many materials and processes, we have a responsibility not to go too fast,” he says. “We need to have a transformative dialogue with suppliers, adapting our goals year by year to make sure we don’t lose anyone.

Closing the loop

And yet, there are critical areas to speed up innovation and investment, too, which current commodity shortages and costs underline. Philippi envisions that these shortages will worsen, especially as more OEMs strive to use recycled materials in cars and in batteries. “If you add up all the targets for recycled materials that OEMs are planning to use, there is a huge gap, bottom line. There will be a run on certain materials in the next years.”

Philippi points to two ways for OEMs to avoid these shortfalls: by working with partners to procure materials at a certain price over a long period; and by creating more closed loop material cycles to create and use more recycled materials to save primary resources wherever it is technically and economically feasible.

Audi is doing both, but Philippi believes that creating more circular loops in the supply chain across a company will have the most strategic influence on the supply chain over the next decade. Over the past three years, Philippi’s team has worked closely with Audi’s suppliers to develop and pilot innovative new closed loops. In 2017, it implemented closed loops for aluminium in Neckarsulm, which has since been rolled out to other plants: Audi added the process in Ingolstadt in 2020 and at its Györ, Hungary plant in 2021. According to the company, the aluminium closed loops helped Audi save a total of 195,000 tonnes of CO2 in 2021, 30,000 more tonnes than in 2020.

The Volkswagen Group factory in Bratislava, Slovakia – which currently builds the Audi Q7 and Q8 – announced this past July that it would also join the aluminium closed loop network.

Audi is exploring further opportunities in circular supply chains: in 2021 it demonstrated the possibilities of chemical recycling through a pilot using a pyrolysis process to recycle mixed automotive plastic waste; and this year, it is piloting the use of recycled glass.

Such closed cycle approaches address Audi’s strategic aims in procurement: they improve transparency of origin; they help guarantee price and availability; and they reduce emissions. In the current climate, the business case for these approaches is becoming more compelling.

“We observe that the pilot projects we look at right now are becoming increasingly feasible financially, even without the sustainability and transparency benefits,” he says. “Less energy means lower costs, and by closing the cycle you are also closing the dependency risk on external energy supply.

“Our pilot research shows that there is also another positive effect on carbon emissions,” adds Philippi. “Recycling emits up to 30% less carbon dioxide compared with manufacturing new glass.”

Circular collaboration across departments

Building more circular, resilient supply chains takes a willingness to invest, but also more integrated ways of working across departments in development and production cycles. It is one thing for the design team to introduce a new recycled material in the concept phase of a vehicle; it is another for it to take it into serial production.

The times when design, engineering and purchasing teams tended to work in silos when it came to supply chain innovation are over, admits Philippi. In the past two years, the procurement team has worked in close alignment across departments to maintain transparency, sustainability and CO2 targets, which has helped to turn visions into reality.

“It would be too much to say that we have a serial process firmly in place, but over the last years we have put all the functions together,” he says. “Of course, sometimes you have ideas from design that don’t work in production or testing, but we are aligned on our targets. The way you get a sustainable idea into a project is to have everyone along the value chain working on it.”

Shortages in materials and logistics capacity are also reconfiguring sourcing considerations, including trade terms, inventory, transport and delivery risk. For example, logistics teams work with purchasing in the development of each product, according to Dieter Braun, head of supply chain at Audi.

“We are strongly interacting with the purchasing department to think about sourcing and localisation,” Braun said during the Automotive Logistics and Supply Chain Europe conference in May, adding that it was an important consideration for cost-competitive sourcing and the reduction of supply chain emissions.

Purchasing in a new world order

Philippi suggests that manufacturers will have to adapt its purchasing considerations more frequently to keep pace with changes in material technology as well as geopolitical tensions, from Russia-Ukraine to China. He suggests that global paradigms may be shifting, with the pandemic, logistical issues, trade tensions and war disrupting assumptions about sourcing globally.

“It would be great if we could rely on the global market we were used to, but I think it will be hard,” he says. “You have to prepare for that. Different regions will have different demands, which are valid for customers, as well as governmental regulations in terms of technical specifications and reporting, which of course impacts procurement processes.”

For the supply chain, it’s a huge shift following decades of “never ending globalisation”, he adds, and it must be considered already in sourcing decisions made today, or else the company will face barriers in the years ahead.

On the macrolevel, these changes are hard to predict, but one thing is less so: Audi is ready to invest in its purchasing when it comes to sustainability and improving stability across the supply chain. “The challenges of the past two years – Covid, semiconductor shortages, the war in Ukraine – show us that it is worth paying the price for resiliency in some material groups.”

Marco Philippi, born in Munich in 1977, joined Audi as head of procurement strategy in October 2019, responsible for managing the strategy and central functions of the division, for sustainability in the supply chain and for innovation management with suppliers. Before that he held a dual-function position for the newly created ‘procurement strategy’ area across the Volkswagen Group and Volkswagen brand from 2017-2019. He began his career at Volkswagen Consulting in 2004, before moving into corporate strategy and later procurement across the group. He studied international business at Reutlingen University, where he graduated with an MBA.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet