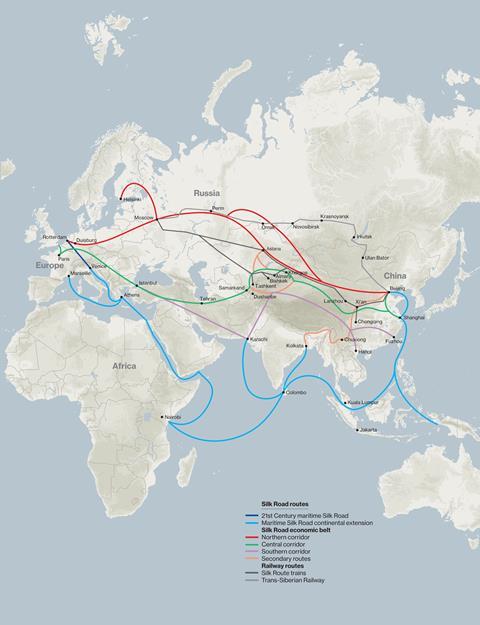

Carmakers have been looking for alternative routes to deliver finished vehicles and automotive parts between Europe and China since the latter invaded Ukraine. Prior to that, Russia was the preferred route for shipping cargo between the two regions because of the lower costs and lower number of customs checkpoints.

In 2021, 68% of westbound traffic and 82% of eastbound traffic moving between China and the EU went through Russia. Now, however, several European carmakers have stopped shipping vehicles by rail to and from China with state-owned Russian Railways (RZD).

“Audi proactively suspended rail transports to and from China via Russia’s Trans-Siberian Railway immediately after the beginning of the Ukraine war,” said a spokesperson for Audi’s production and logistics operations, adding that the company has since switched to alternative routes.

“Since then, these vehicle and material transports have been handled by sea freight and truck via the southern route via Kazakhstan, Georgia and Romania. We are currently examining whether transport by rail via the southern route will also be a possible alternative in the near future,” said the spokesperson.

BMW Group also confirmed it had diverted some supplies on alternative routes to avoid using Russian territory, having previously used Silk Road and Trans-Siberian rail links for vehicle movements to China, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia, as well as for freight transports between Europe and China.

Porsche also said it stopped transit deliveries of finished vehicles from Europe to China through Russia, but did not provide further details.

Ocean to rail

Over the past few years, several carmakers have switched from ship to rail to lower their carbon emissions, as well as to pursue higher speed and schedule reliability, particularly as Covid-19 disrupted port operations in Asia.

In 2019, RZD said that the rising volumes of finished vehicles it was taking by train between Europe and Asia showed that the Chinese Belt and Road initiative had made rail a competitive alternative to ocean shipments. It takes only 15 days to deliver finished vehicles from Germany to China, as compared to 60 days by ocean vessel.

Olga Stepanova, sales director of the train operator’s logistics subsidiary RZD Logistics, disclosed that there were three corridors for finished vehicle shipments from Europe to China via Russia: through Mongolia, through Kazakhstan or via the Zabaikalsk-Manchuria border crossing. Stepanova added that trains were loaded in both directions, delivering premium finished vehicles from Europe to China and mass-market models from China to Europe.

Under contract with the Russian Railways, Mercedes-Benz began finished vehicle deliveries from Bremerhaven, Germany, to Chongqing, China in 2018. Russian Railways also reported that Volvo and some other carmakers were interested in moving cargo via the Silk Road.

BMW originally had plans to transport 16,000 finished vehicles through the new Silk Road from Europe to China. However, the actual volumes did not reach that figure.

“We only started Silk Road deliveries in 2021, so the initial volume was lower,” said BMW’s spokesperson.

Supplies of complete and semi knockdown kits (CKDs/SKDs) and components by rail from Europe to China were also on the rise in recent years, such as those moved by Audi.

“We do not transport completely finished vehicles to China,” said the carmaker’s spokesperson. “Depending on the model and location, the vehicles are dismantled to varying degrees for transport and rebuilt at their destination for delivery,” he said.

Existing alternatives

Currently, more than 90% of cargo between China and Europe is transported by sea, bypassing Eurasia through the Indian Ocean and the Suez Canal, according to Natalya Churkina, an analyst at the Russian Institute for Comprehensive Strategic Studies. In the spring of 2022, China launched a rail and ocean route bypassing Russia through Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia to Romania, she added.

Georgy Svirin, an analyst at the Russian Finmir marketplace, confirmed there are existing direct trains from China to Germany through Kazakhstan and the Caspian Sea. He also said that traffic on that route was expected to rise in the coming years but that the infrastructure required significant investment and there were geopolitical risks.

“The development of large-scale infrastructure [for a] transport route that unites several countries is jeopardised every time because of political instability in the regions where the new Silk Road runs,” Svirin said.

Geopolitical risks

Contrary to Russian Railway’s view of rail as a competitive alternative to ocean shipments, a spokesperson for the Russian automotive industry, who wished not to be named, told Automotive Logistics that the Belt and Road Initiative has so far not turned into a realistic alternative to ocean transport, and constant geopolitical risks were one of the reasons to blame.

“Volvo pulled out from delivering finished vehicles by rail [from Europe to China] even before the war,” said the Russian automotive source. “[The carmaker] cited poorly developed infrastructure, low-quality services along the way and high costs that jumped during the Covid-19 pandemic.”

The quality of services and logistics costs could be improved through investments, but foreign players are not ready to allocate money because of political risks. The source cited riots and fights in Kazakhstan in January of 2022 as an example of the turbulence typical of this part of the world and explained that the entire region has risks that discourage investors, though they said the Russian invasion of Ukraine put the problem on a completely different scale.

Tough terrain

Maxim Kuznetsov, founder of Russia’s Pivot to the East project, which is aimed at fostering closer ties with China, said that the transit of goods from China to the EU bypassing Russia is economically a controversial project. The alternative route through Turkmenistan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan and Georgia (Transport Corridor Europe-Caucasus-Asia – Traceca) has serious logistical hurdles because of a need for transhipment through the Caspian and Black Seas, complicating logistics and incurring additional costs.

“The complex terrain of Eurasia makes several routes difficult, so it’s premature to talk about [any significant] transit of goods from China to Europe bypassing Russia,” Kuznetsov said.

However, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route Association (Titra) recently reported that cargo shipments across central Asia and the Caucasus are expected to reach 3.2m metric tons in 2022, a sixfold increase over the previous year.

![Global[1]](https://d3n5uof8vony13.cloudfront.net/Pictures/web/a/d/s/global1_726550.svgz)

No comments yet