Last week’s BVL Congress in Berlin celebrated a German logistics market that is on pace for another record year in 2012, buoyed largely by strong exports and manufacturing, including automotive. The leader of the opposition Social Democratic party proclaimed the country a “logistics superpower”. But with further slowdowns in global markets potentially on the horizon, and the Eurozone crisis standing at the gates of the German economy, there are clear risks to the industry’s health.

Furthermore, while Germany’s transport infrastructure was credited as a competitive advantage for the country’s supply chain efficiency, there was concern voiced that investment in infrastructure is currently insufficient, with the BVL, Germany’s membership network of logistics and supply chain experts, calling for an outright doubling in current investment levels over the next 15 years.

After growing 6% in 2011 to reach an all time high of €223 billion ($290 billion), the German logistics market is on pace to grow another 3% this year to €228 billion, according to Dr Raimund Klinkner, president of BVL International, who moderated the conference. Employment is also estimated to be up by around 100,000 workers to 2.8m.

In a nod to the importance of logistics and manufacturing to the German economy, the BVL – a non-profit, federally funded logistics association – saw a number of high-ranking politicians in attendance. Frank-Walter Steinmeier, chairman of the parliamentary party of the Social Democrats in the German Bundestag, the current opposition leader and a former foreign minister and vice-chancellor, told delegates that the strength of Germany was as much about logistics as it was the more prominent standard bearers, such as cars, chemicals and engineering.

“I have a different image of the German economy from when I was foreign minister. I remember seeing DHL and Schenker logos in every country that I went,” he said. “Only a few people know that Germany has become a logistics superpower.”

Germany’s global automotive logistics links

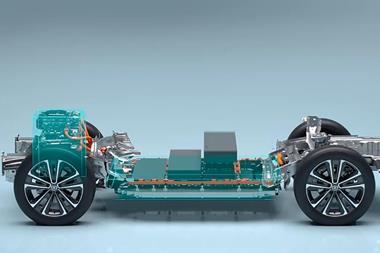

The global growth of the German automotive industry obviously indicates the rise of Germany’s logistics and supply chain powerhouse. Matthias Wissmann, president of the German Association of the Automotive Industry (VDA), and a former Transport Minister, pointed out that Germany was not only the sole European country to increase its automotive production in the past two decades – with passenger car levels on pace to remain stable at a record 5.5m units this year – but its brands now also produce 8.5m units outside of Germany.

Even with more ‘German’ cars produced outside of Germany than in it, a large share of the “value creation” of these vehicles remains in Germany, with small-and-medium sized suppliers – the famous German Mittelstand – playing a critical role in exports. Wissmann pointed out that Germany has twice as many such companies that export than does France, for example.

The conference had no shortage of evidence in this direction. One example came from Dinora Guerreiro, material handling and transport manager for Volkswagen Autoeuropa in Portugal. She revealed that out of the 678 suppliers providing material for the four models built at the plant, 478 were from Germany and Central Europe. Around 175 suppliers were based in Spain or Portugal, and just 14 in France. VW Autoeuropa makes uses of consolidation centres in Kornwestheim and Baunatal in Germany to arrange truck transport to Portugal, while the company has also recently shifted 10% of its land transport from Germany to long-distance rail.

Automotive’s export focus, in both material and vehicles, therefore puts more emphasis on the quality of logistics across all modes of transport. Peter Ramsauer, Germany’s Transport Minister (pictured), pointed to the use of the railways to connect BMW’s plant in Leipzig to China overland via Russia, which moves material between sites in 23 days, about half the length of a ship. “I recently met with Russian ministers to discuss how to cut that time further to 12 days,” he said.

The economic and operational importance of logistics providers for the German automotive industry was also emphasised. “The automotive industry needs a highly qualified logistics chain, as 70% of the costs for building a car comes from suppliers,” said Wissmann. “The organisation of transport is decisive; [logistics providers] are the oil in the gears of [the automotive] supply chain.”

The threat of infrastructure decline

But Germany is facing a number of risks that could impact its logistics prowess and economic growth. Dr Klinkner pointed out that German GDP growth is now forecasted at less than 1% for both 2012 and 2013, while the BVL’s logistics indicators are at their lowest level in more than two years and point to declining outlooks.

The wave of decline in the European market for new vehicle sales appears to have also hit Germany, with sales declining 11% last month. While production and exports have been relatively stable, German-based producers are also facing severe headwinds, with Opel mulling the first German car plant closure since the Second World War.

But aside from the risks in the global economy, speakers pointed to the further economic and competitive risks that stem from a failure to maintain and upgrade German infrastructure. While normally considered one of the country’s strong points, Germany slipped to 4th place in the 2012 World Bank’s Logistics Performance Index, after coming top in 2010.

Klinkner pointed to recent studies that suggest Germany might be underinvesting in infrastructure by as much as €7 billion per year. He warned that at this rate Germany would not be able to keep up with rising freight and passenger levels. “Traffic is predicted to grow by 74% in freight and 18% in passengers by 2025. At that rate, we would require a clear doubling in infrastructure investment at current levels,” said Klinkner, which the BVL officially supports.

The German annual infrastructure budget, which is currently around €12 billion, has already seen about €1 billion increased last year, according to the Transport Minister Ramsauer. “We are now negotiating in Parliament to unblock another €1 billion, which will allow us to move on with current construction projects,” he said.

But Ramsauer acknowledged that Germany needed more financing across all modes of transport, in particular more sustainable channels such as inland waterways. He suggested that ‘public-private partnerships’ (PPP) would continue to be a helpful tool for unlocking more financing.

“PPP can help launch projects that would otherwise be last on the priority list,” he said, pointed to certain river port projects as an example. He acknowledged criticism that such partnerships meant that government could lose money on revenue generated from such projects over the long term, but maintained that they were the best way to generate more investment in the face of shrinking public budgets and austerity.

The VDA’s Weissmann said that infrastructure investment would be vital to Germany’s automotive and economic success. “Without infrastructure investment, we will not have economic power,” he said. However, he was encouraged by the government’s move to expand its budget. “If this €2 billion were approved between last year and this year’s budget, it would be a bit step in the right direction,” he said.

Steinmeier, who will lead his party against the Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democrats and current coalition government in a general election in 2013, was more critical. Calling current government policy inadequate, he made it clear that, in some ways, logistics and infrastructure would fall within the political battle lines for next year. He warned that Germany risked losing its ranking as an export champion and growing logistics superpower without investment across all transport modes.

“Our modal connections will be decisive as to whether Germany stays as the top exporter or slips to number two,” said Steinmeier.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)